“The School of Athens” Raphael – Analyzing This Famous Artwork

The School of Athens by Raphael, produced from 1509 until 1511, is a famous Italian Renaissance fresco painting that was created to adorn the Vatican’s Apostolic Palace. The School of Athens painting is renowned for its realistic utilization of perspective projection. In this article, we will cover an in-depth The School of Athens analysis, as well as answer intriguing questions such as “What is Plato’s gesture in School of Athens, and what is meant by it?”. We will also discover why The School of Athens by Raphael is regarded as a painting that embodies the essence of the Italian Renaissance period.

Contents

The School of Athens by Raphael

The School of Athens painting was the last of three artworks produced for the Stanza della Segnatura, the room that Raphael decorated inside the Apostolic Palace. In The School of Athens analysis, we will answer questions such as “Why were the Greek god Apollo and the goddess Athena included in the School of Athens painting?” But before we get stuck into the details, we need to first start with the simpler questions, such as “Who painted The School of Athens?”

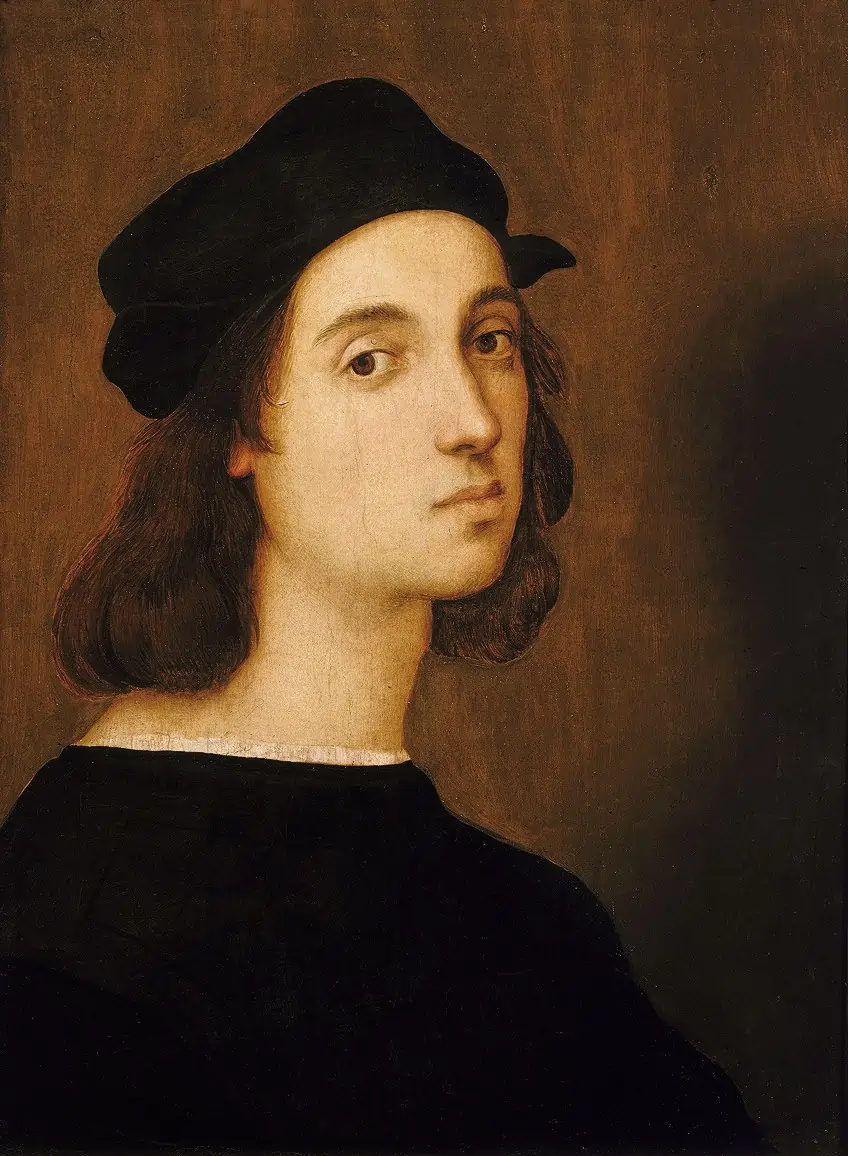

An Introduction to Raphael the Artist

| Nationality | Italian |

| Date of Birth | 6 April 1483 |

| Date of Death | 6 April 1520 |

| Place of Birth | Urbino, Italy |

Raphael blazed a meteor’s trail of art over the Italian High Renaissance in only 37 creative and energetic years. Raphael’s creations are the means through which his true passion for life revealed itself. His skill in communicating the Renaissance Humanistic era’s aesthetic concepts was considered strikingly new. Raphael’s artworks are recognized as masterworks in the same coveted category as those made by Michelangelo and Da Vinci.

Raphael’s tremendous aptitude as an artist, despite his relatively short lifespan, was the result of training that began when he was a child. From his childhood in his artist father’s workshop through his adult years as the director of one of the best studios of its kind, he positioned himself as one of the most productive painters of his time.

Raphael’s canvases were regarded as some of the finest representations of the age’s humanistic spirit, which sought to evaluate man’s worth in the world via creations of pure beauty. Raphael not only mastered High Renaissance artistic qualities such as perspective, perfect anatomical correctness, and authentic expression of emotion and clarity, but he also featured a distinct style known for its purity, brilliant palette, and simple organization.

Although Raphel is most known for his paintings, some of which can be seen in the Vatican Palace, the Raphael Rooms murals were his most ambitious effort. To put it in other words, he was a true Renaissance thinker. In comparison to one of his key opponents, Michelangelo, the artist was known for his genial attitude, vast popularity, and pleasant demeanor, as well as his tremendous admiration for ladies.

In terms of popularity and career possibilities, his social skills and pleasant disposition offered him an advantage over his colleagues at the time. Regardless of the path that contemporary art finally followed, Raphael is still respected for elevating the discipline of painting to the peak of technical success, which later generations would take as the standard to strive for. Titian, Albrecht Dürer, Rembrandt, Sir Joshua Reynolds, Velazquez, and Pierre-Auguste Renoir are among those who have paid respect to this most unique of painters in their own work.

Despite the increasing temporal gap that alludes to dull our awareness of the Renaissance era, Raphael has stayed persistently set in our minds from the early 16th century.

The School of Athens Analysis

| Date of Completion | 1511 |

| Medium | Fresco |

| Dimensions | 500 cm x 770 cm |

| Current Location | Apostolic Palace, Vatican City |

The School of Athens painting is one of four major paintings depicting diverse areas of knowledge on the wall surfaces of the Stanza (those on each side centrally broken by windows). Each topic is represented above by a distinct tondo depicting a beautiful female form reclining in the clouds. As a result, the figures shown on the walls below represent philosophy, poetry, faith, and justice.

The painting’s theme is about philosophers and their ideologies, or at least the philosophy of ancient Greece.

The prominent individuals in the scene appear to be Aristotle and Plato. Many of the thinkers represented, on the other hand, seek understanding of first causes. Many people existed before Aristotle and Plato, and only around one-third of them were Athenians. The construction has Roman characteristics, but the basic semi-circular arrangement with Plato and Aristotle at its center might be a reference to Pythagoras’ monad.

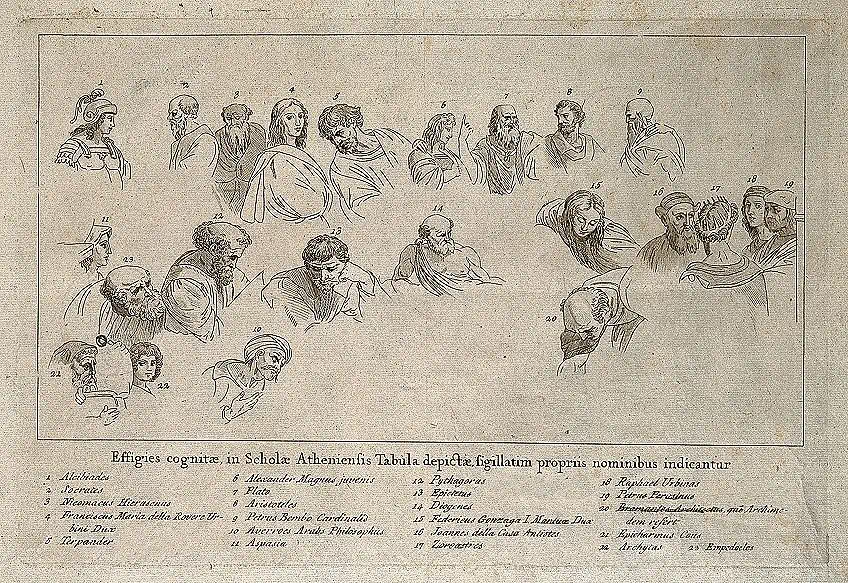

Critics have speculated that the picture depicts practically every important ancient Greek intellectual, although establishing who is shown is speculative because Raphael made no labels outside probable likenesses, and no historical texts explain the image. To make matters worse, Raphael had to construct an iconography structure to refer to numerous characters for whom there were no standard visual forms.

For instance, while Socrates’ image is easily recognized from Classical statues, one of the figures purported to be Epicurus is very different from his conventional representation. Other aspects of the painting, aside from the identities of the characters, have been widely interpreted, but few of these theories are universally recognized among experts. It is often assumed that Plato’s and Aristotle’s rhetorical gestures are forms of directing (to the skies and down to earth).

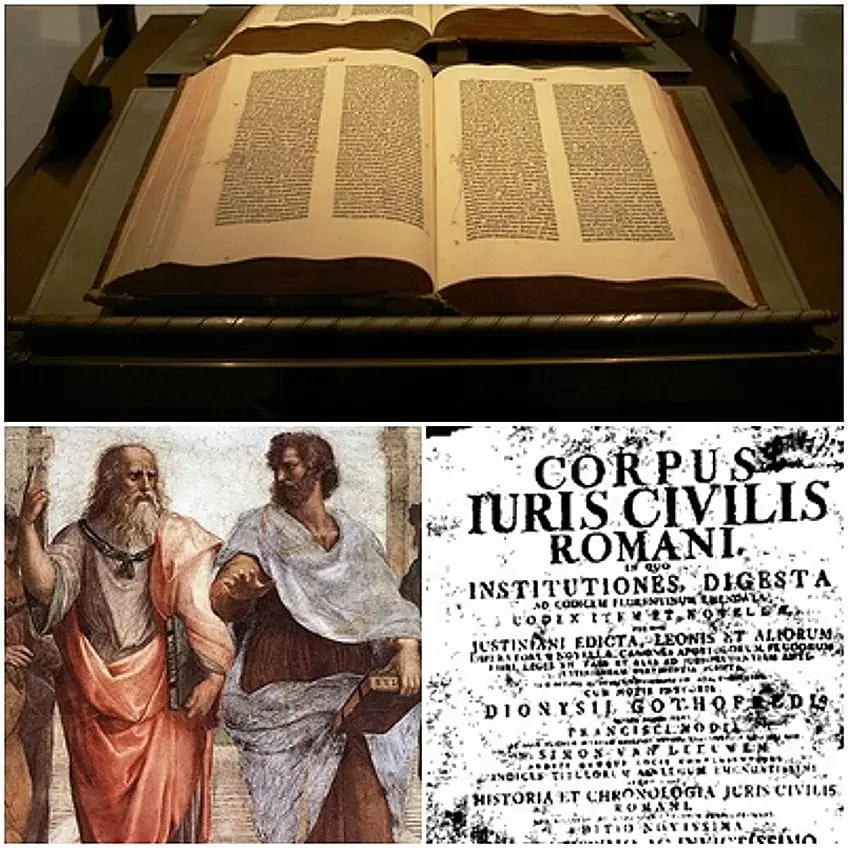

Plato’s Timaeus, on the other hand – the book Plato holds – was a complex account of dimension, time, and transformation, including the Earth, that led mathematical disciplines for almost a millennium. With his four-elements theory, Aristotle claimed that all change on Earth was caused by the motions of the sky. Aristotle is carrying his Ethics, which he claimed could be condensed to a mathematical discipline, in the artwork.

It is unknown how much the youthful Raphael understood about ancient philosophy, what assistance he might have received from persons like Bramante, and whether his benefactor, Pope Julius II, prescribed a comprehensive plan.

Nonetheless, the mural has in recent times been construed as an admonishment to philosophy and, in a greater sense, as a graphic display of the responsibilities of Love in uplifting people toward higher knowledge, which is largely consistent with modern hypotheses of Marsilio Ficino as well as other neo-Platonic theorists associated with Raphael.

Some historians, however, argue that interpreting the School of Athens by Raphael as an occult treatise is incorrect. In Raphael’s day, “the most essential factor was the artistic purpose, which portrayed a bodily or spiritual condition, and the name of the individual was a subject of indifference.”

Raphael’s skill then orchestrates a beautiful environment, concurrent with that of the spectators in the Stanza, in which a wide range of human figures, each conveying “mental moods by physical movements,” engage in a “polyphony” unlike anything seen before, in the ongoing discourse of Philosophy.

The Figures in The School of Athens Painting

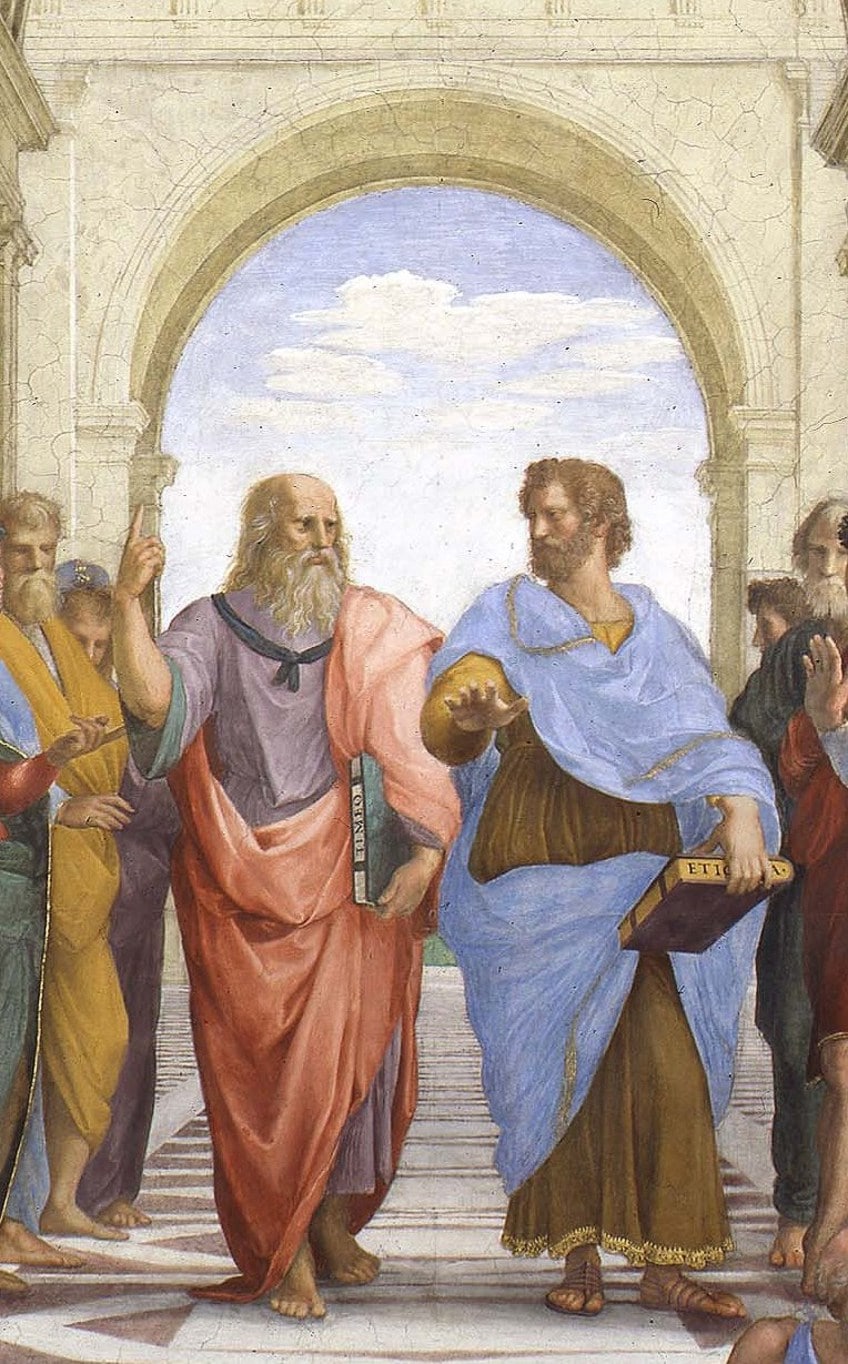

The two primary characters in the piece are placed exactly beneath the archway and in the mural’s vanishing spot, a compositional device used to bring the viewer’s attention to the most essential section of the artwork. Here, we find two men who essentially symbolize opposing philosophical schools: Aristotle and Plato. Plato, an old gentleman, stands to the left, gesturing to the sky. Aristotle, his disciple, stands behind him.

Aristotle extends his right arm straight out towards the observer in a masterful demonstration of foreshortening. The “true” universe, according to his ideology, is not the physical one, but rather a spiritual realm of thoughts populated with abstract notions and ideas. Plato defines the physical sphere as “the tangible, imperfect objects we see and engage with on a daily basis.”

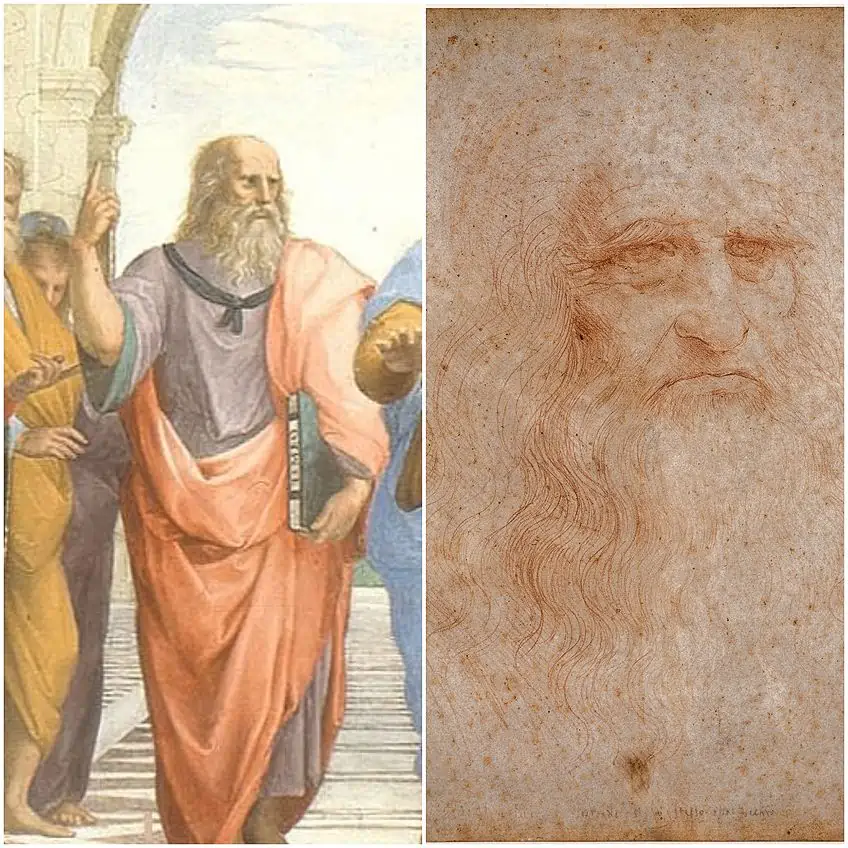

There are a few individuals who hypothesize that Raphael borrowed Leonardo da Vinci’s image for Plato because of parallels in his self-portrait.

Aristotle’s hand, on the other hand, is a visual symbol of his view that knowledge is gained by experience. Empiricism, as it is termed, speculates that humans must have real evidence to back up their views and is firmly rooted in the physical world. Scholars contend that the schism in ideologies depicted in the middle of The School of Athens is the painting’s central topic.

Well, who else is there? It’s not always evident, because Raphael doesn’t give all of his characters traits that reveal their identities. Thankfully, there are many on which academics can agree. Socrates is easily identified to the left of Plato due to his striking looks. Raphael is reported to have used an old portrait statue of the thinker as a reference. As Giorgio Vasari points out he may also be recognized by his hand motion.

Even Socrates’ method of thinking is expressed: he places his forefinger between the thumb, and appears to say, “You allow me this.”

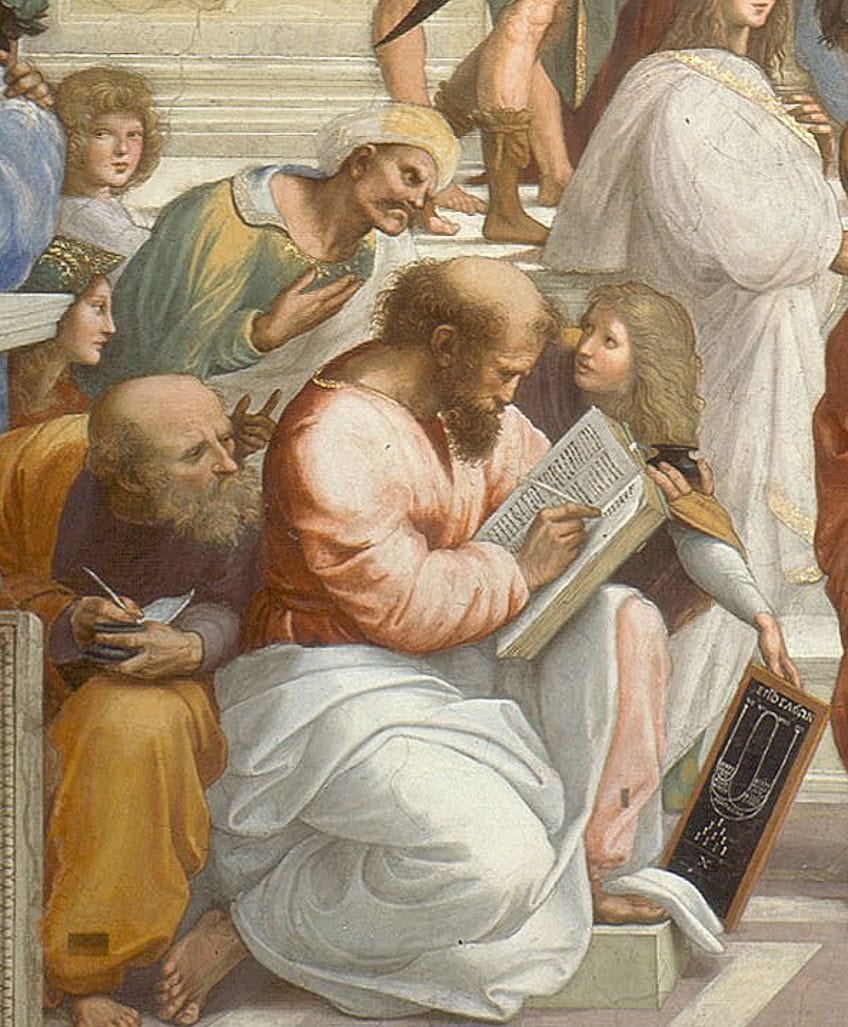

Socrates’ disciples, notably Aeschines of Sphettus and Alcibiades, are among those gathered around him. Pythagoras sits in the front with a textbook and an inkwell, flanked by students. Though Pythagoras is most recognized for his scientific and mathematical accomplishments, he also had a solid belief in metempsychosis.

According to this ideology, every soul is immortal and, following death, transfers to a different physical body. In this context, it’s natural that he’d be positioned on Plato’s side of the mural. Euclid is bending over, displaying something with a compass, echoing Pythagoras’ stance on the other side. His young students are eager to understand the concepts he is giving them.

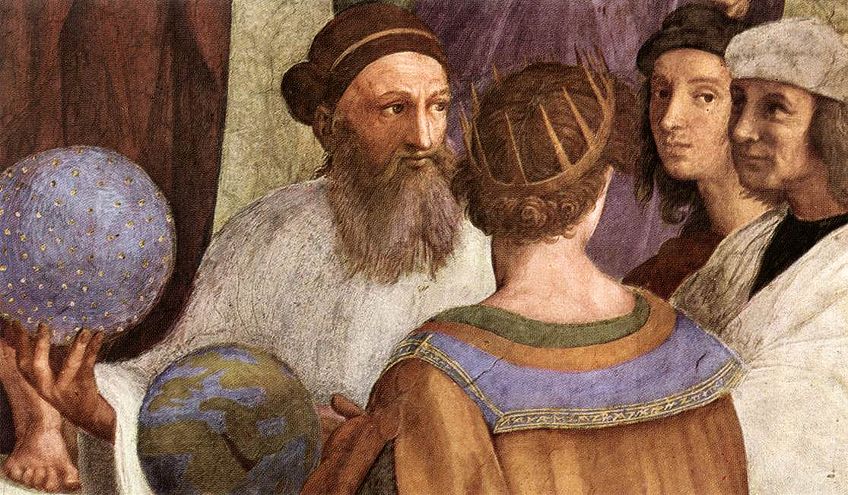

The mathematician is recognized as the “Founder of Geometry,” and his fondness for theorems with accurate solutions indicates why he symbolizes Aristotle’s part of The School of Athens painting. According to experts, Euclid is a picture of Raphael’s pal Bramante. Ptolemy, the famous mathematician, and scientist stands exactly next to Euclid, his back to the observer. He carries a globe of the earth in his hands.

The astronomer Zoroaster is considered to be the bearded person appearing in front of him clutching a heavenly globe. Surprisingly, the young person who stood next to Zoroaster, peering out at the spectator, is Raphael himself. This style of self-portrait was not unknown at the time, but the artist took a risk by integrating his image into a piece of such cerebral sophistication.

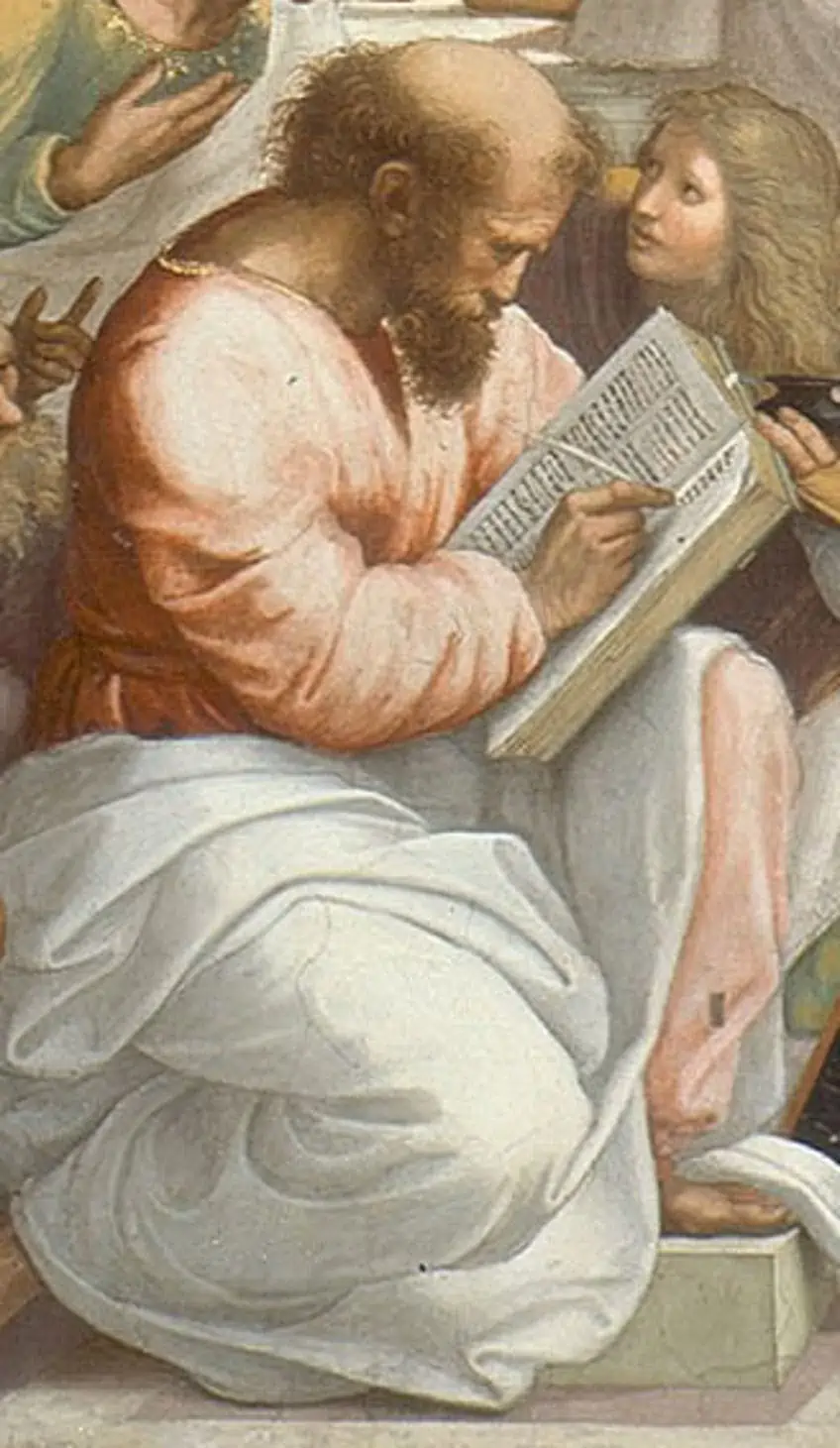

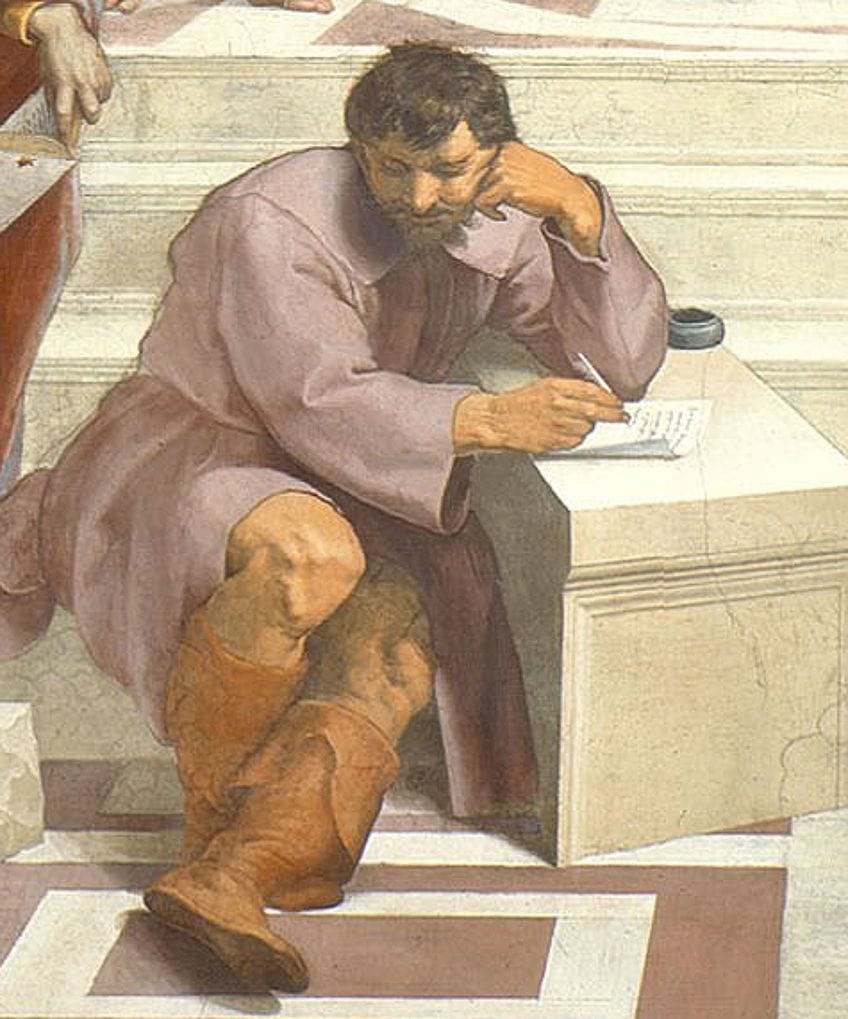

The older person slumped on the steps is commonly recognized as Diogenes. He was a contentious person in his day, having founded the Cynic philosophy and living a modest life. A melancholy figure seated in the front, hand on his head in a traditional “thinker” stance, is one of the composition’s most arresting characters.

Raphael’s earlier sketches do not include this figure, and plaster analysis reveals that it was added later. According to art historians, it is “arguably Raphael’s first effort to borrow some of the heavyweight force of Michelangelo’s Sistine Prophets.”

The somber nature, long assumed to be a depiction of Michelangelo himself, would have complemented the artist’s personality. In the world of intellectuals, he is Heraclitus, a self-taught knowledge trailblazer. He was a sad figure who disliked being with other people, making him one of the few lonely individuals in the mural.

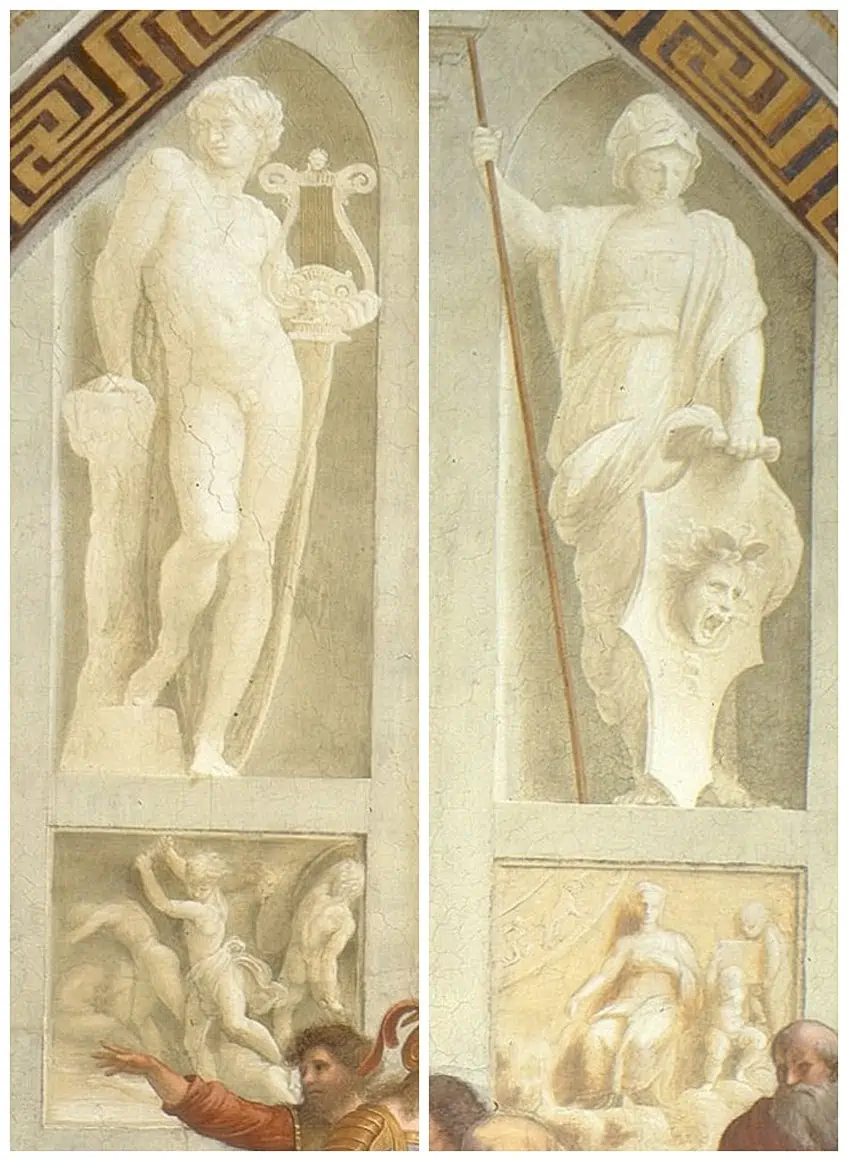

Two enormous figures in recesses at the rear of the school round off Raphael’s program. Apollo is on Plato’s right, and Minerva is on Aristotle’s left. Minerva, the deity of knowledge and justice, is a suitable representation of the fresco’s ethical philosophy side.

Curiously, her posture puts her near Raphael’s jurisprudence painting, which is immediate to her left.

Natural science is represented by Apollo, who is easily identified by his lyre. His role as the god of illumination, music, honesty, and healing places him next to Raphael’s Parnassus painting, which represents poetry and literature.

The School of Athens painting has been a success from its inception, earning Raphael more contracts from the Pope and elevating him to the ranks of Rome’s most sought-after painters. His life was cut short when he died in 1520 at the age of 37, yet his legacy lives on.

He is still regarded as one of the great painters of the Italian Renaissance, and his work continues to influence artists today.

Ambiguous Figures

A dilemma arose as Raphael began to produce preliminary sketches for the big fresco. How could anyone looking at his next picture be supposed to tell one thinker from another? Michelangelo was engaged in crawling on a scaffold under the Sistine Chapel, conjuring up a muscular who’s-who of Biblical heroes immediately identified by their theatrical motions and distinctive props from paints and egg-wash.

Nobody would ever confuse Noah’s rescue of humanity from a huge flood with God’s creation of the planets. But what about Xenophon from Antisthenes? Intellectuals may have diverse views, yet their robes are eerily similar.

Raphael must have realized the tremendous confusion that may follow as he began to assemble his dizzying array of anachronistic characters.

It wouldn’t do to have a befuddled swarm of indeterminate figures sloshing around in a stew of unidentifiable ideas. Sure, it may appear simple enough to distinguish the senior Plato from his pupil Aristotle as the two saunter down the steps in the center of the artwork. After all, Plato is carrying a volume of his Timaeus, a book on the essence of humanity’s existence in the material realm, while Aristotle is carrying a volume of his 10-volume Ethics.

Forcing viewers to stare at the spines of huge tomes jammed cumbersomely into the palms of each character in the picture, on the other hand, would have weighted the piece down with tiresome detail. Raphael seems to have realized, at some point during the creation of his School, that building static and readily distinct identities for his famed students was the incorrect method. Instead, he should embrace the unavoidable uncertainty, openly welcome an unresolvable flux, and so make the unpredictability of identities itself the philosophy of his painting of philosophy.

Observe Plato’s picture again: doesn’t his elderly face and wizened beard coincide uncannily with that of Raphael’s revered elder colleague, Leonardo Da Vinci, as recorded in a well-known self-portrait of the famed painter?

And hasn’t Plato’s hand, gesturing upwards to either paradise or an idealized sphere of ultimate oneness, captured our attention previously in Leonardo’s own image of the follower Thomas in The Last Supper, finished a decade prior? Plato is no longer just playing Plato. Rather, he is a tense amalgamation of shifting egos. Plato becomes a type of melting pot of identities in Raphael’s hands, where the philosopher, the artist, and the embodiment of doubting-all-you-see blend and meld into one.

Observe the person writing in a journal in the left foreground of the mural if you think that intricacy of personality is a one-off in the picture. The tablets at his feet, on which a chromatic scale is etched, unmistakably identify him as Pythagoras. But who is that in his left ear?

Historians have recognized the two figures’ stances and interactions as a double picture of St Matthew, flanked – as he commonly is in period iconography – by an angelic being to his left.

So, the motif of intertwinement continues over the surface of the mural – the interesting interweaving of personalities. The draftsman playing his compass has been convincingly recognized as Euclid and Archimedes. It’s all up to you. What about the uniformed person to the right of Raphael’s composition, who is being chastised by some individual?

Some visitors’ guides to the artwork claim he is Alexander the Great. Others point to Alcibiades, the illustrious Athenian commander. Strabo and Zoroaster’s souls have been merged into a single picture of an astronomer whirling an orb of stars somewhere in the painting, creating a striking merging of identity.

But how can we determine whether any of this is intentional or a component of the artwork’s explicit visual strategic plan? The different spokes of twisted identities that form the static state of being must be tied to a unifying axle – a core among the clamor that may help us make an understanding of the system – in order for Raphael’s painting to operate.

Then our eyes catch sight of it: a modest inkpot with surprisingly rich and profound symbolic meaning.

The item plainly belongs to the contemplative writer whose nib has halted in mid-thought — a character who is completely absent from Raphael’s preliminary studies. He was a later addition, a touch added when the piece was nearly finished. The figure has long been recognized as a combination of more than one historical figure over the ages, just as the other number of available personalities circled him.

On the one hand, he’s said to be a homage to Raphael’s venerated adversary Michelangelo, whose facial characteristics eerily resemble Raphael’s. At the same time, his glum demeanor is reminiscent of that of the pre-Socratic intellectual Heraclitus. Raphael’s last-minute reference to Heraclitus, who is eternally locked in the midst of making his works, is significant to the consistency of his otherwise befuddling fresco. Heraclitus is well known for his meditations on the universe’s continual flux, which are famously encapsulated in the adage “you cannot tread in the same river twice.”

The mists of time would brutally confirm his faith in the transience of all things; hardly a single project of his has endured. Raphael creatively portrays the ebb and flow of existence by rewinding history to a period when the same ink that commemorated the thoughts of Heraclitus, who was known as ‘The Obscure,’ was still fresh, and not yet lost by time.

Heraclitus’ ink pot (from which conceptions of the fleetingness of all power would spill out) is a bravely rebellious symbol that monitors the implementation of formal papal directives in the Stanza Della Segnatura.

It declares the futility of any endeavor to emblazon oneself permanently into the world, therefore denying authority. It and only it legitimizes the fluidity of identification that Raphael deftly develops throughout the canvas. Remove the ink jug from Raphael’s fresco’s center, and the piece devolves into a jumble of jumbled and jumbled shapes. The deep, though ignored, inkpot of Heraclitus is the same well-spring from whence Raphael’s masterpiece’s elastic energy continuously flows.

Setting

The structure is shaped like a Greek cross, which many have speculated was meant to represent a balance between pagan thought and Christian theology. The building’s design was influenced by Bramante’s work, who, according to Vasari, assisted Raphael with the design in the image.

The final design was inspired by the then-new St. Peter’s Basilica. Above the characters, the main arch features a meander (also identified as a Greek key design), a design based on consistent lines that recur in a “sequence of rectangular curves” that arose on Greek Geometric era ceramics and later became popular in ancient Greek architectural friezes.

With that, we conclude our look at The School of Athens by Raphael. The School of Athens painting is recognized as a painting that captures the spirit of the Italian Renaissance. The School of Athens painting was the third of three pieces created for Raphael’s Stanza della Segnatura, a room inside the Apostolic Palace that he adorned.

Take a look at our School of Athens painting webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

Who Painted The School of Athens?

This fresco was produced by Raphael, whose works were the way through which his real love for life manifested itself. His ability to communicate the aesthetic principles of the Renaissance Humanistic age was seen as groundbreaking. Raphael’s works are considered masterworks in the same prestigious category as Michelangelo’s and Da Vinci’s. Raphael’s incredible artistic ability, despite his brief life, was the consequence of years of instruction that began when he was a toddler. Raphael’s canvases were considered as some of the best examples of the age’s humanistic attitude, which tried to assess man’s value in the world via works of pure beauty. Raphael not only mastered High Renaissance creative traits like perspective, precise anatomical accuracy, and real expression of emotion and clarity, but he also possessed a particular style noted for its purity, vivid palette, and clear organization.

What is Plato’s Gesture in The School of Athens, and What is Meant by It?

Plato is gesturing to the heavens with his forefinger. This is a symbol of Plato’s ideology, which places a high value on paradise and transcendental truth. Plato is most known for his theory of ideas, in which he claims that the complete material reality, the delicate world visible through the senses, is a reflection of an intelligible world, the world of ideas, which is not discernible via the senses. As a result, Plato is highlighting the importance of universal truth in the illustration.

Why Were the Greek God Apollo and the Goddess Athena Included in The School of Athens Painting?

The Greek deity Apollo and the deity Athena depict features that connect to the general topic of the Stanza della Segnatura, which was formerly a library with the Pope’s collection, where The School of Athens artwork is located. Apollo is the deity of dancing, music, marksmanship, prediction, and honesty, among other things. Athena, also known as Minerva in Mythological traditions of Rome, is the deity of wisdom and battle, which matched the Pope’s studies of the Humanities, specifically philosophy, literature, justice, and religion.

Jordan Anthony is a Cape Town-based film photographer, curator, and arts writer. She holds a Bachelor of Art in Fine Arts from the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, where she explored themes like healing, identity, dreams, and intuitive creation in her Contemporary art practice. Jordan has collaborated with various local art institutions, including the KZNSA Gallery in Durban, the Turbine Art Fair, and the Wits Art Museum. Her photography focuses on abstract color manipulations, portraiture, candid shots, and urban landscapes. She’s intrigued by philosophy, memory, and esotericism, drawing inspiration from Surrealism, Fluxus, and ancient civilizations, as well as childhood influences and found objects. Jordan is working for artfilemagazine since 2022 and writes blog posts about art history and photography.

Learn more about Jordan Anthony and about us.

Cite this Article

Jordan, Anthony, ““The School of Athens” Raphael – Analyzing This Famous Artwork.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. February 14, 2022. URL: https://artfilemagazine.com/the-school-of-athens-raphael/

Anthony, J. (2022, 14 February). “The School of Athens” Raphael – Analyzing This Famous Artwork. artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. https://artfilemagazine.com/the-school-of-athens-raphael/

Anthony, Jordan. ““The School of Athens” Raphael – Analyzing This Famous Artwork.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source, February 14, 2022. https://artfilemagazine.com/the-school-of-athens-raphael/.