Sumerian Art – Explore the Important History of Sumer Art

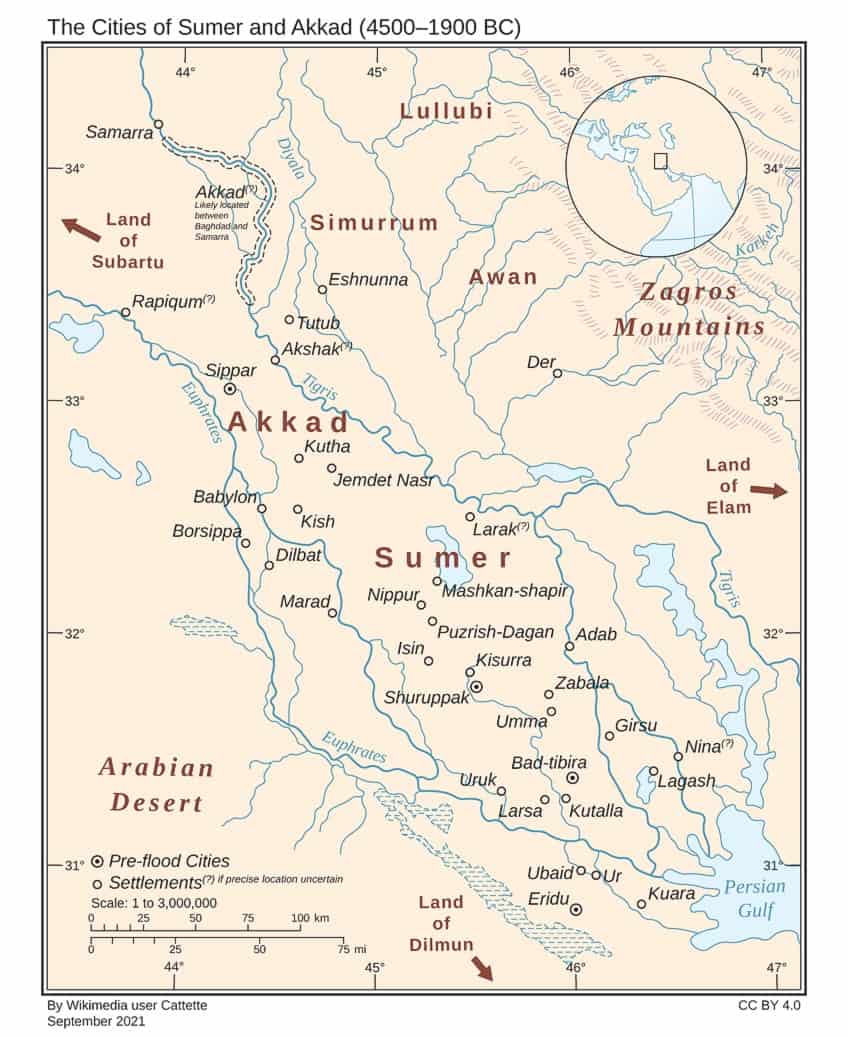

Sumerian art was created by the people of Sumer, a civilization that arose around 4000 BCE in Southern Mesopotamia. Sumerian civilization was one of the first advanced cultures of our species and was responsible for producing innovative Sumer artworks. The Sumerians’ architecture was also renowned for its incredible designs, such as the ziggurats at Ur. In this article, we will learn about the history of Sumerian art, and explore important examples of Sumerian statues, Sumerian carvings, and Sumer paintings.

The History of Sumerian Art

Sumer was the origin of Antiquity’s oldest art. The Sumerians were the first community to settle in southern Mesopotamia, draining the wetlands for cultivation, developing trade, and producing new types of pottery, as well as crafts like leatherwork, weaving, and metallurgy. These later stages of Neolithic artwork benefited immensely from the increase in population that followed from Sumerian life’s steady agricultural supply and established lifestyle.

Because of their sophisticated laws, technologies, and advanced Sumer art, Sumerian civilization outpaced all other cultures in the area at the time, even Egyptian culture.

Only ancient Anatolian locations from the Mesolithic age, such as Gobekli Tepe, may be considered to have produced earlier indications of substantial culture. The Sumerian civilization flourished in the fourth and third millennia BCE before being conquered around 2270 BCE. by Semitic-speaking Akkadian rulers. In essence, Sumerian art only really specialized in pottery until around 3500 BCE, yet it was of a grade considerably better than any type of Greek pottery made up to that date.

Following that, we can see the rise of free-standing Sumerian statues, as well as rudimentary bronze statuettes, basic varieties of personal jewelry, and beautiful motifs on several artifacts. During the Third Millennium, indications of complex bronze and copper casting processes emerge, with some bronze sculptures manufactured using the complicated cire-perdue technique. Excavations in Ur have uncovered a wealth of luxurious tombs bearing silver, gold, lapis lazuli, and ornate shell artifacts, as well as game boards, musical instruments, swords, and cylinder seals.

The intellectual classes started to utilize clay relief sculpture tablets to tell stories.

Sumerian Culture Characteristics

The Sumerian people are no longer thought to be the region’s first residents, but rather “occupiers,” but it is still unclear where exactly they came from and who they replaced. They seem to have been dominant at the beginning of recorded history, bringing the area’s first and most enduring written languages, improving knowledge and skills about metallurgy before their neighbors, creating the potter’s wheel, and making groundbreaking advances in a public organization, military tactics, legislation, and the Sumer arts.

It’s probable they arrived from the Iranian Plateau to the east, carrying these accomplishments with them from some yet-undiscovered Scythian or Persian cultural home.

The Sumerian Arts

According to Sumerian legend, the settlements of Sumer were founded by a civilization of hybrid fish-men who emerged from the Persian Gulf under the command of Oannes; and “all things that produce the regeneration of life were bestowed to humanity by Oannes, and no further creations have been produced since that moment.”

And this mythology only highlights the advances that current historians consider to be the most important in the evolution of man: the use of metallurgy, agriculture, and a written language.

These advancements are thought to have occurred simultaneously, as part of a single push of human intellect, and the oldest datable indications of them may be discovered in Sumer. Archaeological digs at Tepe Gawra in 1937 revealed the foundational walls of a “pre-Sumerian” ancient city dating before 4000 BCE, as well as relics suggesting that the “Painted Pottery Individuals,” long thought to be primitive except for their competence for creating ceramic artwork, enjoyed a developed and stable civilization.

There is also an indication of designed community construction, the first goldsmithing, and consequently the area’s jewelry art that can be dated, and a vessel featuring the first landscape artwork – all credited to a period half a century before the date initially recognized as the dawn of civilized art and history.

Sumerian civilization, which was previously thought to be on the same level as late Prehistoric art, is now recognized to have held many of the cultural characteristics often affiliated with later Egyptian civilization, among others.

Sumerian Architecture

The Sumerians were utilizing primitive vaults and arches around 3000 years before Roman architecture left its imprint over Europe, yet the remains are too fragmented to enable any sort of extensive discussion about the looks of monumental or household structures.

Because the Tigris-Euphrates plains lacked both wood and stone, the most frequent construction material was brick made from clay, and the architectural styles were probably basic and blocklike, as was typical of early brick constructions.

The temple tower, probably an artificial alternative for the hilltop from which the deities had been venerated, appears to have been the oldest characteristic of monumental structure, and it may have been the predecessor of the Moslem domes and minarets, the Assyrian ziggurats, and Christian steeples.

The ziggurat in Ur, like later ones in Assyria and Babylon, was built in gradually smaller levels, with an altar at the summit. Ramps were primarily used to gain access from the ground below.

The structure was a formed hill with no chambers except for the temple on top, like a stepped pyramid. Archaeologists have also uncovered several elevated houses with buttressed walls in Sumer. These buttresses, which were both structural and aesthetic, were a common characteristic of Sumerian architecture.

Sumerian Carvings and Reliefs

Low relief sculpture was popularly utilized on building walls and as adornment on elegant furnishings in materials other than stone, and standalone tablet monuments increasingly became commonplace. Because only a few locations have been unearthed so far – the most significant being Ur, Eridu, Lagash, Kish, and Nippur – the world’s untold riches of Sumerian carvings are likely to grow considerably; however, from the instances that have been discovered, one could already form an image of civilizations that enjoyed sophisticated workmanship in stone, metals, and shells, as well as colorful ornaments and elaborate patterns.

The pieces of art referred to as early Sumerian – such as the Tablet of Ur-Nina – were created before 3000 BCE and are not of the highest quality and don’t possess the usual level of craftsmanship.

The frieze of images of animals and men, consisting of limestone reliefs set into dark panels mounted to the temple wall at al Ubaid, is incredibly impressive and compellingly decorative. The exterior facade appears to have been elaborately embellished with mosaic artwork and stone sculptures.

There were numerous copper reliefs, such as a massive panel over the door representing two stags and a lion-headed eagle, as well as specimens of terracotta sculptures and fragments of many of the limestone friezes. A series of oxen, fashioned of hammered sheets of copper over wood, was arranged around a ledge underneath these relief elements. The structure dates from the mid-31st century BCE.

While massive works from previous periods are few, there is evidence that this art was preceded by a long stretch of time of accomplished carving and drawing.

The shell plaques fastened to musical instruments, and furnishings show extremely vibrant patterns, with images that are both distinctive and cleverly standardized for symbolic effect. These are often sculpted in low relief on a contrasting backdrop. There are other patterns composed of shell squares with energetic linear motifs engraved or carved. To make the design stand out clear and sharp, the lines were inlaid with a red or occasionally black paste, a technique replicated 40 centuries later in European niello art.

Sumerian Statues

There are in-the-round statues from the true Sumerian era that display an ability for the full-sculptural media, but nothing compares to the grandeur and exquisite aesthetic expression of representational Egyptian sculpture from the Old Kingdom period. There seems to have been minimal change in the traditions of the art from the 21st century BCE down to the period of King Gudea, about the 25th century BCE, and no significant progress in competence.

Some of King Gudea’s later full-length sculptures are huge, skillfully refined, and reposeful, but they lack the underlying sculptural vitality, the plastic eloquence, that defines contemporary Nile rock carvings.

Sumerian Decorative Arts

A distinct brilliance is reached in the realm of figurines, particularly when dealing with animals. There is, for instance, a donkey figurine fastened as a figurehead to the rein-guide on the saddle of Queen Shub-ad’s chariot donkeys. It’s a nice piece of realistic sculpting, with sharp observation yet with due respect to the figure’s purpose and placement. Bulls’ heads in copper and silver are also visually pleasing. Some of these were lyre embellishments and should not be evaluated separately. However, the qualities are such that the pieces retain their potency even when removed from their original context.

Our present understanding of Queen Shub-ad’s bulls’ heads, as well as the shell plaques, is all due to a single rich discovery at Ur, and their conservation and preservation are the results of an early human civilization tradition.

According to First Dynasty customs, when the queen passed in 3100 BCE, a significant proportion of her ladies-in-waiting were buried in her catacomb in the royal cemetery, to provide her whatever help and comforts she required in the hereafter. Earthly valuables such as the queen’s harps, chariot, and toilet goods were all walled in with them.

The art of headdresses, jewelry, gold utensils, and sculptures, in general, is characterized by extreme adornment and a lack of judgment in converting observed natural detail to artistic purposes. It is, in truth, a decadent style of art, from a period when the capacity to express attractively, characteristic of so many ancient peoples, had deteriorated into florid excess and a drive for accurate depiction for its own sake. Some of the uncovered chaplets resemble flowery wreaths that have been replicated directly from nature in gold and other precious metals.

Each leaf is accurate to its botanical model, and every vein is visible. Art is no more about an invention or selective adaptation, but rather about imitating natural beauty.

Cylindrical Seals

The sculpturing of cylindrical seals was a Sumerian miniature art that was to be passed down through the Assyrian-Babylonian dynasty. In Mesopotamia, writing was executed on wet clay slabs that solidified into permanent tablets. Because of the durable nature of these tablet records, the 20th-century world learned much about Sumerian literature and life.

The powerful dignitaries carried a personalized seal, which was often ornate, to sign or stamp the clay with their insignia.

Every Babylonian carried a seal and a stick carved into the shape of a rose, a flower, a bird, or a comparable design on the top. A tiny cylinder was carved as a “negative,” so that the imprint in the clay emerged as a relief. It generally displayed a figure design and was frequently a symbol of the owner’s dedication to a particular god.

Thousands of cylinder seals have been discovered, as have several clay artifacts bearing their imprints.

There are basic pictographic texts as well as vaguely geometrical motifs or solar imagery in the early instances. Just after 3500 BCE, the figured seals started to exhibit remarkable competence in relief depiction as well as a strong sense of stylization. There is a crispness, a precise delineation of distinct characters against uncomplicated backgrounds that is very appropriate for this wonderful work.

Notable Examples of Sumerian Art

Now that we have explored the history of Sumer art, we can look at a few notable examples of Sumerian statues, Sumerian carvings, and the Sumerians’ architecture. These works are specifically notable as they come from a time and place that is regarded as the birthplace of advanced civilizations in Antiquity.

Although many of these works no longer exist in their entirety, they often depict just enough to give us a deeper insight into the lives of the Sumerian people.

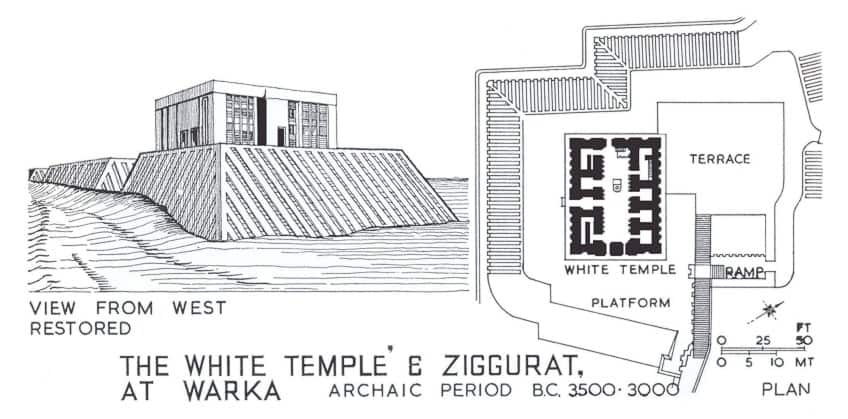

The White Temple and Great Ziggurat of Uruk (c. 4000 BCE)

| Artist | Unknown (c. 4000 BCE) |

| Date Completed | c. 4000 BCE |

| Medium | Stone Brick |

| Current Location | Iraq |

Uruk was an important city in early Sumerian civilization and the birthplace of the legendary Sumerian hero Gilgamesh, who appears in the legendary epic poem of the same name, one of the first instances of storytelling that has survived to the present day. The ruins of one of Sumer’s most prominent temples now sizzle in the Iraqi heat. To imagine the ziggurat as it was 5,000 years ago, visitors, archaeologists, and historians must use their imaginations.

Age, sun, wind, and erosion have all taken their toll on the edifice, but we may piece together an image of what it appeared like at the peak of Sumer’s dominance from literature and archeological interpretation.

The Sumerians, like many other civilizations, believed that the gods dwelt in the sky, therefore they built many of their shrines on the highest elevation feasible and as tall as construction technology permitted at the time. A ziggurat is a pyramid with steps. It is a wide one in this case, with a big, flat region at its peak where a great temple was built. Priests would give sacrifices and offerings to the gods and hear instructions from the gods.

Historians believe that the temple took 1,500 workmen five years to build.

Archeologists discovered the scorched skeleton remains of a lion and a leopard within the temple, as well as a variety of stone tablets showing the temple’s inventory and a fire pit where it is thought that burnt gifts were made to their deities. They also believe they have discovered traces of a spring or water system within the temple, indicating a degree of technical expertise that is beyond what we would ordinarily connect with extremely ancient periods.

The Stele of the Vultures (c. 2800 BCE)

| Artist | Unknown (c. 2800 BCE) |

| Date Completed | c. 2800 BCE |

| Medium | Limestone |

| Current Location | Musée du Louvre, Paris |

Archeologists unearthed pieces of a stone tablet etched in low relief that had been created as a battle memorial for King Eannatum from the archaeological site of Lagash, a Sumerian city-state. On one side of the monument, images and inscriptions describe the military victories of the all-conquering King Eannatum. He is shown as a giant, leading his troops into war.

Nearby are mounds of their opponents’ lifeless bodies, as vultures hover overhead carrying severed bits of the slain. The consent of the Gods is shown on the opposite side of the stone.

It shows a deity carrying the Lagash heraldic sign while efficiently slaughtering its adversaries. This masterpiece of storytelling relief sculpture is said to be the first known example of a tale told in images, of continuous visual art, with the topic “war” – one of four major subjects of the day, the others were gods, kings, and hunting.

It is a significant piece of art from the late Sumerian era, although it is less indicative of Sumer art in general than the small animal figures, seals, and shell plaques – all of which were common products of the early state’s workshops.

The Standard of Ur (c. 2600 BCE)

| Artist | Unknown (c. 2600 BCE) |

| Date Completed | c. 2600 BCE |

| Medium | Limestone, shell, bitumen, lapis lazuli |

| Current Location | British Museum, London |

The Standard of Ur, discovered by British archeologists in the 1920s, is a stunning work of art that dates back 4,600 years. The artwork is a mosaic, not a piece of fabric, as the name implies. Though most of the artwork has been lost to history and criminals, a large part of it is now housed in London’s British Museum. The mosaic is constructed of red limestone with a blue backdrop of lapis lazuli. These items were not inexpensive, and the mosaic was created for the tomb of Ur-Pabilsag, a ruler who died in approximately 2550 BC.

The mosaic tells a portion of his history and rule and provides a glimpse into the Mesopotamian culture.

The mosaic is fairly small yet contains a wealth of information about ancient Mesopotamia. The two bits that have survived have been designated “War” and “Peace.” The first depicts the monarch, a towering figure, looking out his chariot at a parade of nude prisoners. Mesopotamian warriors are seen wearing helmets and holding weapons. A handful of horse-drawn chariots are also visible. We can tell what these soldiers were wearing and how they battled from these pictures.

Bits are missing from the horses’ mouths since they were only invented a thousand years later. They were instead guided by other means, such as ropes running along or within the nose.

Opponents are displayed in front of them and crushed beneath the chariots. “Peace,” the other fragment, depicts an oversized king at the head of a feast that incorporates a lyre player, a singer, fish, and other animals, as well as various vegetables and fruits.

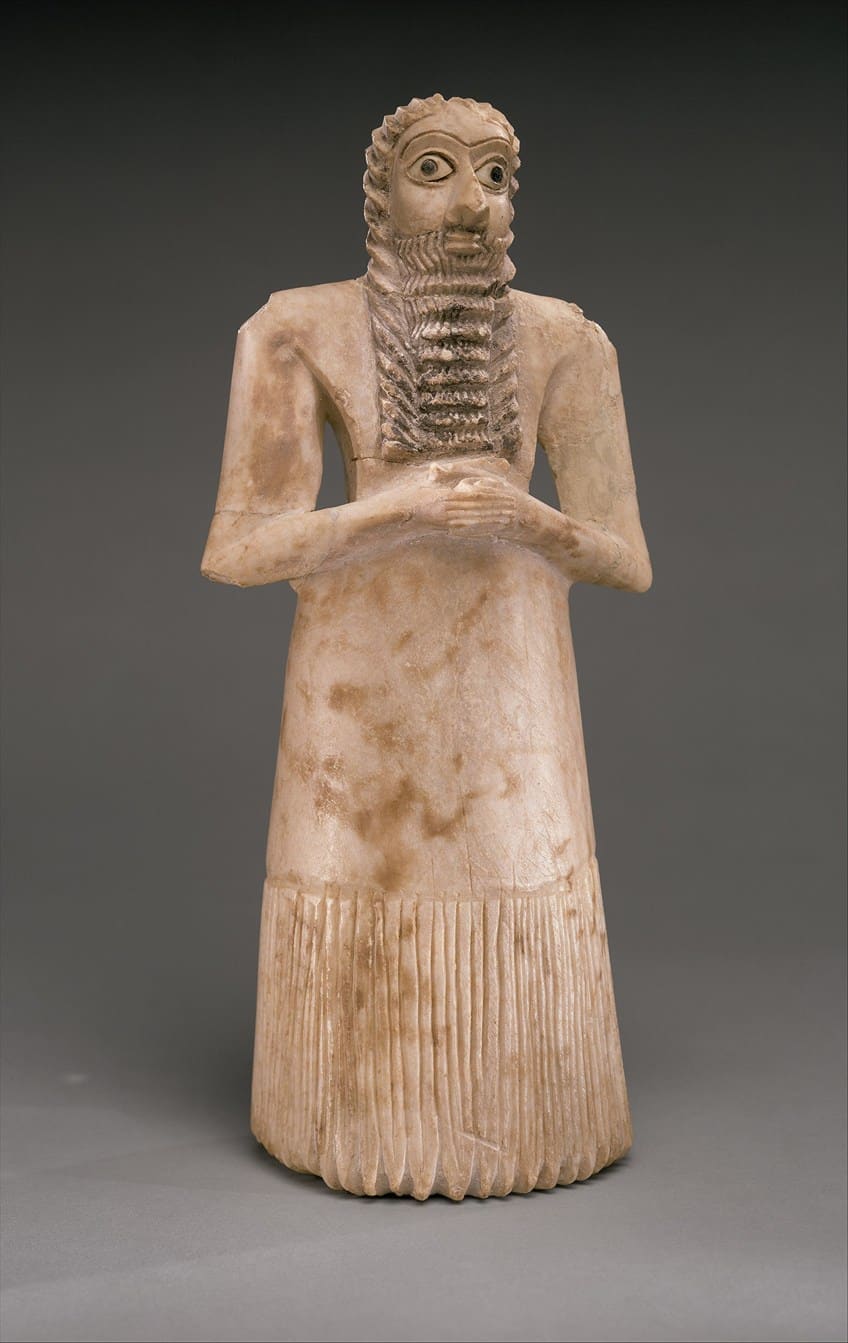

Tell Asmar Hoard (2550 BCE)

| Artist | Unknown (c. 2550 BCE) |

| Date Completed | c. 2550 BCE |

| Medium | Limestone, gypsum |

| Current Location | Iraq Museum, Baghdad |

These sculptures represented the departed in the same way as worshipers now light candles and offer a prayer to commemorate their loved ones in various Christian churches. Many times, names and handwritten prayers have been discovered at the base of the figures. Tell Asmar’s 12 figurines were discovered together in a temple location.

The statuettes’ wide, alien-like eyes were thought to ensure that they could perceive any messages or reactions supplied by the gods, no matter how little or obscure.

In total, eight of the figures are made of gypsum, two of which are constructed of limestone, and one is made of alabaster. The dark, enormous eyes are made of coal, while the pupils of one figure are made of lapis lazuli. The men’s beards, as well as various dark lines and gradations on the statues, were also inlaid with bituminous coal.

The Victory Stele of Naram-Sin (c. 2500 BCE)

| Artist | Unknown (c. 2500 BCE) |

| Date Completed | c. 2500 BCE |

| Medium | Limestone |

| Current Location | Louvre Museum, Paris |

Another one of the historic Mesopotamian civilization was Akkadia, which reigned over most of Mesopotamia around 2500 BCE. The Akkadians possessed the majority of the accessible lengths of the Euphrates and Tigris rivers, giving them tremendous influence. The Akkadians, like other nations throughout the millennia, created monuments in commemoration of their famous rulers and heroes, elevating them to God-like prominence in the process.

The Naram-Sin Victory Stele celebrates the conquest of the Akkadian king Naram-Sin against the Lullubi who resided in the Zagros Mountains.

Just by glancing at this stele, we can learn a lot about King Naram-Sin. The majority of Mesopotamian and subsequent military friezes are horizontal, with the monarch walking or riding at the front or back of a procession of troops, captives, or priests.

In this example, the stele represents Naram-Sin’s triumph in an upward, semi-triangular way, with the king at the peak and considerably bigger than the characters below him, which diminish in size as you approach the stone’s bottom.

The Akkadians thought that only departed kings could become gods, yet here Naram-Sin is sporting a god’s headpiece and his face is shown to be that of a lion, which most other works tell us is solely reserved for divine beings. Naram-Sin, like many rulers who came after him, clearly had an ego.

Lamassu (c. 883 BCE)

| Artist | Unknown (c. 883 BCE) |

| Date Completed | c. 883 BCE |

| Medium | Gypsum alabaster |

| Current Location | The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City |

The Lamassu were guardian deities in Mesopotamian culture, with regal human heads, lion or bull bodies, and bird wings. The lamassu, like China’s guardian lion canines and dragons, protected shrines and palaces to keep the monarch and priests safe and ensure that prayers were safeguarded. Most individuals relate the lamassus’ faces with the features of Mesopotamian monarchs or clergy. They wear a huge miter-style hat with a flat top (similar to Eastern Orthodox officials’ headgear) and a long beard twisted into curls.

People typically identify the appearance of the lamassu with Mesopotamian monarchs in the same way that we think of the Sphinx as representative of ancient Egypt.

The majority of the remaining lamassu statues are huge and intimidating, as they were meant to be sanctuary guardians and doorways to the deities. The most renowned pair of lamassu stands significantly taller and broader than the humans in Sargon II’s temple at Khorsabad, northern Iraq.

Another intriguing feature of these bull- or lion-like protectors is that they frequently have five legs.

Ashurbanipal and His Queen in the Garden (c. 668 BCE)

| Artist | Unknown (c. 668 BCE) |

| Date Completed | c. 668 BCE |

| Medium | Gypsum alabaster |

| Current Location | British Museum, London |

Ashurbanipal ruled the Assyrian Empire around 660 BCE making him a relatively recent monarch in comparison to those previously named. Therefore, in terms of chronology, Ashurbanipal’s rule is closer to us today than it was to the inhabitants of Ur 3,200 years ago. In this sculpture of the king and his queen, we observe life in the king’s palace in a different context.

The couple is resting and having fun here. This demonstrates that the queen was either highly valued or that the monarch adored her – or both.

In contrast to the more recognized Egyptian art, queens did not figure frequently in Assyrian art. In terms of Egypt, we can see weaponry in the backdrop of the frieze, implying a recent operation against the Egyptians. In the backdrop, we notice wine goblets, slaves, fruit, and a decapitated skull. Incense burners and slaves may also be seen brushing away desert flies. Some historians have remarked that the faces of the queen and king in this artwork have been disfigured, while the features of the slaves have not. As a result, historians think Ashurbanipal and his queen were despised individuals.

After the Babylonians invaded Mesopotamia in the early second century BCE, the Sumerians progressively lost their identity and culture and stopped functioning as a political power. All understanding of their culture, languages, and technologies, was finally lost. Their mysteries remained buried in the Iraqi deserts until the 19th century when British and French archaeologists discovered Sumerian relics while looking for proof of the ancient Assyrians. Thanks to their efforts we now have many fine examples of Sumer art to enjoy, such as the Sumerian statues and Sumerian carvings that we have explored today.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Sumerian Art?

Sumerian art was created by the people of Southern Mesopotamia, known as Sumer. It is noted as being the birthplace of the first civilizations that had a language, artforms, architecture, and infrastructure. They were so advanced for their time that Egyptian artworks from the same period pale in comparison when it comes to quality and craftsmanship. Due to the incredible details of Sumerian carvings and tablets, we can piece together the history of Sumerian culture and art and learn about the innovations that helped shift the face of the ancient world. Sumerian art was mainly focused on the religious and mythological characters of Mesopotamia.

Why Are There No Sumer Paintings?

Most of the Sumer art that we have left today is what was made from clay, brick, or limestone. Therefore, we don’t have examples of Sumer paintings left. There are incredible mosaics as well, and Sumerian statues that portray the various gods of the Sumerian faith. After the collapse of the Sumerian Empire following the rise of the Babylonians, everything that was related to the culture was destroyed or buried beneath the sands of the desert over time. However, today we can view these amazing artifacts in museums around the world thanks to the 19th-century archeologists from France and England that excavated these ancient sites.

Why Is Sumer Art Important?

Many historians consider it to be one of the first real civilizations. This is because it had a written language and many advances that were new in that period. They created the potter’s wheel, and their military capabilities were highly advanced. Their settlements were well planned and their art displayed a mastery of sculpture as well. They were also known for being extremely good leather workers and metalworkers.

Jordan Anthony is a Cape Town-based film photographer, curator, and arts writer. She holds a Bachelor of Art in Fine Arts from the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, where she explored themes like healing, identity, dreams, and intuitive creation in her Contemporary art practice. Jordan has collaborated with various local art institutions, including the KZNSA Gallery in Durban, the Turbine Art Fair, and the Wits Art Museum. Her photography focuses on abstract color manipulations, portraiture, candid shots, and urban landscapes. She’s intrigued by philosophy, memory, and esotericism, drawing inspiration from Surrealism, Fluxus, and ancient civilizations, as well as childhood influences and found objects. Jordan is working for artfilemagazine since 2022 and writes blog posts about art history and photography.

Learn more about Jordan Anthony and about us.

Cite this Article

Jordan, Anthony, “Sumerian Art – Explore the Important History of Sumer Art.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. September 26, 2022. URL: https://artfilemagazine.com/sumerian-art/

Anthony, J. (2022, 26 September). Sumerian Art – Explore the Important History of Sumer Art. artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. https://artfilemagazine.com/sumerian-art/

Anthony, Jordan. “Sumerian Art – Explore the Important History of Sumer Art.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source, September 26, 2022. https://artfilemagazine.com/sumerian-art/.