Romanesque Art – Charlemagne’s Unifying Christian Style

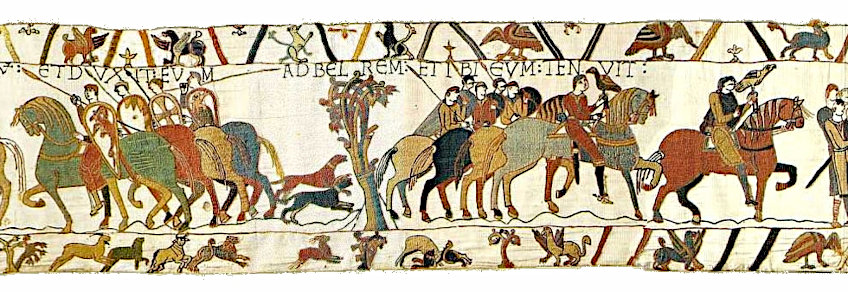

Romanesque art refers to the dominant art movement in Europe, following the Pre-Romanesque period, starting roughly around 1000 CE, or later in different regions. This appropriation of the building style of Constantine’s Christian Rome was begun by the architects of the first Holy Roman Emperor Charlemagne. Intended as a unifying gesture, the movement dominated European architecture up until the eventual rise of the Gothic movement around the 12th Century CE. The movement reached its peak around 1075 to 1125 CE, specifically in Britain, France, Italy, and Germany.

Contents

The Romanesque Art Movement

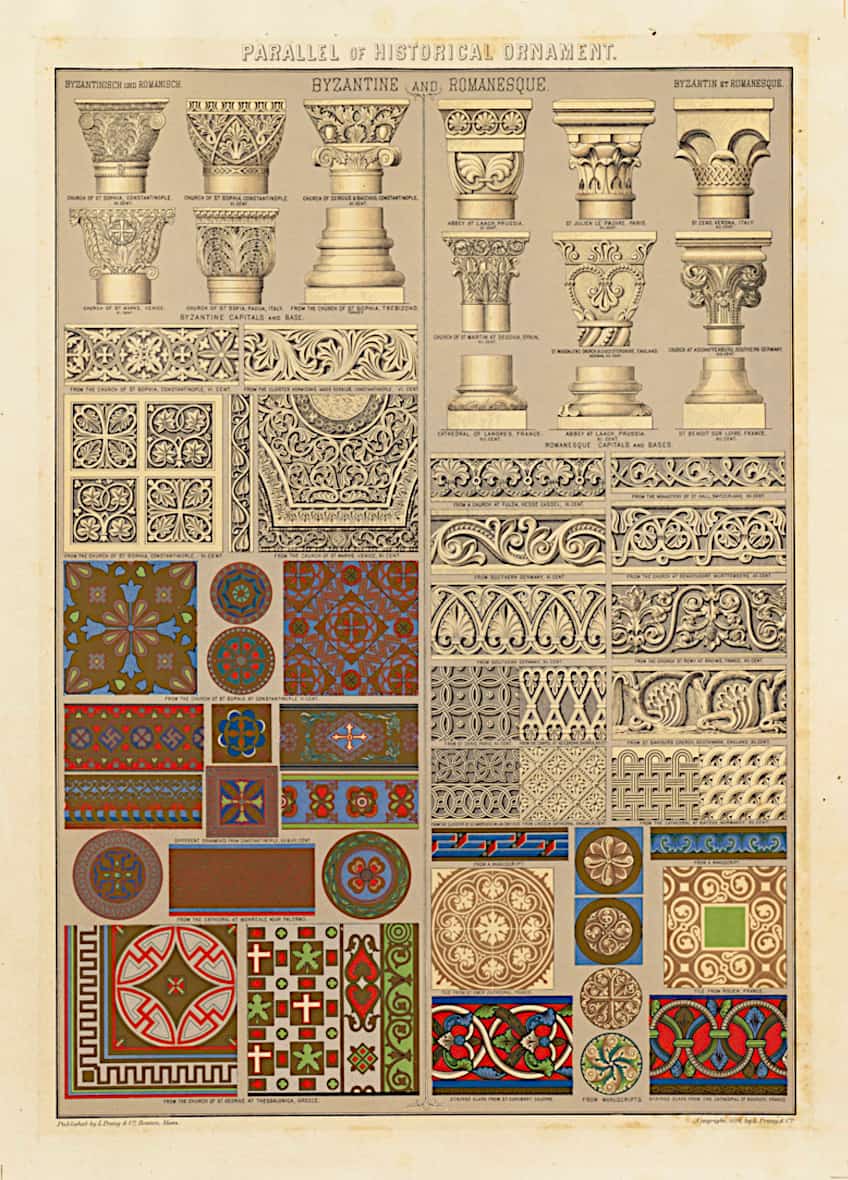

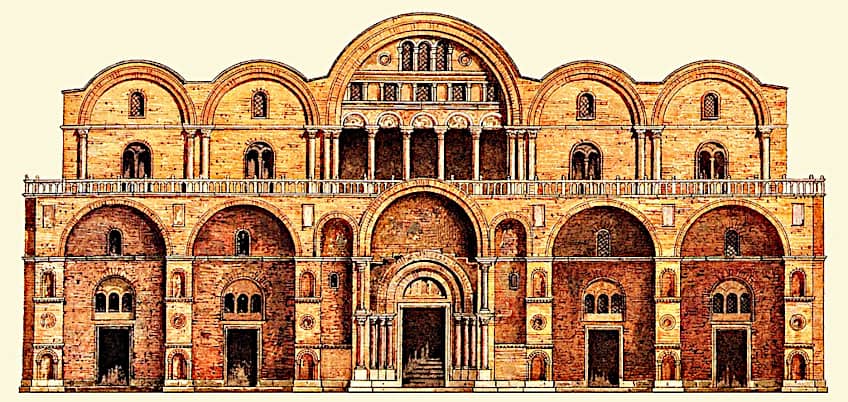

The term ‘Romanesque’ was created retroactively by art historians in the 19th century, specifically for Romanesque architecture, which featured many fundamental elements of the architectural style of Constantinian Rome. This can be seen in features such as the round-headed arches, as well as barrel vaults, apses, and acanthus-leaf decoration, but the movement also incorporated much of its own distinct features. It was inspired by the Carolingian style developed under the first Holy Roman Emperor Charlemagne, who sought to reflect the scope and grandeur of the Christian Roman Empire in his new European one. The term was coined as the movement involved the combination of Roman, Ottonian, Carolingian, Byzantine, and regional Germanic traditions and style.

Romanesque art was also heavily influenced by Byzantine art, as well as the anti-classical fervor of British Insular art. These components combined to create a very distinctive and coherent aesthetic. The style especially flourished in France, with some of the movement’s most significant advances made in the French region. The only parts of Europe the movement didn’t fully take off in were those areas in Eastern Europe that still had heavy Byzantine traditions and architecture.

There was architectural continuity with the Late Antique style in Southern France, Italy and Spain, but the Romanesque style was the first to take over all throughout Christian Europe. The movement has been described as the first pan-European style, spanning from the Mediterranean to Scandinavia, since the Imperial Roman style of architecture. The movement was spread through increased travel along the pilgrimage routes to holy places like Santiago de Compostela in Spain, or as a result of the crusades, which went through the Byzantine empire’s lands.

With this expansive reach, the movement naturally had several variations based on region, with Tuscan Romanesque art, for example, being rather different from Romanesque art found in the Northern regions of Europe. Interestingly, some historians believe that the Roman style was not very common in most parts of Europe, Roman architecture and construction techniques were not used in Scandinavia and were only used in official buildings in the northern countries. The exception was a number of magnificent Constantinian basilicas that were still standing in Rome and served as models for new construction.

Romanesque art refers to paintings and decorative arts as well as sculpture and architecture. During this period Europe saw steady economic growth, and only the royal court and a select group of monasteries could continue to produce art of the finest caliber. By the conclusion of the era, the majority of masons, goldsmiths, and painters fell under the category of lay artists, which gained in value.

History of the Movement

In the first decade of the eleventh century, The best quality art was no longer entirely restricted to the royal court and a small group of monasteries, as it had been during the Carolingian and Ottonian periods. Instead, Europe experienced a steady increase in prosperity. This was reflected in the architecture of the cities, with Radulfus Glaber, a Burgundian historian, noting a “white mantle of churches” rising over “all the earth.” This building boom persisted throughout the following two centuries, encouraged by economic prosperity, comparatively stable political conditions, and an increase in population. With the period’s expansionist new orders, the Cistercian, Cluniac, and Carthusian, which spread throughout Europe, monasteries remained to be of utmost importance.

To accommodate the increasing numbers of priests and monks as well as the increasing numbers of visitors who came to worship the saints’ relics, stone churches of previously unheard-of proportions were built such as the Sainte-Foy at Conques, France. When cathedrals and city churches have been restored, however, it is generally the churches in small towns and villages, those along pilgrimage routes, and those that were artistically painted to a very high quality that have survived. No true Romanesque royal palace exists today, but the Tower of London retains important stylistic elements.

The Role of the Church in the Romanesque Period

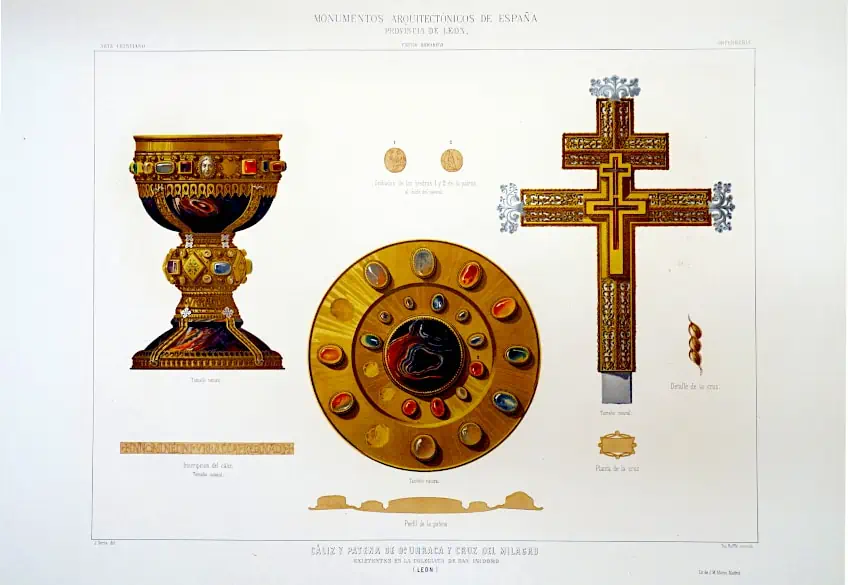

The churches on the pilgrimage route contained an ambulatory; a corridor allowing the faithful to stroll around the sanctuary, and a network of radiating chapels for many priests to recite Mass at once. These churches adopted the layout of the Roman basilica with a nave, lateral aisles, and alcove. The church façade, entrances, and capitals were adorned with massive sculpture. This was especially notable as these features had not been the standard practice since the fall of the Roman Empire. Bronze was used to create monumental doors, baptismal fonts, and candleholders that were frequently ornamented with scenes from biblical history.

This rise of churches and Christian/Catholic sites began with the coronation of Charlemagne on Christmas Day in 800 CE, with the Pope installing Charlemagne as Holy Roman emperor at St. Peter’s Basilica with the intention of restoring the former Roman Empire. Much of Europe was still ruled by Charlemagne’s political heirs, which encouraged the gradual formation of independent political states that were eventually united into countries through fealty or defeat.

As a result, the Holy Roman Empire was established by the Kingdom of Germany. This was then furthered with the conquest by William Duke of Normandy’s of England in 1066, with castles and churches being built to strengthen the Norman position. Several notable churches constructed at this time were erected as centers of temporal and spiritual authority or as sites of coronation and interment.

The spread of the religion throughout Europe was caused by the large-scale migration of the Crusades from 1095–1270 CE, which resulted in the spread of ideas and vocations. Through trade and the Crusades, in particular, the churches of Constantinople and Eastern Europe, usually including domed architecture, had a significant impact on the architecture of several villages and towns. St. Mark’s Basilica in Venice is the most famous example, but there are numerous other, lesser-known examples as well, including the church of Saint Front in Périgueux and the Angoulême Cathedral.

As previously stated, The non-professional artist, also known as the lay artist, was rising in stature; Nicholas of Verdun appears to have been well-known throughout the continent. By the conclusion of the era, lay painters like Master Hugo are considered to have been the majority, at least among those producing the highest quality of work. By this time, the majority of masons and goldsmiths were also laymen. Without a doubt, the iconography for their work work was dictated by the church.

Despite regional variances, the constant mobility of people, monarchs, lords, bishops, abbots, craftsmen, and peasants had a significant role in the development of the uniformity in building techniques, and this uniformity created a recognizable Romanesque style.

Romanesque Art Characteristics and Influences

Byzantine art, particularly in painting, and the anti-classical vigor of British Isles Insular art adornment had a significant influence on Romanesque art. These components combined to create a very distinctive and well-cohered aesthetic. Romanesque architecture had tremendous quality, thick walls, round arches, solid piers, groin vaults, towering towers, and symmetrical layouts, combining elements of Roman and Byzantine structures with other regional traditions. Romanesque sculpture, painting, tapestries, and decorative arts were done in an energetic manner.

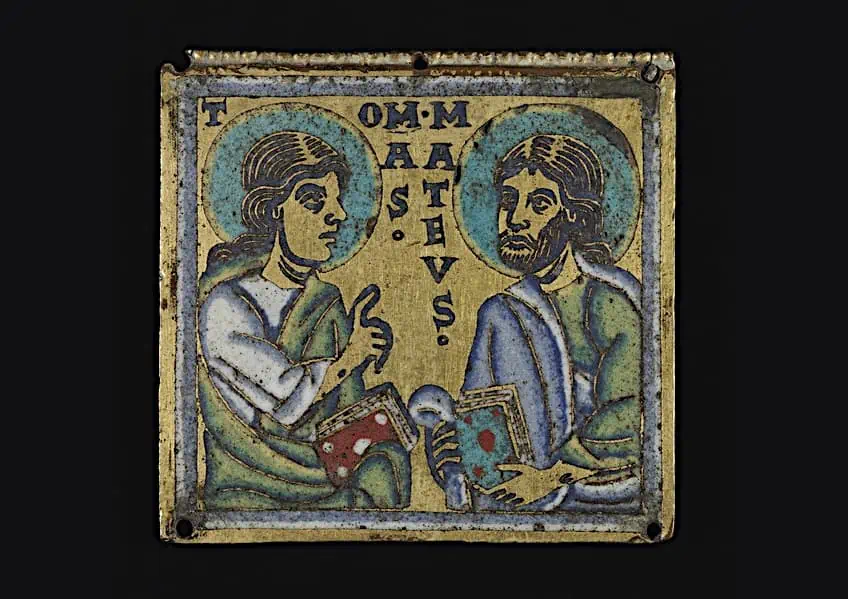

Influences

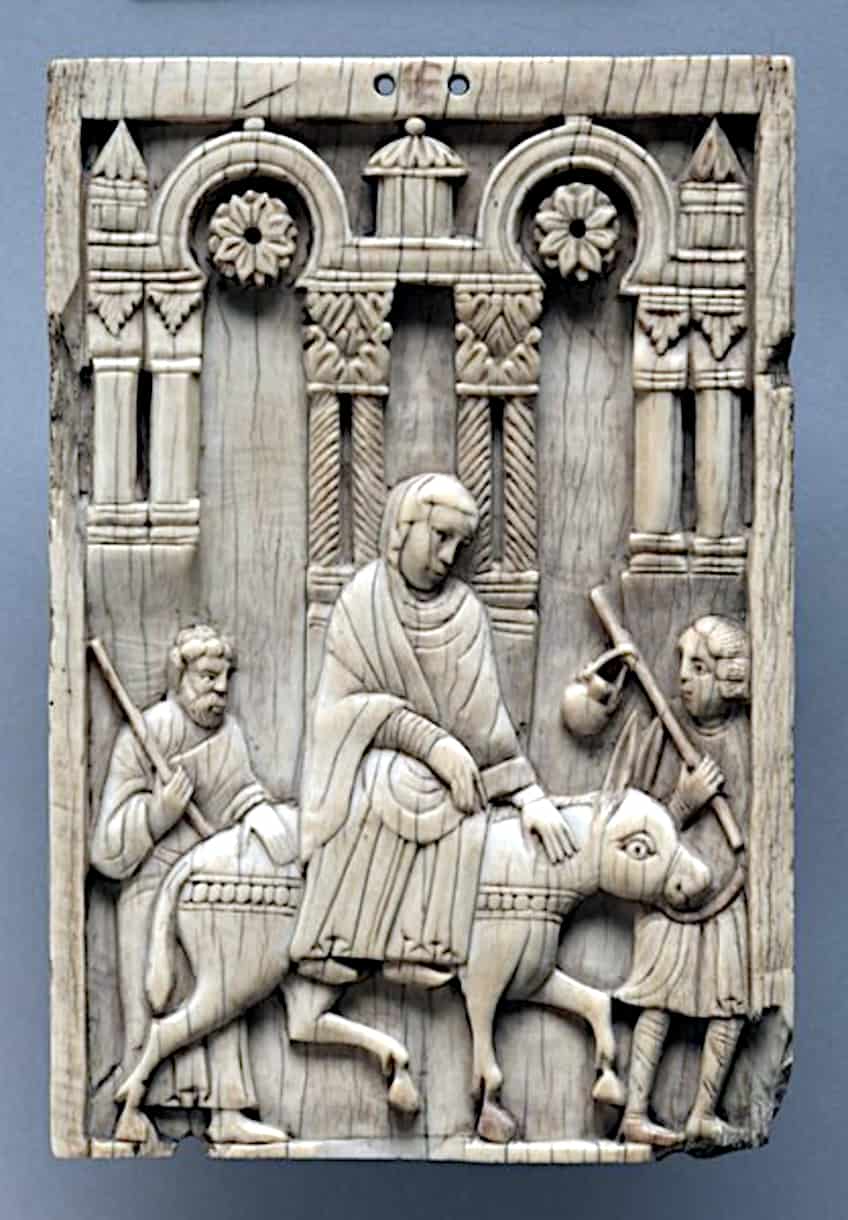

From the late eleventh century onward, Romanesque art also reflected Byzantine influences, by way of Italy. This can be seen in examples such as Plaque with the Crucifixion and the Defeat of Hades. (10th Century CE) This Byzantine artworks shows that certain aspects of Hellenistic art, such as a consistent modelling of the human form beneath drapery and a repertoire of gestures expressing emotions, had been retained by Byzantium but had vanished in the West. The ivory plaque depicting the Journey to Emmaus and the Noli Me Tangere, (1115 – 1120 CE) which was carved in northern Spain in the first half of the twelfth century, contains several components. The Romanesque artist, in contrast to the Byzantine sculptor, has given his composition a greater feeling of drama through a more forceful play of motions and swirling, pearl-bordered draperies. The Anglo-Saxon Square-Headed Brooch (500 – 600 CE) and the Initial V (1176 – 1195 CE) from a Bible, both illuminated at the end of the twelfth century in the Cistercian monastery of Pontigny in eastern France, show how long influences from Insular art persisted in the Romanesque movement.

Most significantly, Romanesque art developed a visual vocabulary that could express the principles of the Christian religion, which was more significant than its synthesis of many sources. The tympanum, on which the Last Judgment or other prophetic dramas could take place, was created by Romanesque architects as a somber prelude to the spiritual experience of entering the church. On doors, capitals, and walls inside the structure, the faithful came across other events from biblical history, and were drawn into the story by their lively, direct language, such as The Temptation of Christ by the Devil (1125 CE).

Themes

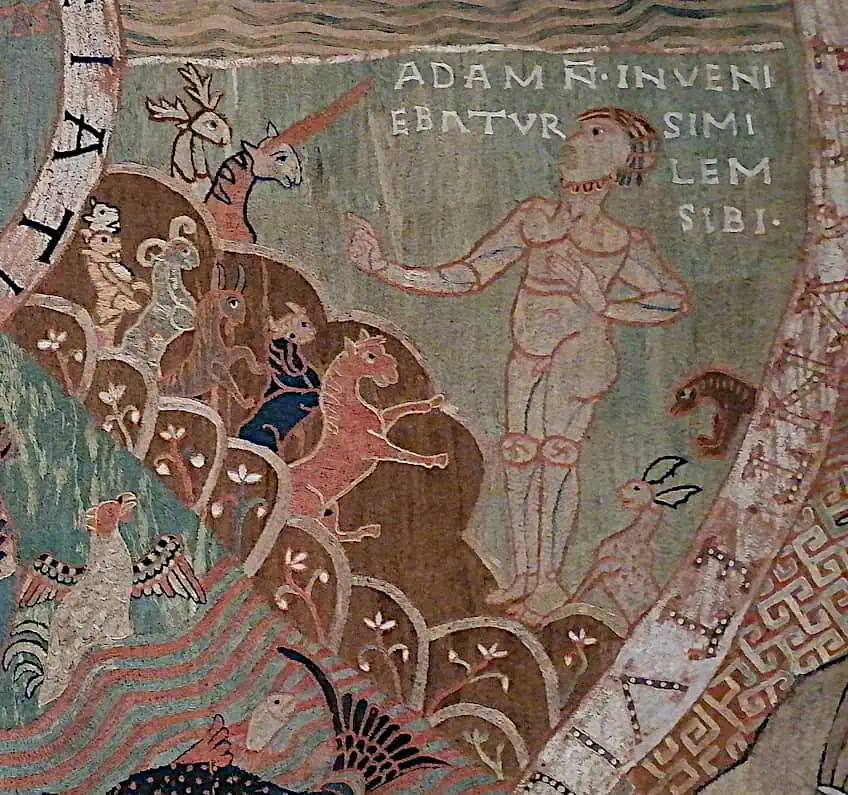

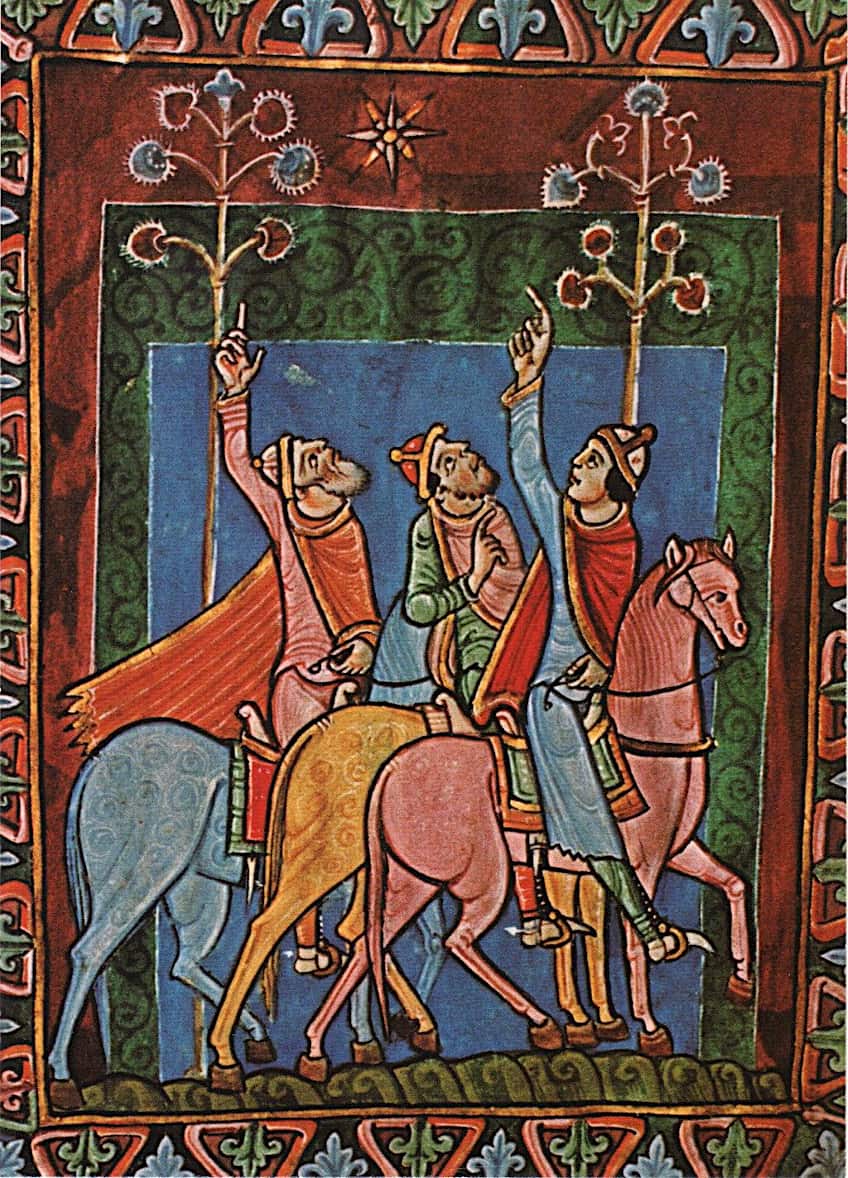

In addition to the Romanesque architecture, the sculpture and artwork of the time had a robust style. The most prevalent themes in churches were representation of Christ, as well as the Last Judgment, and scenes from the Life of Christ, and the latter continued to use fundamentally Byzantine iconographic models. As new scenes had to be created, more creativity could be found in illuminated manuscripts. The bibles and psalters of the time were the manuscripts with the most elaborate illustrations.

Characteristics

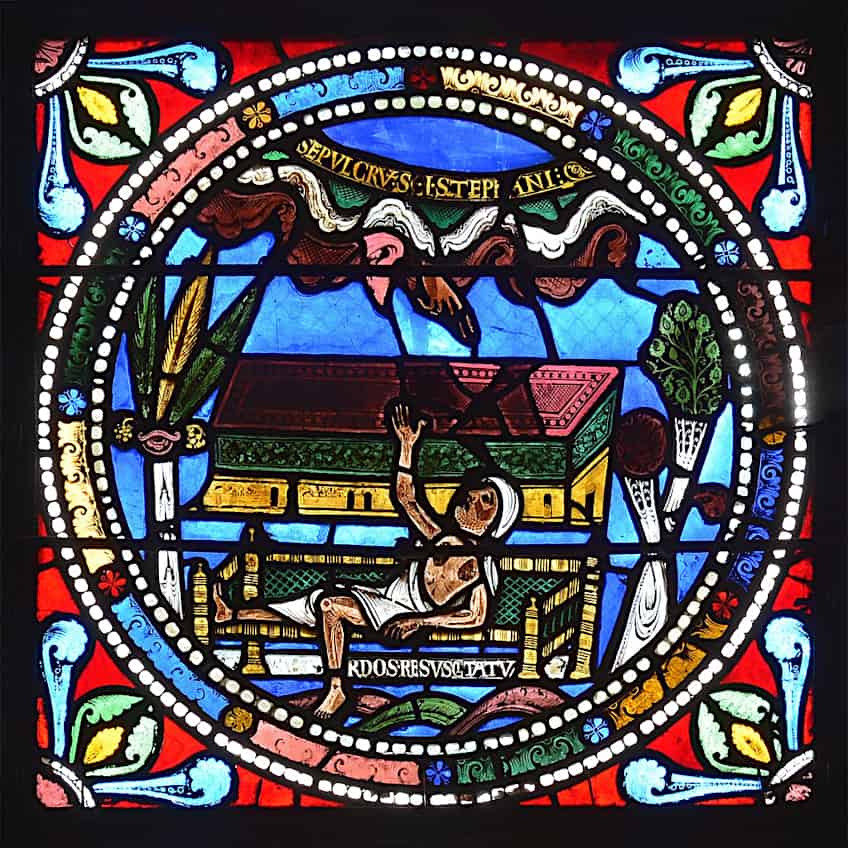

The majority of the colors were primary and quite stunning. These colors are only still visible in their former brightness in stained glass and a few exceptionally well-preserved texts in the twenty-first century. Although there are tragically not many survivors, stained glass became frequently used. Since there were no comparable Byzantine models, colossal designs, frequently Christ in Majesty or the Last Judgment, were carved onto the tympanums of significant church gates during this time period. These designs were treated more freely than painted equivalents.

In terms of composition, there was usually minimal depth, in an effort to make room for the shapes of historiated initials, column capitals, and church tympanums, which are common themes in Romanesque art. Figures often had varying sizes, based on their importance or cultural significance. When landscape backgrounds were attempted, they tended to resemble abstract decorations rather than realistic ones, as the trees in “Morgan Leaf.” Rarely did portraits exist.

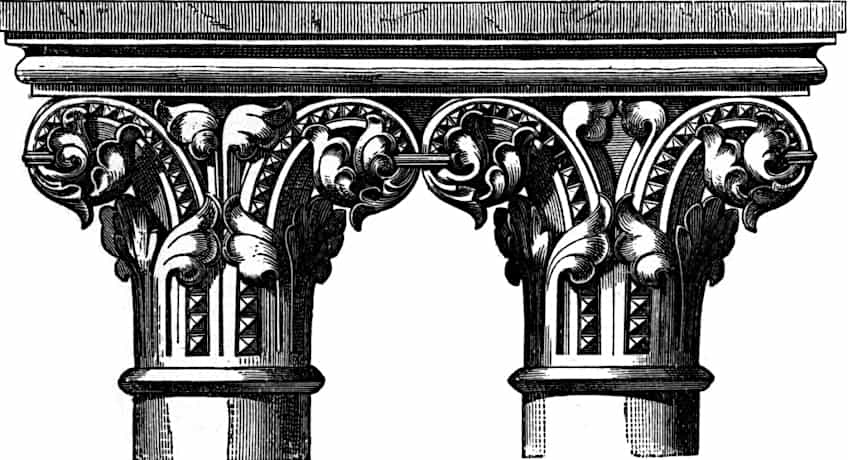

When it came to the architecture, the caps of columns were carved with the same inventiveness, frequently with settings that included multiple people. At the outset of the era, Germany introduced the huge wooden crucifix and free-standing statues of the seated Madonna. The predominant sculptural style of the time was high relief.

The majority of Romanesque sculpture was depictive of the biblical theme. Capitals featured a wide range of subject matter, such as scenarios from the Creation and Fall of Man, moments from the life of Christ, and scenes from the Old Testament that foreshadow his Death and Resurrection, like the stories of Daniel in the Lions’ Den, and Jonah with the Whale. Nativity scenes were common, with the Three Kings motif being especially well-liked. Fine examples that have been preserved in their entirety include the cloisters of Santo Domingo de Silos Abbey in Northern Spain, Moissac, and the relief sculptures on the numerous Tournai fonts found in churches in Southern England, France, and Belgium.

The extensive sculptural plan that fills the area around the gateway or, in some cases, a large portion of the facade, was a common characteristic of some Romanesque churches. In the wide recesses that the arcading of the front produced, the sculpture at the Angouleme Cathedral in France is extremely intricate. The door of the church of Santa Maria at Ripoll in Catalonia, Spain, is surrounded by an intricate low relief pictorial design. The sculptural designs were intended to send a message that a Christian believer should acknowledge wrongdoing, repent, and be reconciled. Reminding the believer to repent is the Last Judgment. The Crucifix, which is carved or painted and is prominently exhibited inside the church, serves to remind the sinner of redemption.

The sculptures frequently have ominous forms and themes. These pieces can be seen interwoven in the vegetation on door moldings, on capitals, corbels, and bosses. They symbolize shapes that are difficult to recognize in modern times. Exaggerated carvings of nude women, terrifying demons, ouroboros, which are ancient symbols depicting dragons or snakes swallowing their own tails in a circular form, and many other enigmatic monsters are frequent motifs. The original meaning of spirals and paired motifs in oral tradition has been lost or dismissed by contemporary researchers. Greed, gluttony, and lust are among the Seven Deadly Sins that were frequently depicted. Both the numerous individuals depicted with protruding tongues and the sight of many figures with large genitalia, which are a feature of the gateway of Lincoln Cathedral, might be associated with carnal vice.

The image of pulling your own beard was a sign of masturbation, while pulling your mouth wide open was considered a sign of obscenity. The subject of a tongue poker or beard stroker being punished by his wife or being captured by demons is frequently seen on capitals from this era. These can be seen in the interior corbels of Poitiers Cathedral in France. Another common theme is the conflict between demons vying for the soul of a miser or other offender.

Romanesque Paintings

One of the mediums that expressed the Romanesque style was paintings and manuscript illuminations. Romanesque paintings in churches continued to use Byzantine iconographic models. The Last Judgment, Christ in Majesty, and scenes from His Life continued to be the most popular representations of this medium. The most ornately decorated examples of the era in illuminated manuscripts were bibles or psalters. More creativity grew as more scenes were depicted. They employed highly saturated primary colors, which are today only found in stained glass and well-preserved manuscripts in their original brightness. Despite the fact that there aren’t many surviving examples, this was the time when stained glass first became widely used.

Since they were only allowed to fill the tiny spaces of church tympanums, column capitals, and historiated initials, pictorial compositions typically lacked depth. The Romanesque definition of art frequently explored the tension between a constrained frame and a composition that occasionally veers outside of its assigned area. Figures were frequently depicted in a variety of sizes according to their significance, while landscape backgrounds were either lacking or more akin to abstract decorations than realistic ones, as seen in the “Morgan Leaf” trees. To fit the shape offered, human bodies were frequently stretched and twisted, and at times they even gave the impression of floating in space. These figures emphasized hair and drapery folds in addition to linear elements.

The early Romanesque illuminated manuscript brought together a number of schools within Western Europe: the “Channel school” of England and Northern France was greatly influenced by late Anglo-Saxon art, while the style in Southern France came more from an Iberian influence, and in Germany and the Low Lands (coastal region in North-western Europe), Ottonian styles continued to spread. Ottonian styles also had an impact on Italy along with Byzantine styles. By the 12th century, all of these were influencing one another, though naturally, regional uniqueness persisted.

Romanesque illumination was mostly used for decorating pages of sacred texts, which included large decorative initials at the beginning of each book. This can also be seen specifically in the Book of Psalms, where major initials were similarly illuminated. In both situations, more extravagant examples can include scenes in compartments, often with multiple scenes per page, in cycles on completely illuminated pages. The Bibles in particular frequently had and could be divided into multiple volumes.

The Journey of the Magi (1130 CE) by Unknown

| Artist | Unknown |

| Date | 1130 CE |

| Medium | Tempera and Gold on Parchment |

| Current Location | The J. Paul Getty Museum, California, United States |

Examples include the Winchester Bible, St. Albans Book of Psalms, as well as that of the Hunterian, the Fécamp Bible, Parc Abbey Bible, and Stavelot Bible. By the end of the century, lay commercial workshops of scribes and artists had grown in importance, and both laypeople and clergy had more access to illumination and books in general. An example of the artworks included in these bibles would be The Journey of the Magi, (1130 CE) depicting the three biblical magi, or three wise men, spotting the Star of Bethlehem. This artwork also features the aforementioned “morgan leaf” symbol.

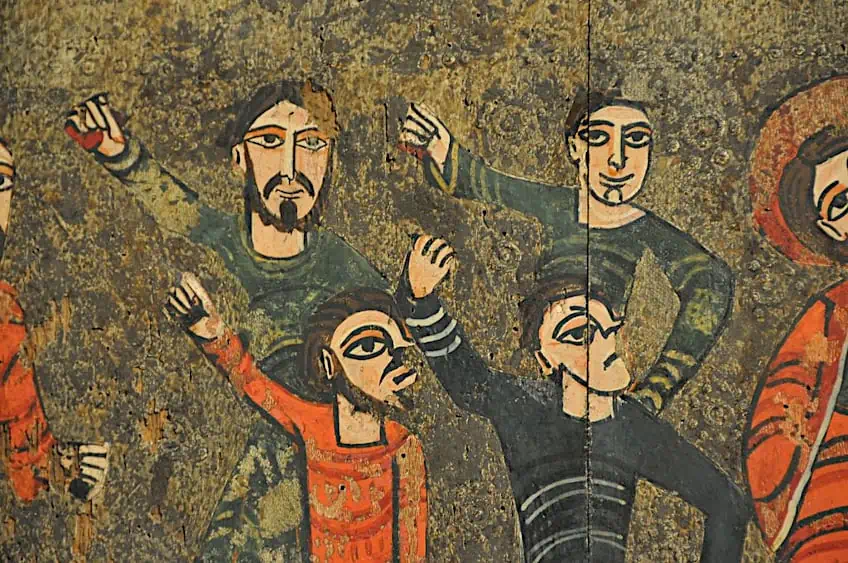

Another medium these paintings took the form of was wall paintings. Romanesque architecture’s broad wall surfaces and simple, curved vaults were ideal for mural decoration. Unfortunately, many of these antique wall paintings have been ruined by dampness or have been painted over when the walls were re-plastered. During periods of Reformation iconoclasm, such images were methodically removed or bleached in England, France, and the Netherlands.

Many of these works have been restored in places like Denmark, Sweden, and other countries. Early in the 20th century in Catalonia, Spain, there was a push to rescue such murals by taking them and bringing them to Barcelona for protection. This resulted in the magnificent collection at the National Art Museum of Catalonia. They have suffered from conflict, neglect, and alterations in fashion in other nations.

Romanesque Wall Paintings

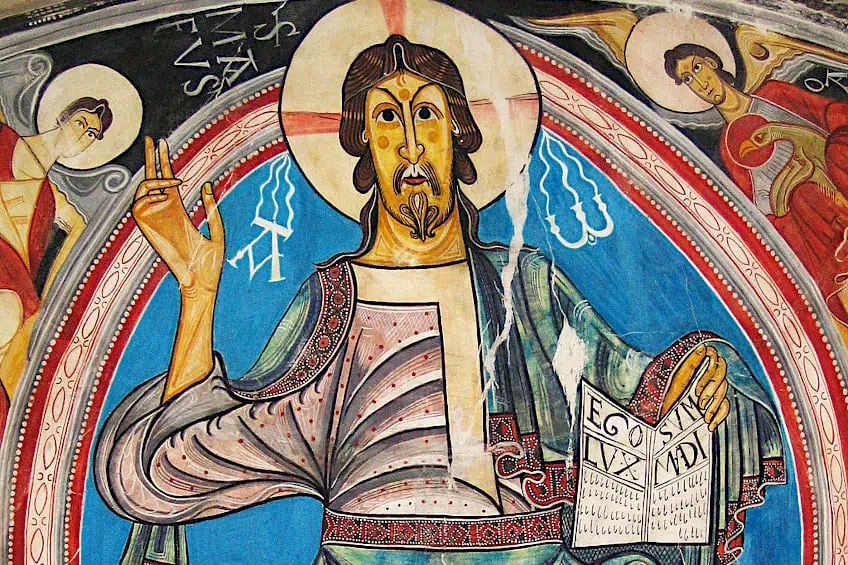

Another common medium of the Romanesque movement was that of wall paintings; a traditional design for the full painted decoration of a church, derived from earlier eras that were frequently in mosaic. These paintings often featured Christian imagery, such as Christ in Majesty or Christ the Redeemer as its focal point in the semi-dome of the alcove, (this would sometimes be the Virgin Mary if that specific church was dedicated to her) enthroned within a mandorla and framed by the four winged creatures, which were symbolic of the Four Evangelists.

There is a clear resemblance between this design and examples from the gilt covers or the illuminations of Gospel Books of the time. This resemblance can be demonstrated in the Apse of Sant Climent (1123 CE).

Apse of Sant Climent (1123 CE) by Master of Taüll

| Artist | Master of Taüll |

| Date | 1123 CE |

| Medium | Fresco |

| Current Location | National Museum of Art, Barcelona, Spain |

The beauty of this artwork resides in the way it presents Christ on Judgement Day by fusing components from many Biblical visions (Revelation, Isaiah, and Ezekiel). Christ’s appearance from the background causes the composition’s center to travel outward, under the direction of the decorative sense of the outlines and the deft use of color to create volume. Picasso and Francis Picabia, two 20th-century avant-garde artists, were intrigued by this work’s extraordinary qualities and graphic power, which reached out to modernity.

The halo on Christ’s head is a representation of divinity, while the round area beneath his feet is a representation of the earth. Christ holds a book with the words EGO SUM LUX MUNDI, which translates to “I am the light of the world,” in his left hand, which stands for benediction. The beginning and the end are represented by the Greek symbols of Alpha and Omega that hang on either side of the Christ figure. Four evangelists are represented by the fourfold illustrations.

To the right of Christ, an angel may be seen next to the lion clutching one of its rear legs, which is a representation of St. Mark. St. Luke is represented to the left by an angel grasping a bull’s tail. In the triangle-shaped area on either side of the mandorla, the other two evangelists can be seen. St. Matthew is represented by an angel holding the Gospel Book, and St. John is represented by another angel holding an eagle in his arms. The Virgin Mary, St. Thomas, St. Bartholomew, St. John the Apostle, St. James, and San Felipe are depicted beneath the mural painting of Christ in the mandorla. Red rays emanating from a dish that the Virgin Mary is holding signify the blood of Christ.

The fresco, from which the unidentified Master of Taüll gets his name, is one of the greatest works of European Romanesque art. It was painted at the Sant Climent de Taüll church in the Vall de Bo, Alta Ribagorça, Catalan Pyrenees, during the beginning of the 12th century. The church’s apse was covered by the artwork. It was transported to Barcelona between 1919 and 1923, together with other pieces of the fresco artwork, in an effort to conserve the paintings in a stable, secure museum setting.

Romanesque Architecture

The practice of creating massive stone sculptures and bronze statues was effectively abandoned with the fall of the Western Roman Empire, just as it was in the Byzantine (Eastern Roman) world (for religious reasons). Evidently, some plaster or stucco life-size sculpture was produced, although surviving examples are understandably scarce. The life-size wooden Crucifix that Archbishop Gero of Cologne ordered in between 960 and 965 is the most well-known surviving major sculpture from Proto-Romanesque Europe. This piece is thought to be the forerunner of a style that later gained popularity. From the twelfth century, these were later placed on a beam beneath the chancel arch, known in English as a rood, with statues of the Mother of God and John the Evangelist to the sides.

Figurative sculpture saw a significant renaissance in the 11th and 12th centuries, and architectural reliefs were a defining feature of the later Romanesque era. Two more sources, in particular text illumination and miniature sculpture made of ivory and metal, served as the foundation for figurative sculpture. Another possible influence is the enormous carved strips, known as friezes, sculpted on Armenian and Syriac churches. Together, these influences gave rise to a distinct aesthetic that is recognizable throughout Europe, while the most impressive sculptures are mostly found in Italy, Spain, and the north of France.

Romanesque churches specifically were characterized by semi-circular arches for windows, doors, and arcades; barrel or groin vaults to support the roof of the nave; large piers and walls, with minimal windows, to hold the outward thrust of the vaults. Along with a tower over the intersection of the nave and transept, side aisles with galleries above the vaults, and smaller towers at the western end of the church structure were also present. French churches frequently incorporated radiating chapels to house additional priests, ambulatories surrounding the sanctuary apse for passing pilgrims, and substantial transepts between the sanctuary and nave as extensions of the early Christian basilica design.

The First Romanesque style of architecture, often referred to as Lombard Romanesque architecture, was distinguished by strong walls, a dearth of sculpture, and the presence of rhythmic decorative arches known as Lombard bands. The level of technical skill used in constructing determines the distinction between the First Romanesque and Later Romanesque styles. The Romanesque style was characterized by a more refined style, increased use of the vault, and dressed stone, whereas the first Romanesque made use of rubble walls, smaller windows, and un-vaulted roofs. Abott Oliba, for instance, commissioned an addition to the Monastery of Santa Maria de Ripoll in 1032 that mirrored First Romanesque features such as two frontal towers, a nave with seven alcoves, and Lombard adornments such as blind arches and vertical strips.

While Romanesque architecture frequently possessed a few distinctive common elements, these frequently differed from place to place in terms of look and construction materials. Both religious and secular Romanesque architecture provide an overall sense of enormous firmness and strength. Instead of employing arches, columns, vaults, or other systems to support the weight of the structure, Romanesque architecture relies on its walls, or parts of walls known as piers, to do so. With the grand size of the walls, these appear strong and sturdy. The inclusion of arcades, columns, vaults, roofs, and arches and openings was another characteristic of Romanesque architecture. Despite the fact that these elements were common, Romanesque architecture has many ways of displaying them.

Illustration of Romanesque capitals, from Limburg by William Henry Goodyear, A History of Art: For Classes, Art-Students, and Tourists in Europe, A. S. Barnes & Company, New York, 1889; See page for author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

A notably well-known example of Romanesque architecture would be the Leaning Tower of Pisa (1372 CE) This Italian landmark and tourist attraction is a freestanding bell tower of the Pisa Cathedral. Along with its Romanesque architecture, the tower is most recognized for its four-degree lean. The tower stands at about 55.8 meters at its lower peak, and 56.4 meters at the higher peak.

The Leaning Tower of Pisa (1372 CE) by Diotisalvi and Guglielmo

| Artist | Diotisalvi and Guglielmo |

| Date | 1372 CE |

| Medium | Marble and stone tower |

| Current Location | Pisa, Italy |

The north-facing staircase has around 296 steps and the ground floor is filled with columns that echo the Greco-Roman classical style, with Corinthian capitals. The tower also includes some features of the Gothic style of architecture, and has seven bells for each note on the music scale. What makes this tower so recognizable, its signature ‘lean’ began in the 12th Century CE during the construction as a result of the unstable foundations and the softness of the land it was being built upon. The tower was built to be stable despite the lean however, and these efforts reduced the lean from 5.5 degrees to 3.97 degrees.

Other well-known examples of structures with Romanesque architecture include The Pisa Cathedral, (1092 CE) Cluny Abbey (910 CE) and the Basilica of Saint-Sernin. (1080 – 1120 CE)

Romanesque art developed a visual vocabulary that could express the principles of the Christian religion, as the socio-economic state of Europe had begun moving towards the religion on a dominant scale, which was more significant than its combination of many sources. The tympanum, on which the Last Judgment or other prophesied dramas from biblical texts could take place, was created by Romanesque architects as a somber prelude to the spiritual experience of entering the church. On doors, capitals, and walls inside the structure, the faithful came across other events from biblical history, and were drawn into the story by their lively, direct language. The movement was visible in not only paintings, but through architecture and sculptures.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Defines Romanesque Architecture?

The Romanesque period of architecture has tremendous quality, thick walls, round arches, solid piers, groin vaults, towering towers, and symmetrical layouts, combining elements of Roman and Byzantine structures with other regional traditions. Both the painting and the sculpture of the time were done in an energetic manner.

What Is the Romanesque Definition of Art?

The name “Romanesque” was coined by art historians in the 19th century to refer specifically to an architectural and decorative style of the Middle Ages, which echoed many fundamental elements of Christian Roman architecture. This included semi-circular arches, but maintained distinct regional characteristics.

What Are the Characteristics of Romanesque Style?

Romanesque buildings are distinguished by their tall and round arches, substantial stone and brickwork, small windows, sturdy walls, and their inclination to house works of art and sculpture that reflect biblical scenes. Romanesque art characteristics included the subject matter of Christianity, primary colors and minimal depth within the composition.

What Is an Example of Romanesque Art?

Romanesque art can be found in examples like Apse of Sant Climent (1123 CE). The church is typical of the attractive stone-built churches that sprang up in this area during the Romanesque period and is located in a lonely valley in northern Catalonia (northeast Spain today). Examples of Romanesque paintings include The Temptation of Christ by the Devil (1125 CE) and The Journey of the Magi (1130 CE).

What Influenced the Romanesque Style?

The Romanesque period of art involved significant influence from the growth and spread of Christian monasticism across Europe, with Christian themes making up almost all of the subject matter. Romanesque architecture was primarily influenced by the art and architecture of the Late Christianized Roman Empire, as well as elements of Islamic and Byzantine art.

Jordan Anthony is a Cape Town-based film photographer, curator, and arts writer. She holds a Bachelor of Art in Fine Arts from the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, where she explored themes like healing, identity, dreams, and intuitive creation in her Contemporary art practice. Jordan has collaborated with various local art institutions, including the KZNSA Gallery in Durban, the Turbine Art Fair, and the Wits Art Museum. Her photography focuses on abstract color manipulations, portraiture, candid shots, and urban landscapes. She’s intrigued by philosophy, memory, and esotericism, drawing inspiration from Surrealism, Fluxus, and ancient civilizations, as well as childhood influences and found objects. Jordan is working for artfilemagazine since 2022 and writes blog posts about art history and photography.

Learn more about Jordan Anthony and about us.

Cite this Article

Jordan, Anthony, “Romanesque Art – Charlemagne’s Unifying Christian Style.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. February 16, 2023. URL: https://artfilemagazine.com/romanesque-art/

Anthony, J. (2023, 16 February). Romanesque Art – Charlemagne’s Unifying Christian Style. artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. https://artfilemagazine.com/romanesque-art/

Anthony, Jordan. “Romanesque Art – Charlemagne’s Unifying Christian Style.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source, February 16, 2023. https://artfilemagazine.com/romanesque-art/.