Arte Povera – The Revolution of Making Art With Poor Materials

Arte Povera was arguably one of the most important Avant Garde movements to emerge from southern Europe. The late 1960s art movement’s contribution to art history may often be overlooked, but it resonates in much of what we call contemporary art today, not just in Italy, but in the rest of the world.

Contents

The Memorable Matter of Arte Povera

Arte Povera is radical because of its influence. Arte Povera challenged traditional conceptions of value. It mocked and mimicked the age-old question: “what is art?”, and “who gets to define what art is made of?”. Arte Povera provoked the art world with its complex questions about the future of materiality in the gallery space. On these questions, Arte Povera found its infinite influence on contemporary art.

What Is Arte Povera?

In Italian Arte Povera literally means “Poor Art”. The term describes a style of art that originated in Italy in the late 1960s. The Arte Povera movement could arguably be linked to several American art movements of the time. Art history is filled with beautiful objects of gold, silver, bronze, jewels, marble, and other durable materials. Even painters have traditionally chosen exquisite paints and the finest canvas. Arte Povera artists used distinctly non-traditional and temporal art mediums to create their work.

Their poor everyday materials challenged the utopian ideals of the pristine gallery space.

In borrowing forms and materials from ordinary life, these artists used materials commonly found around the home to create their work. Arte Povera demonstrated a love for everyday objects and the body. Though made from banal materials, the work often required movement and a spatial relationship with the object that went beyond interpretation. Arte Povera’s particular use of materials from the pre-industrial era, such as earth, stone, clothes, paper, rope grass, wood, and other natural elements highlighted a deep interest in physicality and materiality. Engaging with notions of nature, environments, and urbanization provided these artists with a diverse range of aesthetic possibilities.

The Indelible Influence of Marcel Duchamp and the Readymade

After World War I, many artists were disenfranchised, and the world suffered a deep malaise with a society that had been exposed as capable of such atrocities. Artists sought new ways to innovate and break out of traditional or historical modes of art making. The pioneer of Dadaist Marcel Duchamp had been a successful painter known in Paris for his own brand of Cubism. At some point, he stopped painting almost entirely, in his quest for alternative modes of representing objects. Eventually, Duchamp began selecting commercially available, mass-produced, often utilitarian objects, signing them, and presenting them as artworks.

Duchamp’s “Ready-mades,” as he called them – these ordinary objects the artist selected, modified, and challenged centuries of ideas around the artist’s role. As a skilled maker of original and beautiful handmade objects. Duchamp’s readymade works include Bicycle Wheel (1913), Bottle Rack (1914), and Fountain (1917) Marcel Duchamp’s famous use of a urinal as a work of art. By simply selecting, repositioning, titling, combining, or signing them, everyday objects become art. The readymade injected a spontaneous, fresh element into society’s attitude towards art, its purpose, or potential. Duchamp introduced the idea of bringing an everyday object into the gallery, bringing something of the real world into the gallery space. The readymade defied the notion that art had to be beautiful and paved the way for Conceptual Art, which concentrated on presenting ideas rather than the visual attributes of an artwork. By being the first to bring the everyday object into the gallery space Marcel Duchamp became influential in the development of Arte Povera.

The Origins of Arte Povera

In the post-war period, Europe saw itself changing rapidly due to an economic boom that produced a positive incline for industries, capitalism, and general living standards. The global sentiment was that peace had come, the war was over, and people now had independence, and emancipation, and could experiment and have new ambitions. Of course, that sentiment reached Italy where there was general development and it seemed things were getting better. From the 1950s to the 60s, Italians were suddenly able to afford all the wonderful things that had been inaccessible before and during the war. Miraculously, at the start of the 1960s Italy’s then currency, the Lira briefly became the most stable currency in Europe. Italians call this moment Miracolo Italiano meaning the Italian miracle and depicting the great sense of hope for Italy at that time.

However, this great access led to excess and eventually expenditure. Suddenly, Italian artists who had 2000 years of art history to live up to, looked around them and found that everything had been either industrialized or Americanized.

Miracolo Italiano had simply swapped their cultural identity for the American version. Everywhere these artists turned they saw American companies, American products, American movies, American stars, and American art. This feeling of conflict and alienation was the foundation of Arte Povera. Even outside of art, this was an intensely political period for Italy which had just grappled with its own distinct brand of Fascism. As the world surged into a new era of change, the Italian economy was in decline. Political angst and the rebellion of a new generation were in the air and the 1968 revolution would come a year after Arte Povera, which was born in 1967. The art critic Germano Celant (b. 1940) first contextualized this movement when he brought a group of artists together in a 1967 exhibition he called Arte Povera. Celant didn’t just coin the term Arte Povera, he also wrote the Arte Povera manifesto, which he published in a 1967 edition of Flash Art. In the piece, Celant declares the minimalist, uncompromising aesthetic, and conceptual implications of Arte Povera.

The Arte Povera Movement

The Arte Povera movement unfolded mostly in northern Italy in cities like Roma, Milano, Genova, Bologna, and Torino. In a time when getting a hold of more expensive art supplies was not always easy for Italian artists. Their rejection of expensive and durable materials could be seen as having been borne from both necessity and resourcefulness. Arte Povera artists had to get economical. They had no choice but to use odds and ends from around the house and natural materials to create art. Arte Povera artists rebelled against the art which preceded the war. They chose the medium of sculpture to break away from the Modernist abstract painting that dominated European art in the 1960s. Arte Povera artists criticized Abstract painting for being constrained by painting traditions and focusing too exclusively on individual expression.

Because Arte Povera artists had similar techniques and ideas to movements like Pop Art, it is important to point out that Arte Povera specifically rejected the Pop Art aesthetics of American art at the time. Unlike Andy Warhol or Roy Lichtenstein’s flirtations with consumerist culture, Arte Povera was sternly against it. However, Arte Povera’s somber use of untreated materials that reflect the reality of consumerist culture yielded some of the movement’s most iconic artworks. As a result, the movement has then been compared to Minimalism, artists also rejected American Minimalism’s obsession with technology and its monopoly on the art world. There are more similarities between Arte Povera and the post-Minimalist movements of American art in the 1960s.

Arte Povera had also been compared to Conceptual Art, Fluxus, and New Realism because of its subversions of generally accessible materials.

Like these various other movements, Arte Povera sought to find different forms of expression and it happened to be found in objects. However, Arte Povera always maintained its distinction. It is only partly like these movements. Its cultural context includes them but is not bound to them. Indeed, Arte Povera had a deep mistrust of modernity and Americanization. Its own aims were to preserve and recreate its own communal memory and tradition. It evoked the past in a distinctly contemporary, local, and Italian way.

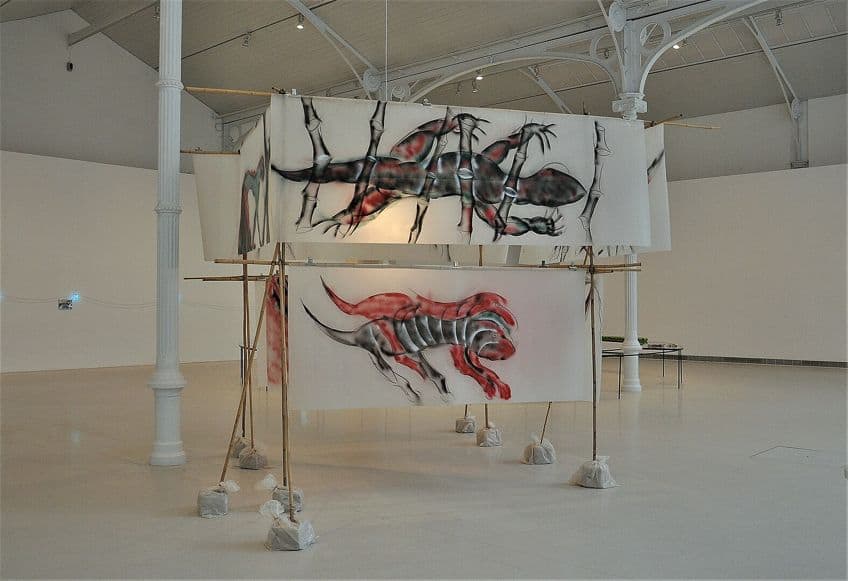

Six Arte Povera Artists

While Arte Povera is often compared to American movements that were happening at the time, its artists rejected this juxtaposition. For example, they did not relate to Minimalism’s technological and scientific rationale. They inhabited a more mythic, poetic realm to contrast American Modernism’s systematic approaches. Arte Povera centered the individual in a time when the consumerist culture encouraged homogeneity. Arte Povera artists were interested in performance art which aligned with their ideas of the ephemerality of art. Because of its preoccupation with the body, performance art can manifest itself in quite existentialist forms, conjuring questions of identity and meaning. Therefore, Arte Povera can ultimately have spiritual connotations. While heavy and durable materials are the ones typically found in museums, Arte Povera explored permanence and temporality through works and ideas that were always in flux.

Arte Povera was also quite futuristic for its rejection of binaries and categories. By using non-durable and everyday materials and materials, these artists tended to challenge certainties viewers might have had about art. Even in comparison to their American counterparts, Arte Povera artists entered a space of fluidity long before fluidity was the cultural norm. Artists such as Lucia Fontana, Giovani Anselmo, Marisa Merz, Jannis Kounellis, Giuseppe Penone, Pino Pascali, and Michelangelo Pistoletto challenged conventional cultural values with their irreverent approaches to materiality. Their structures made of natural textures and ordinary man-made objects expressed their existential longing and embodied their political realities.

Mario Merz (1925 – 2003)

| Date of Birth | 1 January 1925 |

| Date of Death | 9 November 2003 |

| Place of Birth | Milan, Italy |

| Nationality | Italian |

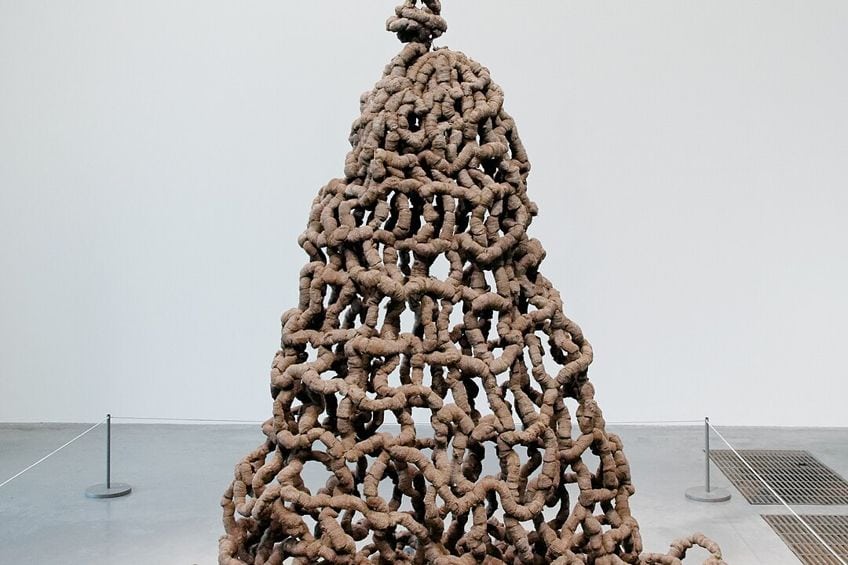

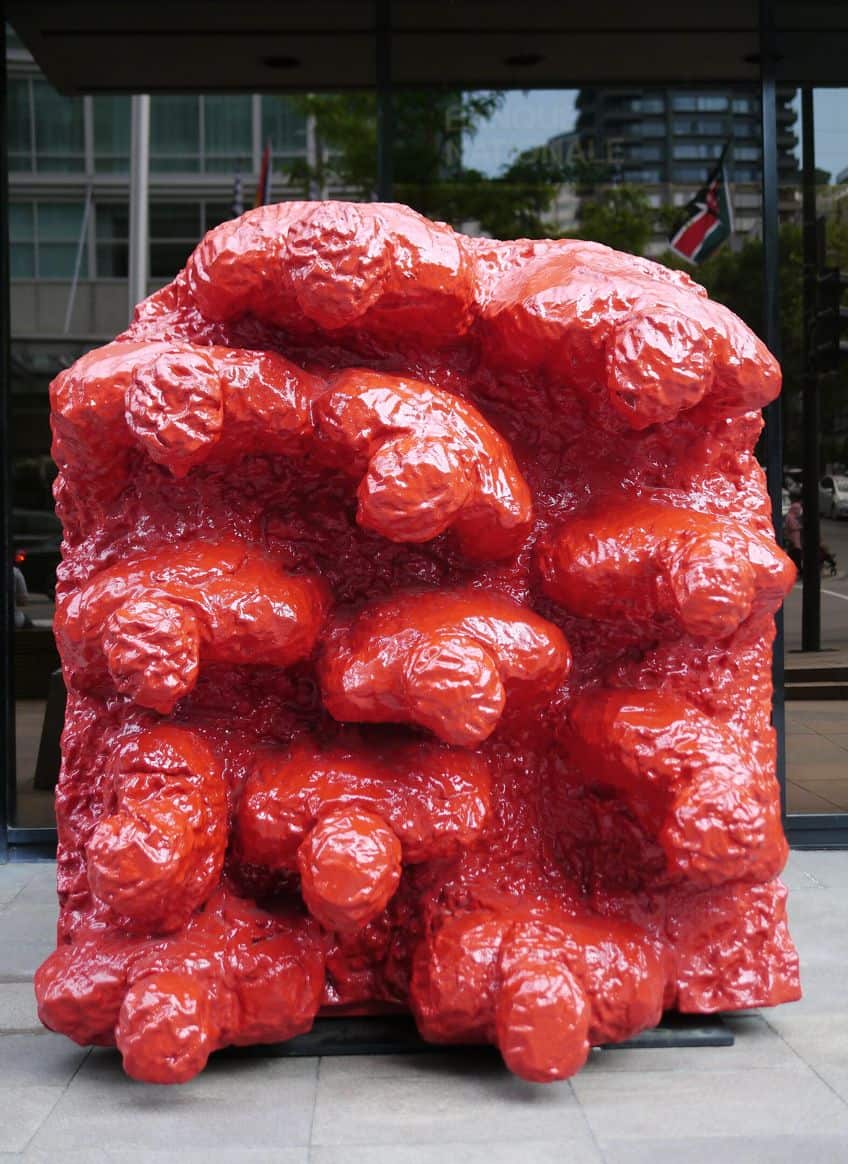

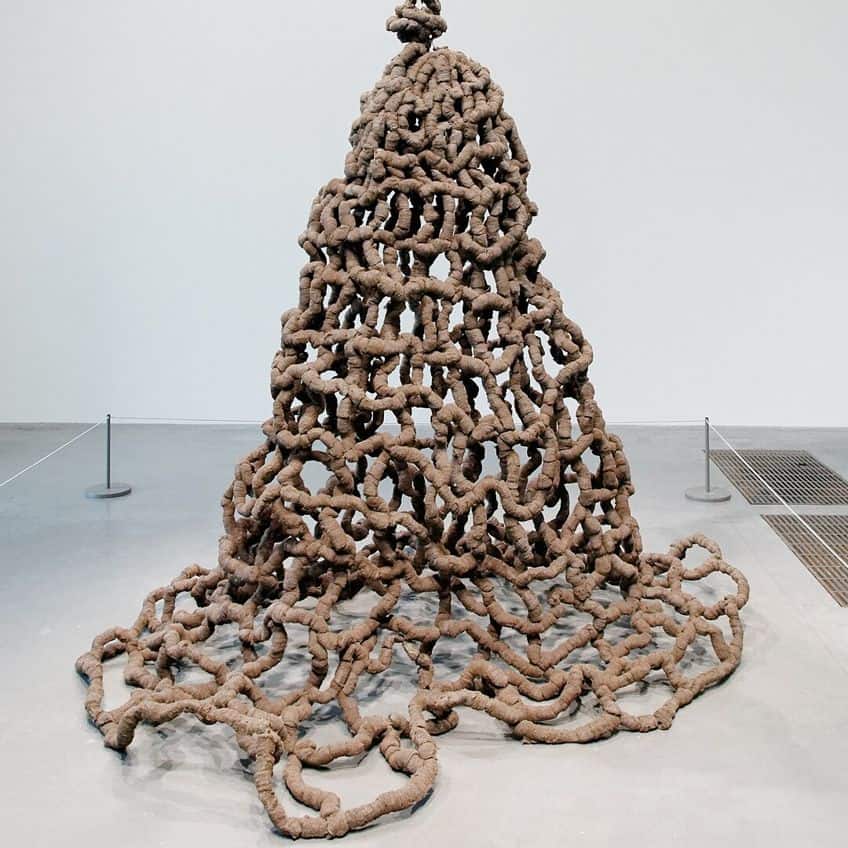

Mario Merz is considered an important artist of the Arte Povera movement because he elevated poor materials to the point where they exceeded the viewer’s expectations of what poor materials could amount to. The monolithic structure Il Cono (1967) resembles a cone that seems to belong in both the past and the present.

Made of woven wool, it has a haystack quality and conjures agricultural notions, making the viewer envision it somewhere in the countryside. Il Cono is an imposing structure that requires a level of negotiation.

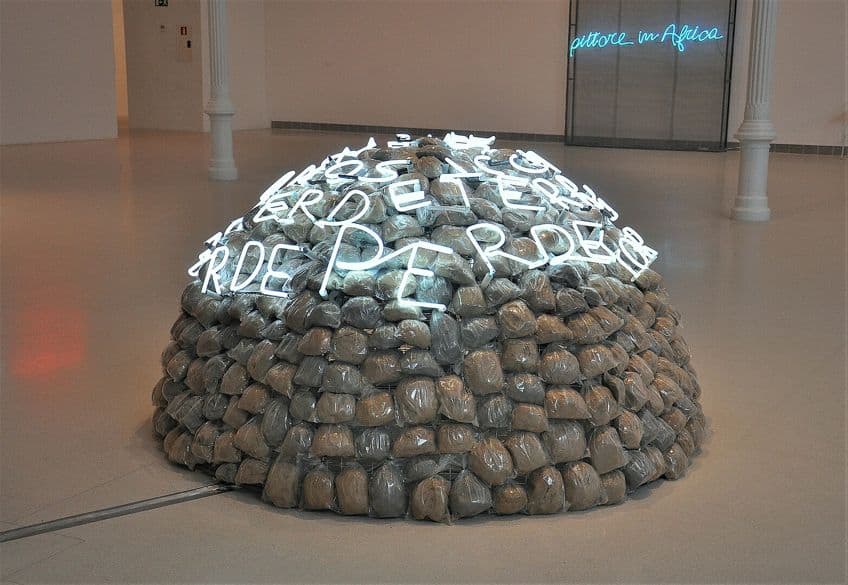

Mario Merz’s Giap’s Igloo () is an igloo made of soil and wire and covered in neon letters. It’s the first in a series of igloos by this artist which all combine in some way neon text and rugged construction materials. Merz’s igloos represent his interest in the essentials of life such as shelter, food, and warmth. The igloo alludes to simpler notions of survival, but the works also included technical tubes hinting at more specifically modern realities, like consumerism and advertising.

Marisa Merz (1926 – 2019)

| Date of Birth | 23 May 1926 |

| Date of Death | 20 July 2019 |

| Place of Birth | Turin, Italy |

| Nationality | Italian |

Marisa Merz is a key Arte Povera artist. Her most well-known work Untitled (living sculpture) (1966) consisted of air conditioning viaducts. Merz used this everyday material to create an abstract composition that hangs on the ceiling. Many Arte Povera artists would use everyday objects to create architectural forms, like a door obstructed by bricks or towers made of doilies, usually vertical structures, that appear to mimic buildings.

Marisa Merz departed from this and introduced free-flowing aesthetics that hinted at the biological.

In Untitled (living sculpture) (1966) the metal strips are woven into circular forms to suggest life. They could be tentacles or plants spreading across a canopy. It is not just the aesthetic, but the methodology behind this work that mimics the state of being alive. Whenever the work is uninstalled, the succeeding curators are at liberty to exhibit it however they prefer. Other than the fact that it should hang from the ceiling, there are no prescriptive instructions for exhibiting the work. One is reminded of this idea of life when experiencing the piece in the gallery space. The light weight of the material allows it to sometimes move either with people walking past. or even the air conditioning. Untitled (living sculpture) continually morphs and remakes itself.

Piero Manzoni (1933 – 1963)

| Date of Birth | 13 July 1933 |

| Date of Death | 6 February 1963 |

| Place of Birth | Soncino, Kingdom of Italy |

| Nationality | Italian |

Piero Manzoni‘s work Linea (1959) is nothing more than a cylinder. The title Linea in Italian translates to ‘line’. The cylinder is sealed, but it is labeled, claiming that the cylinder contains a line of a particular length. The work played with the viewer’s imagination, allowing them to picture the characteristics of said line.

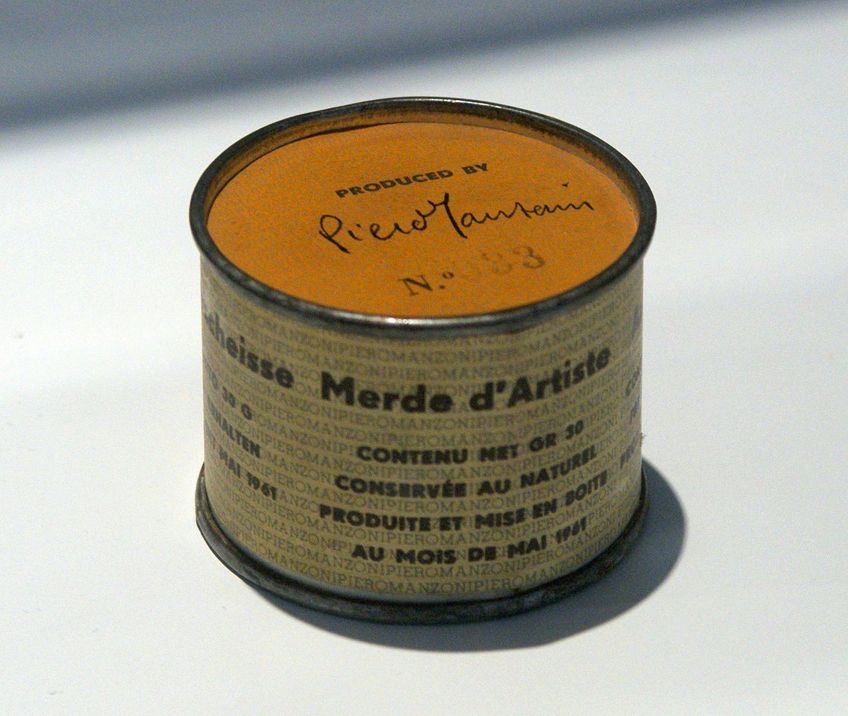

But by far Piero Manzoni’s best-known piece is Merda d’Artiste (1961), otherwise known as Artist’s Shit.

Artist’s Shit is a shining emblem of the Arte Povera movement. The piece allegedly contained 30 grams of the artist’s own feces. The limited series with 90 pieces were created, canned, and labeled identically at his father’s cannery, satirizing mass production, consumer culture, and the fetishization of the art object. Even though exhibition visitors could never tell whether the cans genuinely contained feces the Artist’s Shit cans were sold at the market price of gold by weight. In 1961 the value of gold per ounce was $35.09 meaning Artist’s Shit would have cost roughly $37. Opening the cans would jeopardize the integrity of the artwork. All of these aspects worked in their own way to challenge notions of value in art.

Michelangelo Pistoletto (1933 – Present)

| Date of Birth | 23 June 1933 |

| Date of Death | Present |

| Place of Birth | Biella, Italy |

| Nationality | Italian |

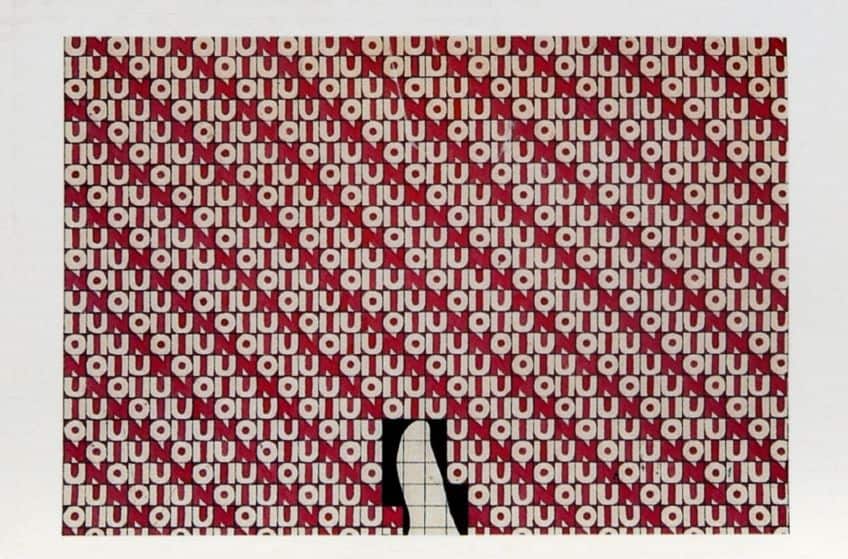

Michelangelo Pistoletto is known to work with mirrors. Moltiplicazionne e Divizione dello Specchio (1976) is a mirror placed in a corner of a room, reflecting itself infinitely, creating a feedback loop and an illusion of three-dimensionality. In the mixed media work Opificio Pastiglia Leono (2018), Michelangelo Pistoletto’s used stainless steel. Though the steel has been polished to a mirror onto which Pistoletto either painted or transposed photographic imagery.

These works confront ideas of painting as finite as the objects perpetually absorb their environment, internalizing it. When a viewer stands in front of the artwork to view it, they transform it.

Michelangelo Pistoletto’s Structure for Talking While Standing () has a similar effect. As the title suggests, this work offered a structure to rest upon while guests converse, having been inspired by an exhibition discouraging people from leaning against the art. This sculpture is perpetually unfinished in the sense that it requires audience participation. Pistoletto was very interested in the idea of art that can only be completed through activation and human interaction.

Alighiero Boetti (1940 – 1994)

| Date of Birth | 16 December 1940 |

| Date of Death | 24 April 1994 |

| Place of Birth | Turin, Italy |

| Nationality | Italian |

Alighiero Boetti is one of Arte Povera’s most integral artists. The body is an important element in the Arte Povera movement, and the sizes of Boetti’s work refer to the human body. Boetti’s work invites viewers to meander around and explore the piece. Arte Povera cherished work that led the viewer to change their perspective, both physically and conceptually.

Catasta (1966 – 1967) comes in the form of layered ethernet tubes which allude to architectural modules.

They are a modern formation of elements that support one another creating a tower that plays with notions of inside, outside, natural, and artificial. In 1968 Boetti constructed Collonne (1968) by stacking doilies up like towers or columns from classical temples which brings up notions of space and time and the idea of durability. Arte Povera was known for promoting the idea that ultimately a work of art was not something destined to last forever. Through the simple construction of putting a hole in the middle and connecting them with a strong pole, this very poor throwaway material has been turned into an emblem of sturdiness and durability. The scale of this thin, irreverent material, is transformed once it adds up until the columns, resemble skyscrapers. and become sturdy vertical, imposing structures.

Eliseo Mattiacci (1940 – 2019)

| Date of Birth | 13 November 1940 |

| Date of Death | 25 August 2019 |

| Place of Birth | Cagli, Italy |

| Nationality | Italian |

Eliseo Mattiacci’s provocative work Tubo (1967) is a 150-meter-long tube that snakes around the gallery space until it bursts right out of the gallery doors. Part of the exhibition is in the gallery space, and part of it spills out onto the stairs and all around the building. In the gallery space, Tubo curls around itself, so that it reads something like a Minimalist artwork. But as the viewer approaches, and navigates the artwork, other associations may arise. It could conjure calligraphic notions with its almost written curvature. It begins to resemble a drawn form. Then it meanders toward the abstract.

Remaining always loose and open to a myriad of interpretations.

When it exits the door, negating the institutional perimeter looks more and more like utilitarian work. As they walked up the stairs, approaching the gallery doors, a visitor to the gallery might be forgiven for simply thinking that the workers had forgotten this yellow, snaking tube, spiraling out of place amongst other works of art. Tubo doesn’t announce itself as a work of art. It subliminally asks the viewer to recognize it as such. Playful as it may appear, this work makes a respectable attempt at exploring the age-old conundrums of the art canon. By letting the work escape out the door Mattiacci challenges historical conventions of what art is, where, and how it may be displayed. It makes the viewer cognizant of the traditions and expectations around the act of viewing and interpreting art.

Three Things You Didn’t Know Could Be Art

Part of the manifesto if you like of arte povera was to challenge the way we conceive art fundamentally. As such, one of the biggest ways in which artists did this was by using unusual objects and calling them works of art. We can see this clearly in the works of Duchamp, but some artists took this even further. Duchamp manipulated his found objects, turning them around or placing unusual objects together, and in this way, he was actively creating art.

Some artists, however, simply let the objects themselves stand as works of art.

A Floor

Floor Tautology (1967) by Luciano Fabro comprised a cleaned and polished floor section that had been demarcated and covered with newspapers to dry and prevent scratches or scuffs. By focusing on an often-overlooked section of a particular space, this installation challenged viewers’ perceptions of value, encouraging them to consider the beautiful banality of maintaining a clean floor. The audience contributes to the artwork by maintaining the cleanliness of the space and not disturbing the newspaper.

Some Water

Pino Pascali’s Thirty-Two Square Meters Of Sea (1967) consists of containers filled with colored water mimicking the natural colors of the ocean. The variance of colors gives the impression of light, and movement often seen on vast areas of water. The tension between the natural and the artificial in Pascali’s Thirty-Two Square Meters of Sea is achieved through his subtle color work. The natural color of each water container is naturalistically familiar.

Yet the abrupt change between the colors in each cube reminds the viewer of their artificiality.

The artificiality of Pascali’s containers speaks to notions of replication, and the limits of technology. Thirty-Two Square Meters Of Sea serves as a reminder of humanity’s overbearing influence on nature. In addition, Pascali also nudges the viewer back toward the long and lush history of artists attempting to depict and encompass the impossibly vast ocean.

Stones in a Door

The title of Janis Kennellis work Senza Titolo (1959) means stones in a door. Kennellis conjures notions of accessibility and denial. By blocking a door as he does in Senza Titolo, the artist embodies a confrontational position. A position of refusal. As he sources the stones, scouring the surrounding area of the museum to source local materials, the artist engages ideas of place, belonging, and performativity.

He invites the viewer to consider the skill required to accomplish such a perplexing feat.

While Kennellis has obscured the artist’s hand in this work, the amount of effort it would take to mount this piece is undeniable. Perhaps Kennellis wanted us to juxtapose the skill of the bricklayer with that of the artist. To consider the synergies between a bricklayer’s effort, and an artist’s statement.

Arte Povera in Summary

Unlike classical paintings which have become so naturalistic and familiar to us, Arte Povera presents its own version of reality. Arte Povera sees forms such as representation as deceptive. They may depict natural objects, trees, skies, humans, and everyday objects, but they are illusions. The material reality of that object is paint. Instead, Arte Povera, transforms poor materials into artworks to explore notions of perception and space. The simple magic of Arte Povera is that it alludes to a dimension obscured by banality.

By 1972, Arte Povera had made an undeniable impact on the global art world. Though it may not always get the credit it deserves, the style of Arte Povera is now more common than ever. To this day contemporary artists like Mike Kelly, Tracey Emin, Martin Creed, or El Anatsui could be considered proponents of this style. This art form removes the requirement of skill from the artist’s hand until what’s left is a notion, creating a different kind of dialogue between the artwork and its viewer.

Arte Povera artists demonstrated well-known avant-garde provocations. At the time, these were new and challenging aesthetics that diverted from the norm, making people reconsider their presuppositions about art. In their complex cultural context, they critiqued consumerism and capitalism, and already had deep-seated environmental concerns. They took use of everyday objects and elevated them to art objects in their attempts to critique humanity’s relationship to the environment, and our culture of consumerism.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is Arte Povera Linked to Assemblage?

The worldwide artistic movement known as Assemblage uses similar materials and is often connected with Arte Povera. Assemblage also emerged as a response to Abstraction, which had been the dominant movement at the time.

Did Arte Povera Come Out of Fascism?

Most Arte Povera artists credit Alberto Burri’s influence, as he was the first Italian artist to be known for his use of poor materials. However, Burri was a known fascist.

Does Piero Manzoni’s Artist’s Shit Have Actual Excrement in It?

The artist Bernard Bezilei made his own artwork, Ouverte de Piero Manzoni (1989), by purchasing a Manzoni can and opening it only to find nothing but cotton wool and plaster. While this is somewhat disappointing, there is no way to know whether there are some real ones out there.

How Much Is a Can of Artist’s Shit?

In 2007, an unopened can of Piero Mazoni’s Artist’s Shit sold for $139,000.00, and again in an art auction in Milan in August 2016 for $308,000.00.

What Happened to Piero Manzoni‘s Fiato d’Artista?

Fiato d’Artista (1961) can be translated from Italian as artist’s breath. It is simply a red balloon that Manzoni inflated and affixed to a plinth. Unfortunately, this entire series of work that was said to contain the famous Arte Povera artist Piero Manzoni‘s breath became deflated over time.

Liam Davis is an experienced art historian with demonstrated experience in the industry. After graduating from the Academy of Art History with a bachelor’s degree, Liam worked for many years as a copywriter for various art magazines and online art galleries. He also worked as an art curator for an art gallery in Illinois before working now as editor-in-chief for artfilemagazine.com. Liam’s passion is, aside from sculptures from the Roman and Greek periods, cave paintings, and neolithic art.

Learn more about Liam Davis and about us.

Cite this Article

Liam, Davis, “Arte Povera – The Revolution of Making Art With Poor Materials.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. September 27, 2023. URL: https://artfilemagazine.com/arte-povera/

Davis, L. (2023, 27 September). Arte Povera – The Revolution of Making Art With Poor Materials. artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. https://artfilemagazine.com/arte-povera/

Davis, Liam. “Arte Povera – The Revolution of Making Art With Poor Materials.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source, September 27, 2023. https://artfilemagazine.com/arte-povera/.