“The Kiss” Sculpture by Auguste Rodin – Dante’s Doomed Lovers

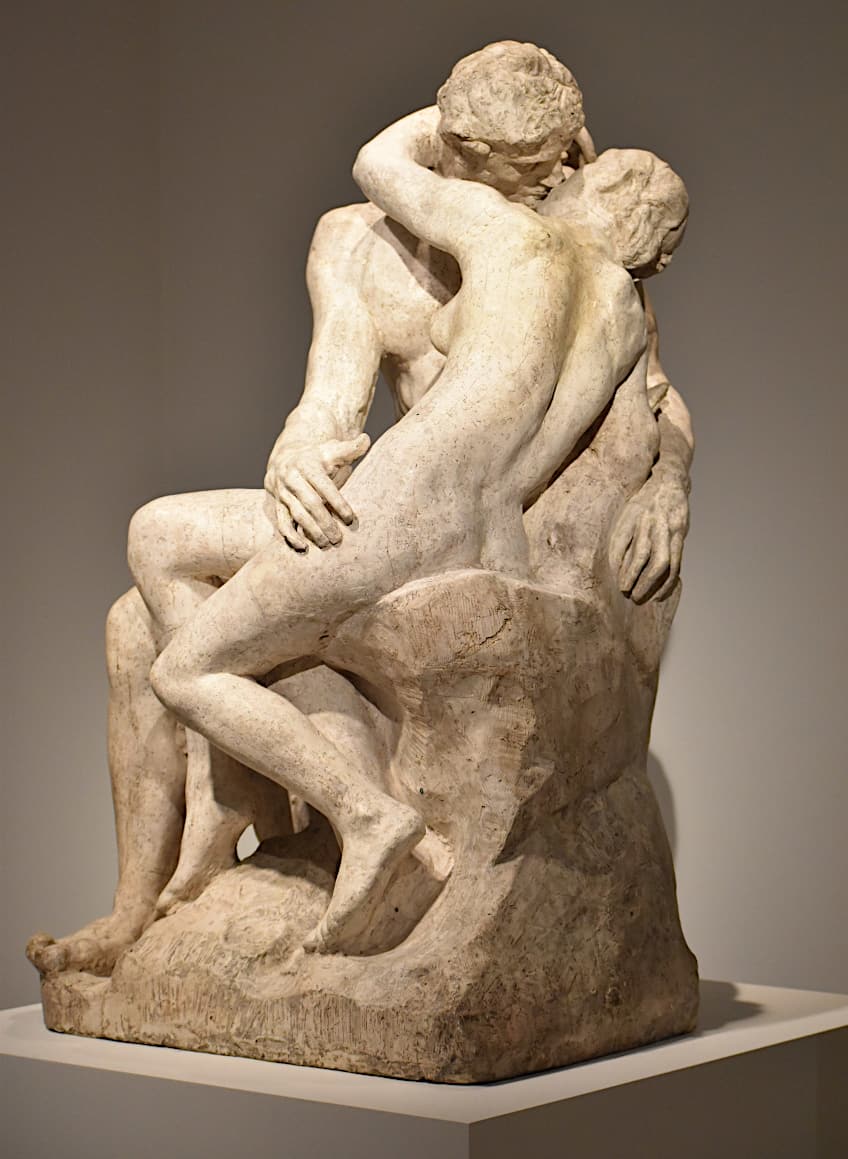

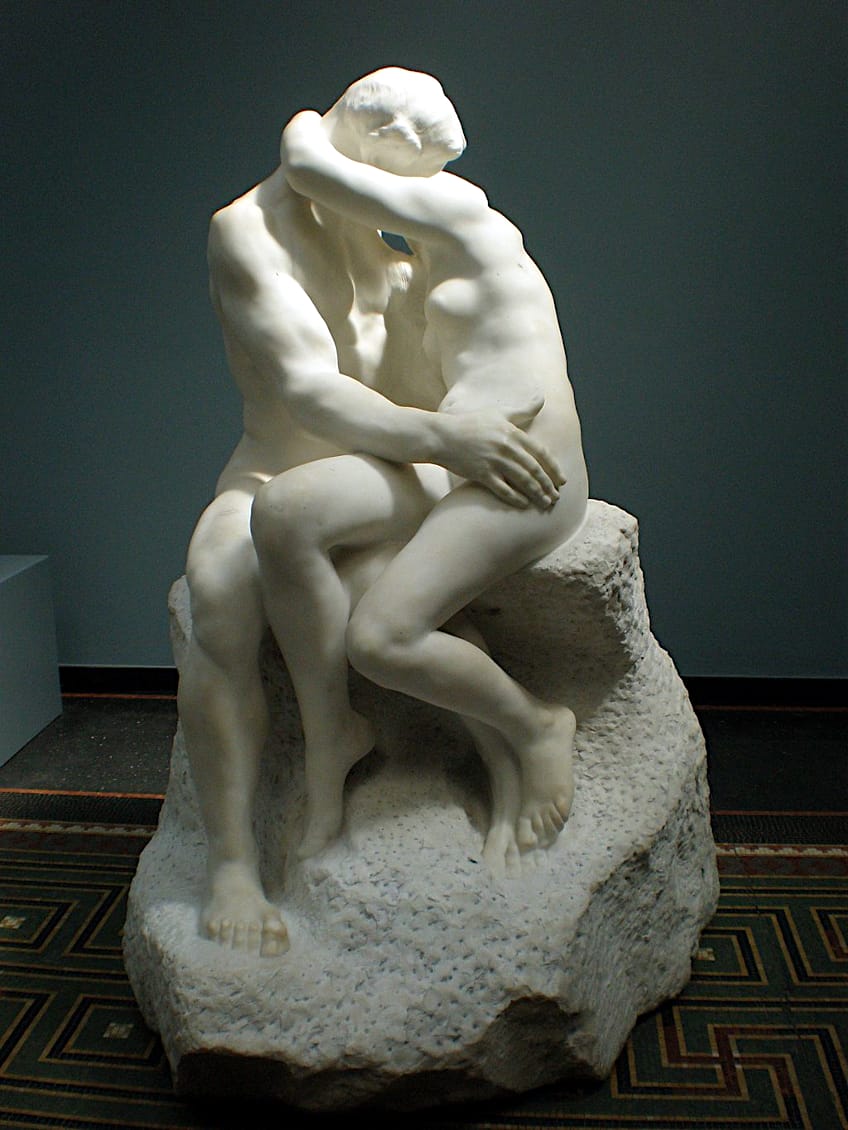

The Kiss statue is among the most renowned of Auguste Rodin’s sculptures. The Kiss sculpture by Auguste Rodin depicts an embracing naked couple and was originally part of a collection of sculptures and reliefs embellishing Rodin’s enormous bronze entryway, The Gates of Hell (1917), designed for a proposed museum of art in Paris. The couple was subsequently removed from the door design and replaced by another pair on the column to the right. Who was The Kiss sculptor and what is the history of this famous sculpture? To find out, let’s learn more about The Kiss sculpture by Auguste Rodin.

Contents

The Kiss Sculpture by Auguste Rodin

| Sculptor | François Auguste René Rodin (1840 – 1917) |

| Date Completed | 1882 |

| Medium | Marble |

| Dimensions (m) | 1,82 x 1,12 x 1,17 |

| Current Location | Musée Rodin, Paris, France |

There were three full-scale iterations of The Kiss statue produced throughout Rodin’s lifetime. It ranks among the greatest representations of sexual love because of its combination of sensuality and romanticism. Nevertheless, Rodin thought it was too conventional, referring to it as a big carved knick-knack using the customary format.

So, who was The Kiss sculptor, and what led to the creation of The Kiss statue, one of the most famous Auguste Rodin sculptures ever produced?

An Introduction to The Kiss Sculptor

| Full Name | François Auguste René Rodin |

| Nationality | French |

| Date of Birth | 12 November 1840 |

| Date of Death | 17 November 1917 |

| Place of Birth | Paris, France |

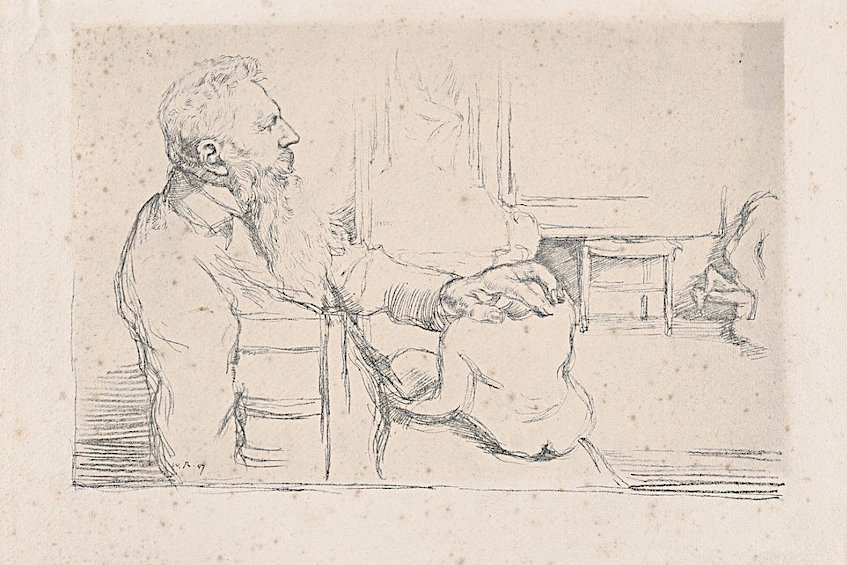

Auguste Rodin was greatly influenced by tradition while rejecting its idealized forms. Over the duration of a career that encompassed the late 1800s and early 1900s, he established creative approaches that prepared the way for contemporary sculpting. He thought that art should be truthful to nature, which influenced his approach to models and materials.

Some of his works sparked controversy, such as the controversy surrounding The Age of Bronze (1875), as well as his incomplete works, most notably The Gates of Hell (1917).

His brilliance was in expressing deep truths about the human mind and condition, and his sight went behind the world’s surface. Rodin created an agile approach for expressing severe bodily states that match expressions of inner conflict or overpowering delight while exploring this region under the surface of everyday life.

He created a world of enormous emotion and sorrow, a realm of imagination that transcended the humdrum occurrences of daily life. Rodin did not attend the famed École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. But his attention to the human physical figure and use of varied materials such as marble, bronze, plaster, and clay indicate his respect for sculptural history and his willingness to work inside the system for contracts and chances for exhibition.

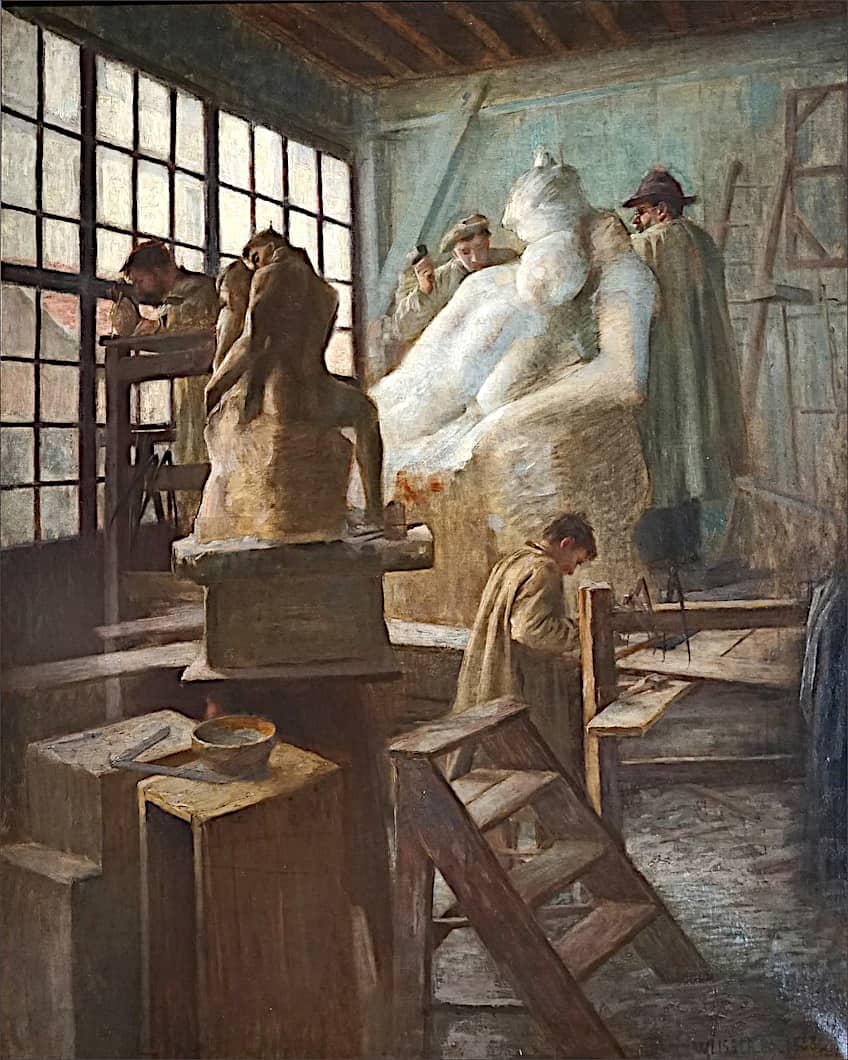

Auguste Rodin’s signature features, such as his refusal to smooth over or conceal indications of his sculpting technique and the fabrication of sculptures from human features such as hands, were groundbreaking at the time. Numerous artists who followed him, including those who collaborated in his workshop, such as Constantin Brancusi and Aristide Maillol, expanded on the evocative complexity of his creations.

The Kiss statue originates from another of Auguste Rodin’s sculptures, The Gates of Hell. The Gates of Hell is Auguste Rodin’s signature work and is crucial to understanding his aesthetic goals. He worked on The Gates for 37 years, adding, removing, and changing the more than 200 figures that comprise the doors and their frame on a daily basis.

He had a fresh plaster of The Gates built near the end of his life, while he was planning the establishment of a museum dedicated to his works because the existing model was breaking apart after so much revising. Because of the sculptor’s poor health and the onset of World War I, his ambitions to carve the piece in marble never materialized, and The Gates only existed in plaster at the time.

Understanding The Kiss Statue

Although it is widely recognized as one of the most prominent depictions of sexual attraction in history, Auguste Rodin’s statue of two lovers has a complicated – and contentious – background. Auguste Rodin’s massive marble statue of two nude lovers joined in ecstasy, referred to simply as The Kiss, must be among the most candid – and most iconic – depictions of sexual love in the art world’s history.

With their smooth and flexible bodies, which create a dramatic contrast to the harshly textured rock on which they rest, Rodin’s pair of lovers look ageless and idealistic: a universal expression of sexual passion, ignorant to everything else around them.

During Auguste Rodin’s lifetime, three larger-than-life-size marble replicas of the artwork were created. The oldest is in the possession of the Musée Rodin in Paris, which reopened after undergoing significant renovations at its residence, the Hôtel Biron, a beautiful 18th Century house that the artist occupied as his Paris workshop until his passing in 1917.

The museum has always been one of the most charming places in town. It remains so now that it has been freshened up with renovated woodwork and parquet flooring; indeed, its charm has been improved. And, fittingly for this paradise for young couples, The Kiss is prominently located in the midst of a gallery on the ground level, instantly visible as you approach the building.

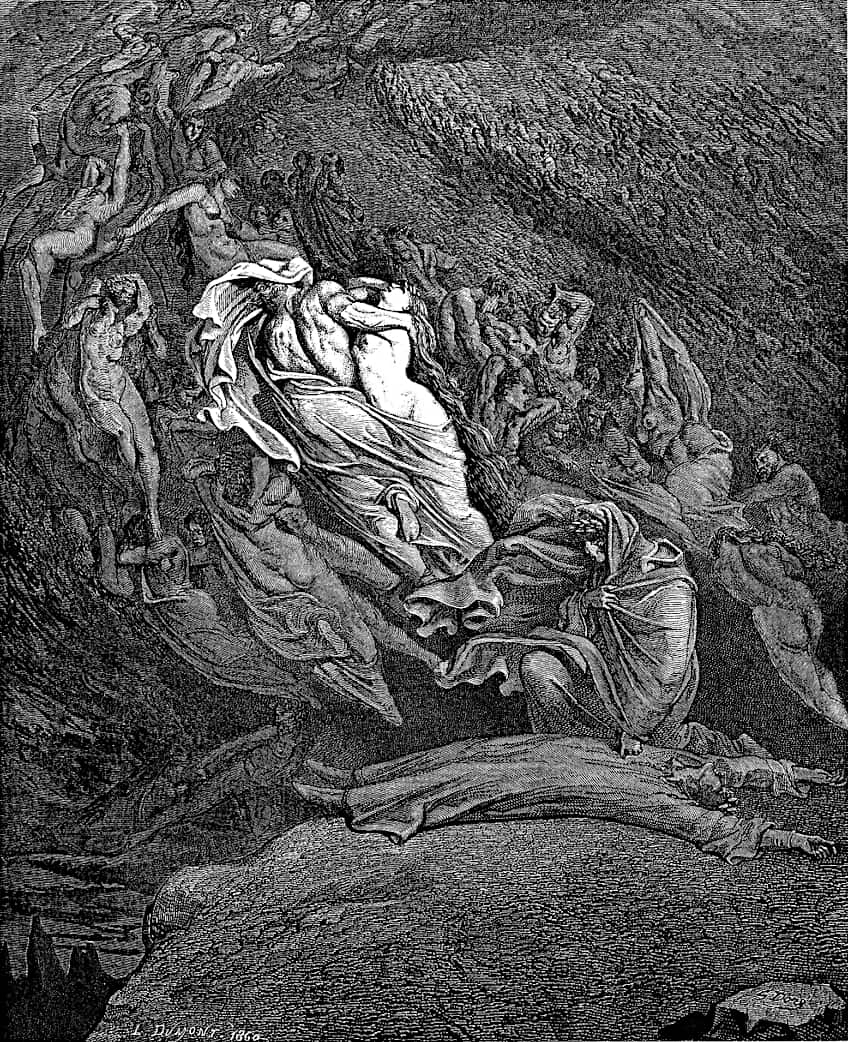

A Doomed Love

While The Kiss appears to be buoyantly joyful, uncomplicated, and carefree, the narrative of its origin and aftermath is more complicated. Did you realize for example, that Rodin’s paramours symbolize a couple of condemned adulterers from Dante’s Inferno (1314)? The sculpture’s roots may be traced back to 1880, when Rodin, the child of a police clerk and raised in a working-class suburb of Paris, was nearing 40 by which time he already made a name for himself. The French state commissioned him for the first time that year to create a pair of massive bronze doors for a new museum of decorative arts.

Rodin chose Dante’s Inferno as his motif, and he intended to sculpt a couple in relief in the center of the left-hand door panel from the start. The group, dubbed Faith, would depict the illicit love of Francesca and Paolo, whom Dante encountered in the second circle of hell, beset by an everlasting whirlwind, and who were a frequent topic in 19th-century artworks.

Based on the original 13th Century account, Paolo and Francesca met while studying accounts of courtly love. Once Francesca’s husband, who also happened to be Paolo’s brother, discovered their affair, he murdered them. Rodin chose to show the couple at their first kiss. Close inspection reveals the novel sliding from Paolo’s left hand.

Diversion from the Gates of Hell

The ideas for the new museum, however, fell through in the middle of the 1880s, and the Gates of Hell were not produced in bronze until after his passing. By 1886, however, Rodin had already come to the conclusion that his bas-relief of the lovers would look better as a sizable, spiraling sculpture in the round. The French government subsequently hired Rodin the next year to complete the piece in marble on a size that was larger than life.

The Kiss remained incomplete in plaster in Rodin’s workshop for the next decade while he turned his attention elsewhere.

In 1898, nevertheless, Rodin opted to display it at the annual Salon, with his monolithic monument of the novelist Honoré de Balzac, which the cultural historian and Rodin specialist Catherine Lampert characterized as the creator’s “most radical piece”. While the second sculpture, in which the author stands covered in a robe hiding a weirdly libidinous bulge, was derided by the public, The Kiss was an instant success. It was immediately replicated in bronze in various sizes, and more than 300 castings had surfaced by 1917. “It’s a beacon for romantic, sensual, young emotion”, said one historian.

Creation of Another Copy

In 1900, the homosexual Bostonian connoisseur and antiquarian Edward Perry Warren, wondered whether The Kiss sculptor would consider constructing a full-size reproduction of the sculpture “in the best conceivable marble” for his own personal collection. The French artist consented and an agreement was written out, stating Rodin’s remuneration of 20,000 francs, in addition to the provision that “the sexual organ of the male must be finished”. The final sculpture was brought in the summer of 1904, but it was too huge for Warren’s residence and had to be ungraciously housed in the stable block.

Edward Perry Warren donated it to Lewes Town Hall during the First World War. It was set up in the Assembly Room, which served as an entertainment area for troops stationed in the town. The venue hosted regular boxing contests.

The immorality of its naked characters was considered repulsive by the town’s inhabitants. They feared that it might promote obscene behavior among the troops. As result, it was enclosed by a rail and draped with a sheet.

Approximately two years later, it was delivered back to Warren and concealed by hay bales, to safeguard it from shelling. It was eventually acquired by the Tate in 1953, many years after Edward Perry Warren’s passing in 1928.

Modern Artistic Appropriation of The Kiss Statue

Around 50 years later, the sculpture was stirring controversy in Britain once more. It had formerly filled the main rotunda of what is now Tate Britain, but with the inauguration of Tate Modern in 2000, it was relocated to the newer gallery, where it sat on a platform near the restrooms. Cornelia Parker, a British artist, opted to return the sculpture to its prime place in Tate Britain after she was asked to take part in the Tate Triennial in 2003.

This was an allusion to a notorious wartime Surrealism exhibit in New York planned by the contemporary artist Marcel Duchamp, who traversed the art gallery with a “mile of thread” in order for his tangled web to hide the other works. “It felt like a war between two aesthetics”, Parker says of her intervention.

“I’ve always adored Rodin, but I certainly appreciate Duchamp more. And I thought that, while being the most renowned sculpture at the Tate — people like it – it had gotten a little cliched. I wanted to give it back the intricacy it used to have: that unions can be painful, and not simply this romantic vision. So the thread represented the complexities of relationships”. Not everybody was impressed with Parker’s proposal.

Negative publicity swiftly followed: “Some of it was extremely unpleasant, but it didn’t shock me,” the artist says. “Perhaps that appeared to me to be an incredibly insulting thing for me to do”. Before the security could interfere, one enraged Tate visitor took out a pair of scissors and cut Parker’s string. The Tate wanted to press charges, but she didn’t want to add fuel to the assailant’s fire.

“Instead I simply knotted the thread back together and put it back on”, she explains, “and that made it even less poetic and somewhat more punk. I assumed Duchamp would have appreciated it, so I figured I should as well give it a decent go”. Obviously, Duchamp’s brand of conceptual art developed in the early half of the last century could not have been any more unlike Rodin’s materialist and formal concerns. Rodin, on the other hand, was a brilliant inventor. His creativity was sparked by his closeness to the women and men who posed for him and his modeling in the clay of their bodies rotated 360 degrees, is still breath-taking and unrivaled.

Rodin and Sexuality

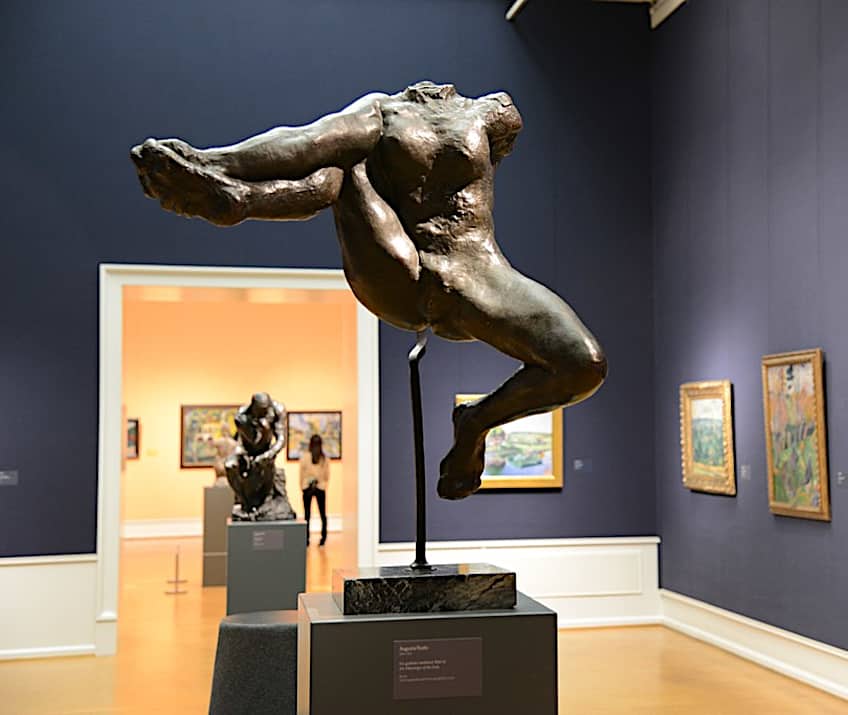

This is somewhat demonstrated in Auguste Rodin’s The Kiss, as the woman actively fulfills the man’s sexual urge. (The sculptor Camille Claudel, who was rumored to have been Rodin’s mistress and the model for the woman in the sculpture, wasn’t really involved in the creation of the piece). The stunning Iris, Messenger of the Gods (ca. 1895), in which a headless nude hurtles through the cosmos in mid-air, is one such piece of artwork that makes Rodin’s interest in feminine sexuality even more clear. Her right-hand grips her foot in a motion that may refer to the titillating can-can dancer routines, causing her legs to spread apart and exposing her genitalia.

Auguste Rodin’s The Kiss could not be regarded as that provocative in comparison. It is more like a polished, sophisticated version of desire—a kiss rather than an orgasm. This may be the reason why Rodin himself disregarded The Kiss, describing it as “a big carved knick-knack following the conventional trend” at one point.

But, like Parker’s mile of thread, understanding the sculpture’s past complicates our reactions to it in a way that, in many people’s opinion, is both helpful and exciting. Despite popular belief to the contrary, the path of genuine love seldom does go smoothly, so perhaps the story is accurate.

The Kiss Statue in Popular Culture

The statue is supposed to have been the idea for the song Turn Of The Century, by Yes, the band from Britain. It was included in the 1977 release. Archie Bunker attempts to get his daughter Gloria to return a copy of the sculpture she received from the Bunkers’ friend Irene Lorenzo in the All in the Family episode which was aptly titled Archie and The Kiss, which features the statue in its narrative. Archie shows his displeasure at the sexuality and morals of the artwork.

In Monty Python’s Flying Circus, a Terry Gilliam animation features the statue. The female stretches her left leg straight out, while the man slides his right hand over it, plugging openings with his fingers and playing her like an accordion.

Subsequently, the same sculpture was briefly seen in the Gilliam-directed film 12 Monkeys (1995). The Harvey’s Brewery in Lewes, Sussex, has created a beer called “Kiss” that is sold in bottles and on draft on the 14th of February and has an image of the statue on its label.

The Kiss sculpture by Auguste Rodin is a universal symbol. Like the gods and heroes of ancient sculpture, it depicts a timeless human act while being naked and, in certain cases, made of marble. It is also really contemporary considering the period it was produced in. For Rodin, a plinth would not work for this piece. These are people living in our reality, not entities to be exalted on a pedestal. Furthermore, the woman is an equal participant in desire, which is innovative for the 19th century. This pair was created by Rodin for the Gates of Hell, a bronze entryway that depicts passages from the epic poem. They were modeled on an adulterous couple that is represented in Dante’s Inferno. They weren’t tormented enough, though, to make the cut.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who Was The Kiss Sculptor?

The Kiss is probably one of the most well-known Auguste Rodin sculptures. Auguste Rodin was the only child of Marie Cheffer and Jean-Baptiste Rodin, both of whom were first-generation Parisians of low means. Nothing at all in his family history or environment pointed to him being an artist. However, at the age of 13, Rodin opted to enroll at the Ecole Spèciale de Dessin et de Mathématique, an institute dedicated to educating the French nation’s creators and artists. During his education, young Rodin had higher aspirations for himself, namely to become a sculptor. He attempted three times to get entrance to the Ecole des Beaux-Arts but failed each time. The 1880s, when he was in his 40s, were the most passionate and creative years of his life. It was around this period that he modeled most of his artwork’s figures. It was also around this time that he met Camille Claudel, the lady who became the center of Rodin’s most tragic and overwhelming devotion. He suffered greatly as a result of this experience, but it provided fertile ground for the emergence of a significant number of sexual organizations in the 1880s.

What Was The Kiss About?

Auguste Rodin’s The Kiss is a statue depicting embracing lovers. It was originally designed to represent the 13th-century Italian heiress memorialized in Dante’s Inferno. The woman had developed feelings for her husband’s brother. The pair is found and slain by the husband, after falling in love while studying the tale of Lancelot and Guinevere. The book may be seen in Paulo’s hand in the artwork. The lovers’ lips do not make contact in the statue, implying that they were disturbed and died without their lips ever touching. This artwork was originally intended to be part of a set of reliefs that adorned Rodin’s enormous bronze doorway and depicted scenes from Dante’s book, The Divine Comedy (1314). The couple was eventually excluded from the Gates and substituted by another pair of lovers. Another of Rodin’s most famous works, The Thinker, was created to sit at the very apex of the gates contemplating the scenes of torment below.

What Did People Think of The Kiss Statue?

Rodin’s approach to sculpting the pair was to give honor to them both as complete partners in desire. The sculpture’s sexiness made it contentious, particularly when a bronze version of The Kiss was transported to the World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893. The sculpture was deemed unfit for wide public sight and was restricted to private viewings only. However, the artist himself thought that the piece was rather mild and not particularly well executed, stating that it had been produced in the usual manner typical of the day.

What Is the Link Between The Kiss and Cornelia Parker?

Cornelia Parker, an artist, interfered with The Kiss with the consent of the Tate Britain gallery, where it was on display at the time, by surrounding the artwork in a mile of string in the spring of 2003. This was a nod to Marcel Duchamp’s 1942 usage of the same length of rope to build a web inside an exhibition. Although the interference had been sanctioned by the museum, many spectators of the artwork deemed it insulting to the artwork, provoking a further unapproved action, in which Parker’s rope was severed by Piers Butler, as lovers stood around indulging in live kissing. One has to wonder if the interference of Parker’s work can itself be considered an act of art. Whether it was deemed so by the gallery seems rather immaterial – none of the artists who intervened with the original piece had the artist’s permission in the first place. Art is often reactionary, so, as long as the original artwork was not damaged, then perhaps both acts can be regarded as artistic efforts.

Nicolene Burger, a South African multimedia artist and creative consultant, specializes in oil painting and performance art. She earned her BA in Visual Arts from Stellenbosch University in 2017. Nicolene’s artistic journey includes exhibitions in South Korea, participation in the 2019 ICA Live Art Workshop, and solo exhibitions. She is currently pursuing a practice-based master’s degree in theater and performance. Nicolene focuses on fostering sustainable creative practices and offers coaching sessions for fellow artists, emphasizing the profound communicative power of art for healing and connection. Nicolene writes blog posts on art history for artfilemagazine with a focus on famous artists and contemporary art.

Learn more about Nicolene Burger and about us.

Cite this Article

Nicolene, Burger, ““The Kiss” Sculpture by Auguste Rodin – Dante’s Doomed Lovers.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. March 27, 2023. URL: https://artfilemagazine.com/the-kiss-sculpture-by-auguste-rodin/

Burger, N. (2023, 27 March). “The Kiss” Sculpture by Auguste Rodin – Dante’s Doomed Lovers. artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. https://artfilemagazine.com/the-kiss-sculpture-by-auguste-rodin/

Burger, Nicolene. ““The Kiss” Sculpture by Auguste Rodin – Dante’s Doomed Lovers.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source, March 27, 2023. https://artfilemagazine.com/the-kiss-sculpture-by-auguste-rodin/.