Installation Art – An Investigation of Art Installation Pieces

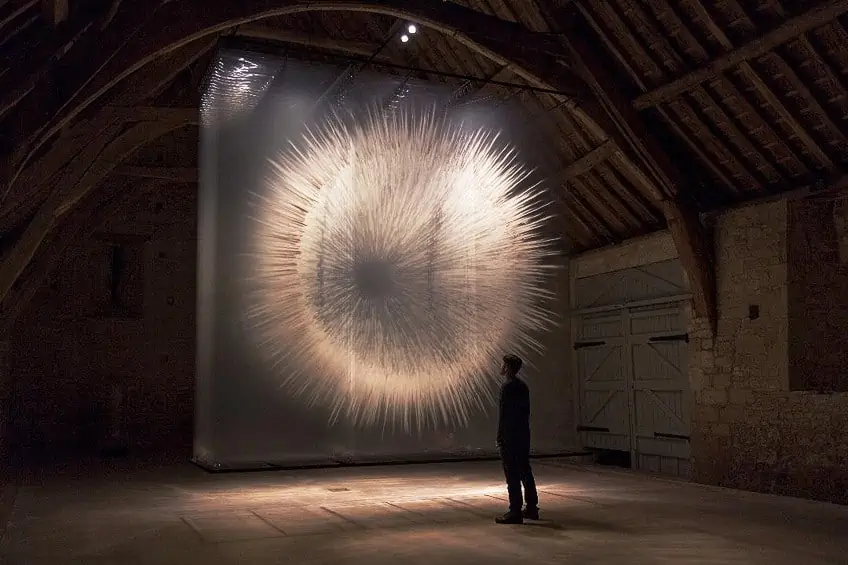

What is Installation art? Installation artists create works within an interior three-dimensional space, and the art installation is usually designed to have a particular social, conceptual, or architectural relationship with the space it is housed in. Unlike traditional art forms, Installation sculptures require a degree of interaction, as the object is not something one looks at, but rather something one walks through and experiences. Today, we will look at the history of installation in art, as well as analyze a few notable Installation art examples.

What Is Installation Art?

Installation artworks are created to elicit a certain feeling or atmosphere, requiring the audience to interact with the piece. Although art installation is in many ways similar to and overlaps with other forms such as Public art, Intervention art, and Land art, it is distinct enough to be classified as its unique form. Installation artworks are often more conceptually significant than they are technically or aesthetically worthy of merit.

Installation artists advocated this art form for its ability to potentially change the way art was perceived by producing works that engaged and surprised those who viewed them in unique and captivating ways.

The History of Installation in Art

Art installations represented a shift in the focus of an art piece from how it looked to what it communicated. Installation artists sought to alter the viewer’s subjective experience. In many ways, Installation sculptures are reflections of our own lives and beings – always in communication with the surrounding world.

Early Influences

There was no single collective drive that led to the emergence of Installation artworks, instead, it was the organic influence of several movements that were experimenting with various conceptual and site-specific artworks. Many regard the conceptual works of artists such as Marcel Duchamp to be the initial inspiration for recontextualizing objects by placing them in unexpected arrangements and settings.

The avant-garde Dadaism movement’s focus on the message instead of aesthetics was another source of inspiration for Installation artists.

Artists such as Kurt Schwitter and El Lissitzky are also often cited as initial influences, with their conceptual concerns over materials and space, as well as the concept of Spatialism – an art movement that sought to produce a new form of art through a synthesis of time, motion, space, imagery, and sound. Along with theater performances, particularly those by the Japanese Gutai, these influences over time began to combine, resulting in the emergence of Installation in art.

The concept of installation in art was not entirely new though, and in the 1950s and 1960s, artists such as Allan Kaprow turned galleries into expressionistic “environments” that guests would walk through.

Other conceptual artists such as Yves Klein also paved the way with works such as The Void (1958) – an empty white gallery space that required the viewer to consider the actual environment as the art piece – a concept that would lay the foundations of art installations

Installation Artwork in the 1970s

The label “installation art” was first used in the 1970s to characterize works that were concerned with the totality of the spaces they filled as well as the viewer’s experience. The art world underwent a period of experimentation that eroded the borders between genres throughout this decade of political, social, and cultural change.

Installation artists were becoming especially interested in creating works that could be exhibited in surprising ways and that considered the viewer’s overall subjective perception.

For instance, during the 1970s, Bruce Nauman’s cramped and confined works played with the viewer’s feelings of uneasiness and intended to make them feel out of sync with their environment. The series of passageways and rooms would lead to an increasing sensation of claustrophobia and abandonment.

A Shift in Artistic Focus

To characterize Installation artwork, art critics first concentrated mainly on its site-specific and temporary nature, but this emphasis altered when advocates of the genre started to develop work reflecting cultural situations and societal issues. During the late 1970s, debates over art’s connection to people’s everyday socioeconomic realities drove the development of Installation art.

The rise of contemporary art galleries and the popularity of large-scale exhibits in the 1980s set the ground for Installation artwork’s subsequent popularity.

Through (1983 – 1989) by Cildo Meireles, for instance, was a highly politicized work that urged visitors to navigate a maze of hurdles, smashed glass, and other bewildering obstacles. The work was intended as a critique of materialism, social oppression, and political restriction. By the 1990s, more direct audience interaction has emerged as a crucial topic for Installation artists. Home for Pigs and People (1997), for instance, was designed by Rosemarie Trockel and Carsten Holler as a metaphor for societal division and consists of a house divided in half by a sheet of one-way mirrored glass.

People lived on one side of the home, while pigs lived on the other, and the mirror allowed the human residents to see the pigs but not the reverse. The artists believed that by completely immersing audiences in the subject they were attempting to portray, they would have a sensory rather than a cerebral experience.

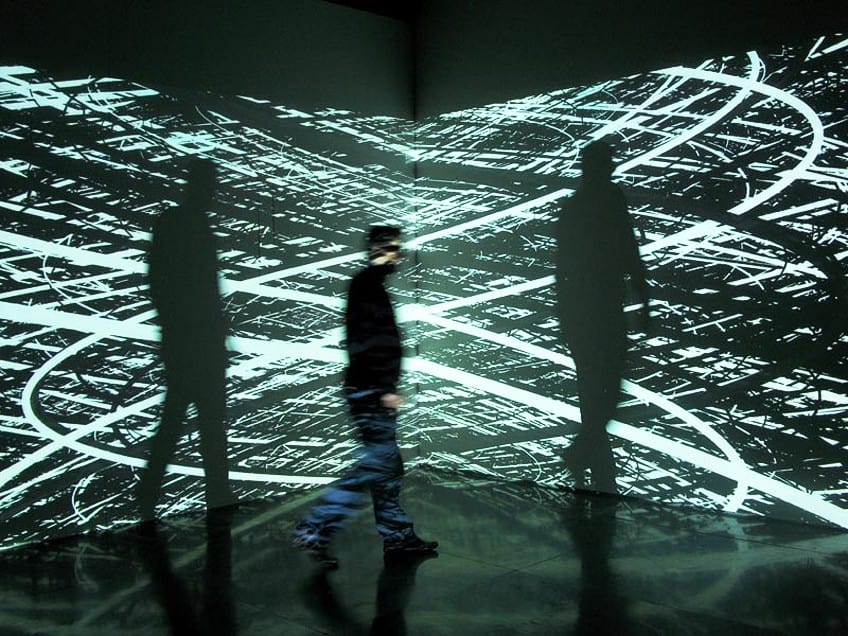

Installation artwork has witnessed an upsurge in the integration of ever-evolving technological developments into pieces that provide increasingly more immersive settings since the 2000s.

Sensors, light, computers, and video projections are used in these extremely engaging pieces, which might be gallery-based, web-based, or even mobile-based projects. Some artists create these installation works so that they react to audience participation, such as Brain Factory (2016) by Maurice Benayoun. The project turns visitors’ thoughts into visual data using a 3D printer, allowing the spectator and machine to collaborate to create the artwork. The viewer’s brainwaves are used as abstract material to guide the realization of physical objects and installation sculptures.

Art Installation Styles and Concepts

Disillusioned with the art world’s rising commercialization, artists started to deviate from creative standards in pursuit of alternatives throughout the 1960s. Numerous installation artists started to make work that was purely intended to function in interaction with a specific site. As a result, removing it from the location would render it pointless.

Site Specificity

Walter de Maria’s New York Earth Room (1977), which is currently on exhibit at the Dia Art Foundation, is a perfect illustration of this. The installation comprises a whole room packed with dirt – de Maria’s attempt to incorporate nature within, to contain what is commonly seen as uncontainable. Andy Goldsworthy has undertaken comparable attempts at nature manipulation. He is known for using mud to cover full walls in exhibitions and other architectural areas.

The pieces literally alter and decay as the mud hardens and splits, allowing visitors to experience deterioration in real-time.

Eberhard Bosslet, a German artist, draws inspiration for his creative ideas from existing environments. Since 1985, he has made several interior pieces utilizing industrial construction materials that function as structural bodies that blend well into existing architectural structures. Kara Walker is recognized for attaching her black silhouettes reflecting the African American experiences straight onto walls, ensuring that her messages about racism’s ubiquity cannot be erased or removed.

The Effect of Conceptualism

Installation art intersects with Conceptual art as both emphasize the significance of ideas above technical prowess. Conceptual art, on the other hand, is generally confrontational and object-based, whereas Installation artworks are often subdued and minimalist. Jenny Holzer’s work, in which she conveyed her own beliefs about the human condition through text-based lighting projections and LED sculptural signs over the walls of numerous public buildings, is one instance that connects the two movements.

Her ideas merge with the environment and invite visitors directly inside her innermost thoughts.

Visitors to Ai Weiwei’s Sunflower Seeds, 2010 at the Tate in 2010 were permitted to take one of (almost) a billion small porcelain seeds placed on the floor of the entire exhibition space, as well as comments on the geopolitics of economic and cultural interaction surrounding the phrase “Made in China.”

Focus on Engagement

Installation art pieces in this class change the emphasis from art as a mere item to art as a catalyst for conversation. By purposefully filling spaces, the artwork drives visitors into tangible closeness, making watching Installation art more comparable to an act of involvement than reflection. “I always strive to create work that stimulates the audience to be a co-producer of our shared world,” artist Olafur Eliasson has remarked.

Cai Guo-Qiang, a Chinese artist, personifies this idea. He produces public bursts of works that rival thrilling firework shows after strategically putting gunpowder on large surfaces or buildings.

After the sparks have died down, there remains beautiful, soot-dark artwork to admire. Rachel Whiteread is another artist recognized for large-scale installations that encourage viewers to contemplate interior space. She filled an entire space at the Tate Museum with numerous white cubes cast from the insides of discarded crates and containers.

Guests were driven to ponder on all the “ghosts” of interior places in their own lives as they strolled through and among these impressions of negative space. Some installation artists design totally immersive installations to absorb the audience in a world apart from reality. These artworks serve as immersive activities for engaged visitors.

Yayoi Kusama’s Infinity Room (2016), an art installation within a complete room of the Broad Museum that ticket-holders enter one at a time to explore alone, is a perfect example. The black area illuminated by hundreds of tiny lights evokes feelings of being in outer space.

Artists in this genre are progressively attempting to engage the audience’s every sense through scent, music, performance, and immersive virtual reality as technology develops. Nathaniel Stern’s works frequently require close engagement with visitors, since the movement of visitors’ bodies triggered various processes by the artwork.

Making Use of Large Spaces

Grand initiatives that turn public settings into contemplative spaces have long been associated with Installation art, with large-scale commissions being essential components of most major art institutions. These Installation sculptures make big statements and are popular with the public, but others claim that they have become extremely pervasive and kitschy, with public appeal considerably outweighing artistic quality.

Furthermore, well-known artists frequently appear to turn to the creation of these gigantic Installations that are likely to capture the public’s interest and propel their reputation.

Christo and Jean-Claude, well renowned for their stunning outdoor installations, once filled the atrium of Philadelphia’s Institute of Contemporary Art with a two-story-high mastaba made of around 1,240 oil barrels that people could barely walk around in navigating the area. Some of Anish Kapoor’s most well-known works fall under this category, particularly his massive sculptural structures that sometimes take over many spaces, rooms, and even stories.

Perceptions of Space

By changing an environment, some installation art attempts to alter our perspective of space. For instance, acclaimed artist James Turrell uses light, shadow, and architecture to distort a person’s impression of depth. He altered a space using carefully positioned LEDs into an all-encompassing encounter that enveloped the observer in what seemed like a living, and heavenly womb in his groundbreaking piece Breathing Light (2013) for the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

Olafur Eliasson’s The Weather Project (2003) brought the outside in by changing a space into an unsettling depiction of the sun using mono-frequency lights and fog.

Richard Serra is noted for his gigantic metal sculptural shapes that distort, pulsate, and dominate interior spaces in ways that disrupt the audience’s equilibrium and feeling of stability as they move into, across, and around the massive-scale works. These works appear to take viewers into other worlds, frequently evoking questions about life – the tangible, metaphysical, and spiritual.

Famous Installation Art Examples

Since installation art is particularly challenging to store and sell, this movement opposes art commercialization, challenging the usual processes used to evaluate the worth of pieces. Efforts to market installations have sparked concerns regarding the process of deconstructing and reconstructing work created for a specific place, and how this could potentially reduce the original significance and value. It has also sparked debate within the art and archive communities regarding whether a momentary piece should be replicated and distributed as the original, or if a non-permanent item should be recreated permanently to ensure its longevity.

Étant Donnés (1966) by Marcel Duchamp

| Artist | Marcel Duchamp (1887 – 1968) |

| Date | 1966 |

| Medium | Tableau |

| Location | The Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, United States |

This was one of the earliest works to create a precise and controlled viewing experience for spectators, which is still a fundamental principle of Installation art today. The art world was taken aback by Duchamp’s three-dimensional scene, since most assumed he had abandoned art over 25 years before this, his final work, was released. Viewing the work involved looking through peepholes in a wooden door to discover a reclining sculpture of a naked lady in front of a lushly painted landscape.

Duchamp coerced the audience into cooperation by creating a voyeurism encounter rather than merely presenting a typical nude artwork on the wall.

The Dinner Party (1979) by Judy Chicago

| Artist | Judy Chicago (1939 – Present) |

| Date | 1979 |

| Medium | Mixed Media |

| Location | Brooklyn Museum, New York City, United States |

This art installation, which has become a Feminist art symbol, consists of a big triangular table decorated as a traditional feast, with 39 table settings, each commemorating a significant woman. Each set includes embroidered runners, gilded dining cutlery, and porcelain plates that unashamedly mimic the vulva and change in theme depending on the recipient.

Virginia Woolf, Sacajawea, and the deity Kali are among those honored. Another 999 names are engraved in gold on the white floor underneath the dinner table.

Viewing the work becomes an experience in and of itself. She demonstrated the strength that was characteristic of Installation art by expressing her point through a three-dimensional, tangible item rather than a written declaration or painting.

Electronic Superhighway: Continental U.S., Alaska, Hawaii (1995) by Nam June Paik

| Artist | Nam June Paik (1932 – 2006) |

| Date | 1995 |

| Medium | Electronic communications equipment |

| Location | Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington DC, United States |

This work predicted the advent of what he dubbed an electronic information “superhighway” – which, remarkably, became a reality by the 1990s with the development of Internet access. Paik’s fascination with emerging technology led him to construct several massive, free-standing constructions out of TV screens, DVD players, cables, and other materials.

This type of multimedia experience is a prevalent motif in Installation art, enabling the Installation artist to demand the attention of the viewer in a direct, sensory-based manner.

For this installation, the artist assembled over 300 television screens in the configuration of a map of the United States, highlighted each state with brilliant neon lights, and played video snippets indicative of the state it represented on each screen.

The piece is a massive record of America’s cultural and physical features.

My Bed (1998) by Tracey Emin

| Artist | Tracey Emin (1963 – Present) |

| Date | 1998 |

| Medium | Mixed media |

| Location | The Duerckheim Collection |

Throughout the years, this exhibit has elicited as much criticism as it has received admiration. The installation was a literal personal portrayal: the consequence of multiple bedridden, depressed days in which Emin gathered rubbish around her bed, including used condoms, used underwear, and beverage containers.

Some have called the installation sculpture, which the artist created following a tragic marital collapse, self-absorbed and deluded, while others have called it pivotal and inspirational.

With its apparent realism, reviewers and admirers alike believe that it irrevocably changed the direction of Installation art. By showing her own bed as art, Emin advanced the movement’s goal of providing the observer with a more personal experience. The graphically narrative portrayal of Emin’s life at the time, along with its honest nature, generated an engrossing environment that suggested experience.

Members of the audience may either cringe in revulsion at the spectacle of personal depravity or retreat guiltily inward, knowing that we all have some dirty laundry.

Obliteration Room (2002) by Yayoi Kusama

| Artist | Yayoi Kusama (1929 – Present) |

| Date | 2002 |

| Medium | Stickers |

| Location | Queensland Art Gallery, South Brisbane, Australia |

It began as a normal room, one that was absolutely ordinary except for the fact that it had been fully painted over in white. Intrigued attendees were provided with a sheet of stickers manufactured to the artist’s specifications and then encouraged to apply the stickers wherever they pleased on the room’s blank canvas. Eventually, the surfaces became a burst of color, with countless stickers covering every conceivable surface.

Kusama took care to select a familiar setting that viewers would recognize, so that participants, particularly children, would freely engage with the piece.

The piece was her method of interacting with the surfaces of a space and extending some of the artistic processes to the spectators, integrating them fully in the creation of this interior. This dynamic project extended the tradition of active audience interaction in installation art by enabling them to co-create the piece.

It also allowed people to get completely absorbed in an experience that impacted the senses while remaining faithful to the artist’s distinct vision and style.

Rain Room (2012) by Random International

| Artist | Random International (est. 2005) |

| !Date | 2012 |

| Medium | Rain emulation |

| Location | Various museums |

Random International, a collaborative group, produced a completely immersive experience that toured several museums and architectural locations, consisting of a whole room drenched with rain. Visitors stood on the outskirts, barely illuminated from above, to take in the recreation of natural phenomena. When visitors walked into the rain, their body heat caused the rain to cease just in the areas where they were.

It was intended to provide a tranquil reprieve from daily life and to stimulate sensory thought on the interaction between man and environment.

It also gave spectators the ability to manipulate the rain. The piece’s goal was to raise questions about the human experience in a machine-led future. Rain Room exemplifies the fascinating modern intersection of imagination, science, and technology that is presently influencing cutting-edge installations that challenge our preconceived notions of art.

That wraps up our list of Installation art examples! As we have discovered, this genre was influenced by other forms of conceptual and performance art styles. Despite varying sources of inspiration, and varying methods of execution, the principal objective of most Installation artists was to use three-dimensional spaces to convey a message about our world by enabling guests to engage with the artwork.

Take a look at our art installations webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Installation Art?

Installation art usually occurs in an indoor space and involves materials that are arranged in a manner that imparts a message when keeping the entire space in mind. Instead of the qualities of a final product, the emphasis is frequently placed on the concept and its effect. Installation art is often a transient work of art, but its effect, statement, and underlying concept last forever. The perception of the viewer is meant to be altered, and engagement is encouraged.

Where Did Installation in Art Start?

The origins and foundations of installation art are sometimes connected with Conceptual art, dating back to artists such as Marcel Duchamp and his creative technique of exhibiting his readymade artworks, such as his much renowned (and hated) urinal installation. Other early inspirations that are said to have prepared the way for the development of installation art as a genre include avant-garde Dadaism shows, Spatialism ideas, and even certain works by John Cage. However, it was not until the 1970s that the word Installation was used to define artworks that include the viewer’s complete sensory experience.

Jordan Anthony is a Cape Town-based film photographer, curator, and arts writer. She holds a Bachelor of Art in Fine Arts from the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, where she explored themes like healing, identity, dreams, and intuitive creation in her Contemporary art practice. Jordan has collaborated with various local art institutions, including the KZNSA Gallery in Durban, the Turbine Art Fair, and the Wits Art Museum. Her photography focuses on abstract color manipulations, portraiture, candid shots, and urban landscapes. She’s intrigued by philosophy, memory, and esotericism, drawing inspiration from Surrealism, Fluxus, and ancient civilizations, as well as childhood influences and found objects. Jordan is working for artfilemagazine since 2022 and writes blog posts about art history and photography.

Learn more about Jordan Anthony and about us.

Cite this Article

Jordan, Anthony, “Installation Art – An Investigation of Art Installation Pieces.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. October 18, 2022. URL: https://artfilemagazine.com/installation-art/

Anthony, J. (2022, 18 October). Installation Art – An Investigation of Art Installation Pieces. artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. https://artfilemagazine.com/installation-art/

Anthony, Jordan. “Installation Art – An Investigation of Art Installation Pieces.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source, October 18, 2022. https://artfilemagazine.com/installation-art/.