Formalism Art – A Unique Method for Analyzing Art

In the mid to late 19th century, formal art analysis began to gain recognition amidst the rise of Abstract painting. By the early 20th century, with movements like Cubism at the forefront, Formalism art had reached new heights. One of the most well-known catchphrases in art history, “L’art pour l’art” or “Art for art’s sake,” is closely associated with this formalistic theory.

Contents

It Is What It Is in Formalist Art

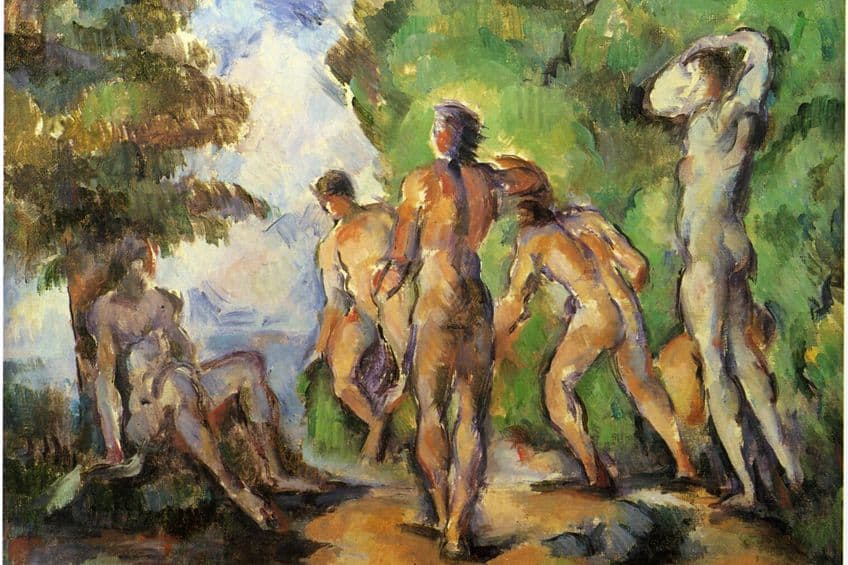

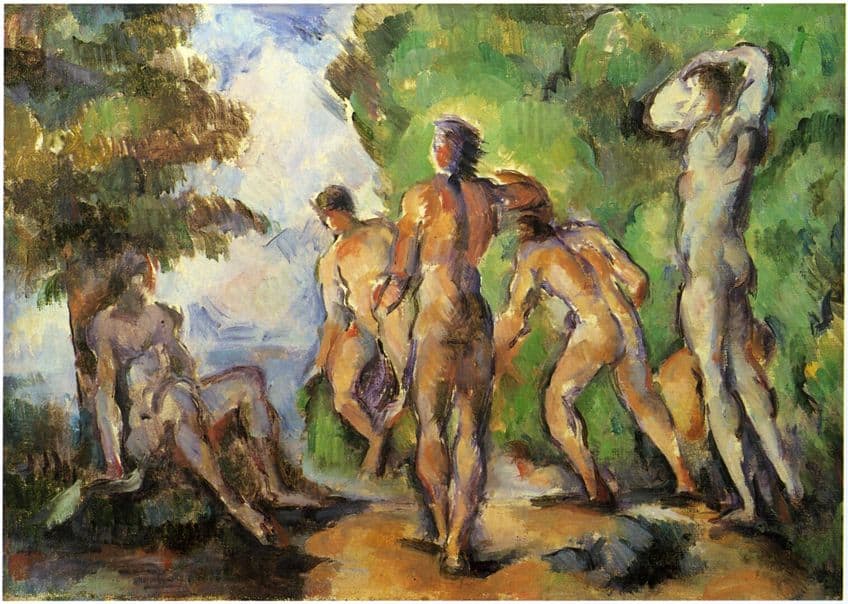

Unlike Cubism or Impressionism, Formalism art is not quite an artistic movement or style. Although it does encompass a practical approach, it is more of a critical method for the interpretation of art. That is why it is so overarching. A wide variety of artists such as Vincent van Gogh, Piet Mondrian, Paul Cézanne, Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, and Lucien Smith have been associated with Formalism.

What Is Formalism?

The Formalism definition refers to a critical position that concentrates on sensory or material qualities. Art theorists and historians often describe Formalism in art as an approach to interpreting art that strictly adheres to structural forms. As Formalism interprets a work of art through an analysis of form and style, it places an artwork’s value in the relationships between basic compositional elements that work together to communicate a visual expression. The key to understanding what Formalism is is in the word form.

The formal elements of the work refer to the spatial organization of elements or the compositional elements.

In Formalism the visual components of the artwork can include line, color, shape, mass, value, symmetry, texture, delineation, and materiality. In the Formalism definition, the only additional significance to the meaning of an artwork is the way the artwork is made in its purely visual aspects. In Formalism art, information deemed irrelevant for the interpretation of an artwork is the artist’s psychology, motivation, intent, technique, subject matter, conceptual, cultural, social, political, or historical context. At most these elements are of secondary importance.

The History of Formal Analysis in Art

The formalistic theory goes all the way back to Plato who was the first philosopher to use the concept of form. Plato’s theories have shaped how we conceive of human perception and formed the basis for the entire discipline of aesthetics. He saw form as an element shared by abstract and tangible phenomena in the natural world. Since the ancient Greeks had long theorized about aesthetics and even invented mathematical proportions to achieve harmony in art, the idea of sets of standards for art was quite established by the time connoisseurship emerged around the 18th century. Connoisseurship was a method of studying artifacts from ancient Rome and Greece. As it relates to the study of European art objects, connoisseurship is a more recent iteration of Formalism.

French philosopher Victor Cousin was the first to use the term ” l’art pour l’art” or “art for art’s sake” during the early 1800s. By the mid-1800s, numerous literary and visual practitioners had adopted the idea that art need not serve any representational, moral, social, spiritual, or emotional purpose. Rejecting any non-aesthetic goals assigned to art, they decided formal beauty was the only quality they wanted to strive for. At the end of the 19th century, connoisseurs could be hired as experts in identifying and authenticating works of art. Bernard Berenson (1865 – 1959) was arguably the most well-known connoisseur of the 20th century. Unlike art historians who had to write, argue, and critique, connoisseurs simply applied their expertise to determine the authenticity of an artwork. Formal analysis techniques were first explored by mid-19th-century art historians like Roger de Piles (1635 – 1709) through his book The Principles of Painting (1743) and various members of the Vienna School of Art History.

A leading advocate of autonomous art history in Vienna, Moritz Thorzing, promoted a division between aesthetics and art history. Franz Wikoff and Alloys Regal who were students of Thorzing’s, developed comparative stylistic analysis methods which avoided any judgment based on personal taste. Prioritizing the purely formal qualities of artwork, the formalistic theory rejected arguments about content and speculation.

Furthering Thorzing’s approach, they contributed to the revaluation of the art of late antiquity, which had previously been perceived as a period of decline.

Emerging in Germany during the late 19th century, Style Analysis is the identification of styles like the Renaissance, Baroque, Neoclassical, Impressionism, etc. The field involves studying how one evolved into the next. In the 20th century, the quintessential style analyst was Heinrich Wolfflin (1864 – 1945) whose book Principles of Art History (1915) analyzed style according to Five Formal Properties: linear, planar, closed, multiplicity, and Absolute clarity – each with its corresponding opposite. In his interpretation of art, Wolfflin makes no mention of the artistic intent, cultural, political, or social context of the work. Principles of Art History (1915) which encourages a strict observation of style only, is still taught to art history students today.

With medical and scientific advances, there were significant population booms and subsequent growth among the working and middle classes. People began traveling more than ever before, resulting in urbanization as people moved from agricultural communities to large cities for work. In this period of rapid industrialization, technological advancements like the invention of the camera changed the way images were interpreted, which would eventually lead to Formalism. Photography challenged the purpose of mediums such as painting creating a necessity for a move towards Formalism. Photography produced a visual accuracy that disrupted the idea that painting was meant to present an illusion of reality.

Formalism in art came from a mixture of connoisseurship, L’art pour l’art, and style analysis. As its history illustrates, Formalistic theory is not simply a movement, but an integral aspect of art appreciation and criticism. Developed by art critics, rather than artists, Formalism is a philosophical doctrine that helps viewers perceive and comprehend form and style.

Immanuel Kant (1724 – 1804)

| Date of Birth | 22 April 1724 |

| Date of Death | 12 February 1804 |

| Place of Birth | Königsberg, Kingdom of Prussia (present-day Russia) |

| Nationality | German |

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, Western thought was dominated by Idealism and later Romanticism. German philosopher Immanuel Kant was famous for his pioneering contributions to the modern question of aesthetic Formalism art. With his broad and systematic philosophical views, Immanuel Kant not only changed society’s understanding of aesthetic theories but the modern philosophical project in general. Immanuel Kant was able to achieve this status because of his quest for universal philosophical truths. In aesthetics, Kant deduced that it was the only form that could be analyzed equally by various viewers. This is how Formalism emerged – as a new form of visual thinking.

In his book Critique of Judgment () Kant reveals himself as a pure Formalist for emphasizing form as the central aspect of beauty.

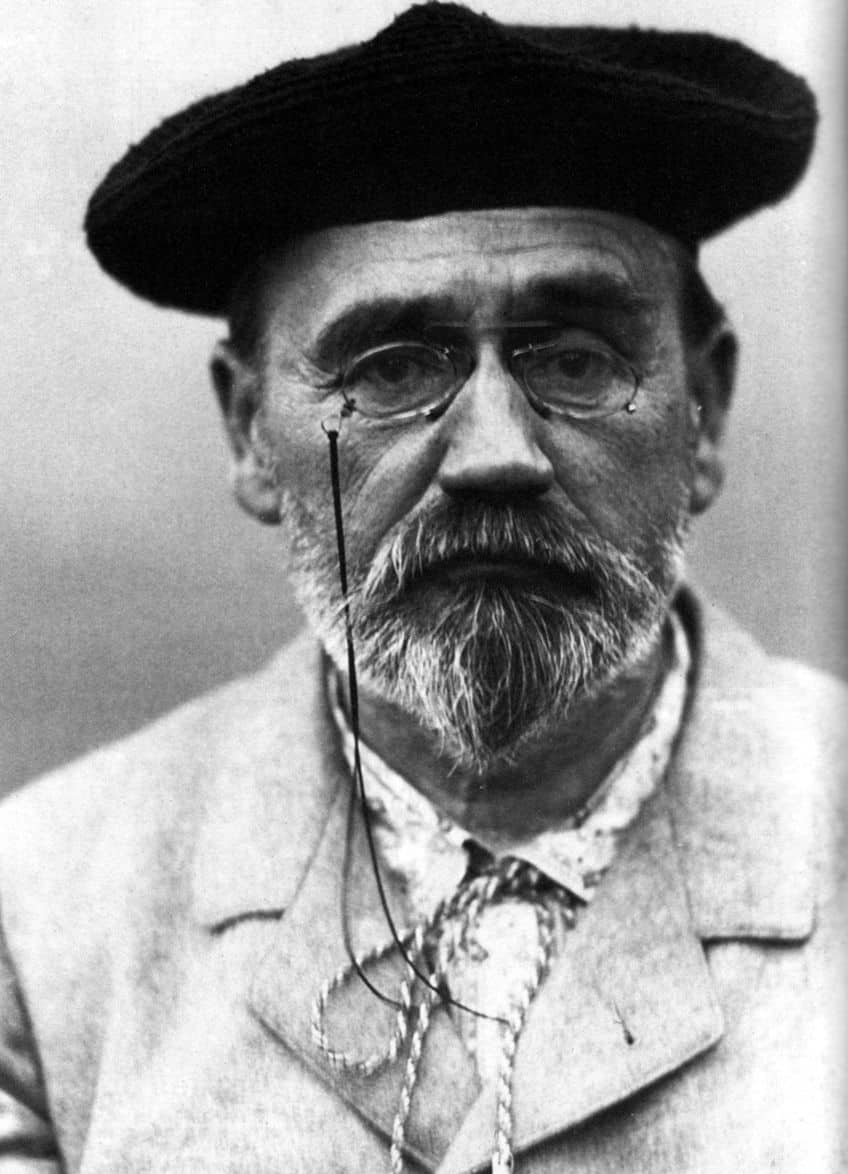

Emile Zola (1840 – 1902)

| Date of Birth | 2 April 1840 |

| Date of Death | 29 September 1902 |

| Place of Birth | Paris, France |

| Nationality | French |

19th-century French writer and critic Emile Zola was an early Formalist who championed the art of Edouard Manet. In New Manner of Painting (), Zola uses Formalistic theory as a modern approach for this new kind of artwork. Unlike critics of the past, who based their interpretations on codes and conventions, Zola sought to analyze artworks based on the simple facts that are its visual elements. Zola stated that the analysis of art should be based on observation, resulting in an empirical experience. An artwork’s observable, external facts, were indicative of the expression and individual style of each of these artists who were not attempting to merely replicate reality.

A work of art was about a visual expression of their own perception and the individual perception of each viewer. Therefore, the meaning of artwork became relative.

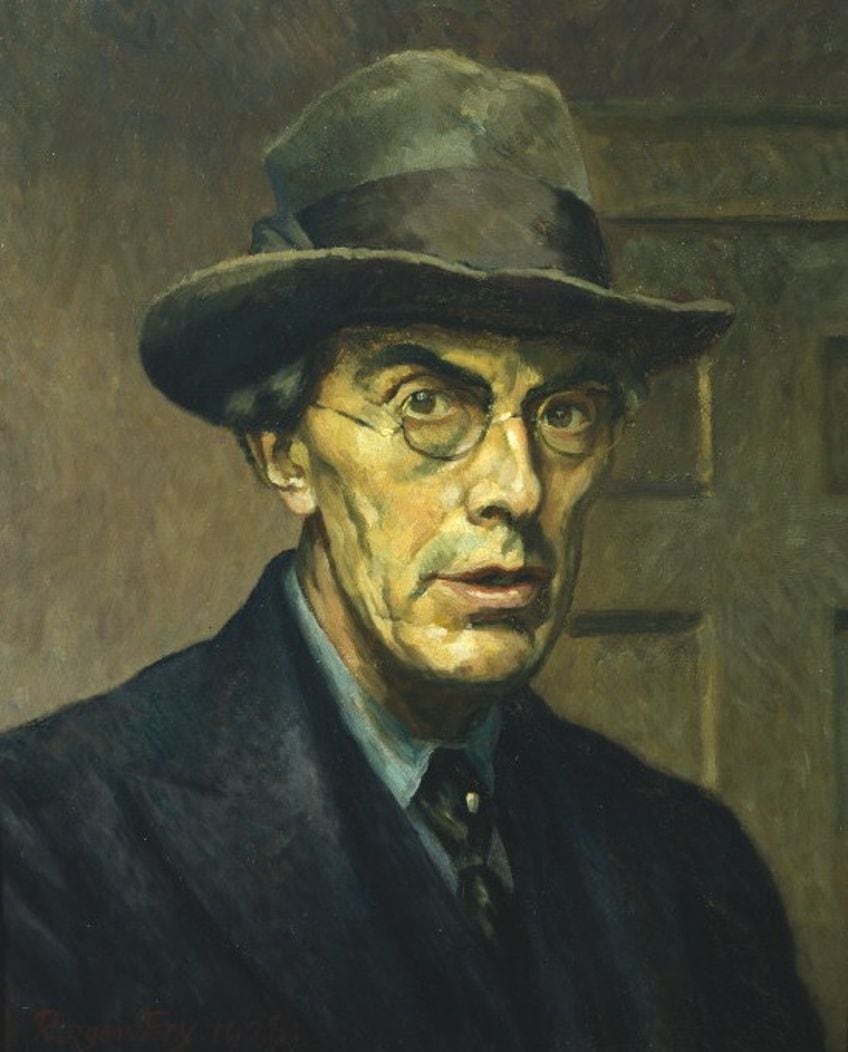

Roger Fry (1866 – 1934)

| Date of Birth | 14 December 1866 |

| Date of Death | 9 September 1934 |

| Place of Birth | London, United Kingdom |

| Nationality | British |

In the early part of the 20th century, British painter, curator, and critic, Roger Fry formulated an early modernist approach to interpretation similar to Formalism. In 1910, Fry presented Manet and the Post-Impressionists, an exhibition at the Grafton Gallery in London which ran from 8 November to 15 January the following year. Featuring Avant Garde artworks by Manet, Cezanne, and Gauguin, the exhibition was met with rage and ridicule. These artworks challenged the prevailing conventions of mimetic art. Fry was attempting to posit the post-Impressionists as a return to the basic ideas of formal design which he argued had prevailed in the centuries prior to the artistic pursuit of the illusion of reality. Fry’s system of analysis of form observed the formal quality of a work of art through its method of manufacture.

Fry understood Formalism as a methodological lens, judging an artwork not by its degree of realism, but by its level of visual expression.

Clive Bell (1881 – 1964)

| Date of Birth | 16 September 1881 |

| Date of Death | 17 September 1964 |

| Place of Birth | Berkshire, United Kingdom |

| Nationality | British |

In his book Art (1914), English art critic Clive Bell established his own brand of the Formalistic theory of art. Bell agreed with Kant that the unique quality of the art was ‘significant form’. Significant form referred to the arrangements of lines, colors, and shapes, and as Kant had suggested, these arrangements led to the experience of aesthetic emotions such as beauty. Bell surmised that the purpose of art was to evoke aesthetic emotion through significant form. Bell had admired non-Western and pre-Renaissance artworks, which instead of merely copying the appearance of nature were free to use line, color, and shape, towards the creation of significant form.

Some recent artists such as Paul Cézanne had, in Bell’s opinion, rediscovered the true purpose of art, evoking aesthetic emotion.

Clement Greenberg (1909 – 1994)

| Date of Birth | 16 January 1909 |

| Date of Death | 7 May 1994 |

| Place of Birth | New York City, United States |

| Nationality | American |

In the mid-20th century, the American art critic Clement Greenberg explored Formalism as an emphasis on formal elements like line, color, and composition instead of subject matter. Thanks in part to Greenberg, Formalism art became extremely prominent in post-World War II art. He was arguably Formalism’s most well-known advocate and approached formal analysis with unprecedented detail and rigor. Greenberg used a Formalistic approach to champion the artists he worked with, including the Abstract Expressionists. Greenberg’s iconic essay Modernist Painting (1960) used Jackson Pollock’s paintings as emblems of Formalism.

For Greenberg, Pollock’s style was an ideal example of the manipulation of pure form.

Formalism and Modernism

Formal art goes by many names such as Avant-Garde, Modern art, or Abstract art. The categories of formal analysis emerged along with Modernism in North America and Europe. Formalism in art could be seen as the philosophical origin from which various groups of Modern artists such as the Impressionists explored the nature of perception. Their art rejected the notion of painting as simply an illusion of reality. As artists explored the new understanding of individual perception, there was a gradual shift towards abstraction. As Modern artists were interested in scenes of everyday life, of everyday people going about their daily routines, a growing middle-class audience began to see their culture reflected in art.

Formalism, which was a basic and instinctive form of analysis, responded to a growing desire for tools of interpretation to approach new kinds of images.

Modernist painting was perfectly suited to be analyzed based on color, line, composition, and other such formalist terms. The rise of the critical approach of Formalism is intricately connected to the rise of Abstraction in the 19th century. Formalism in art was ideal for analyzing artworks by modern artists such as Manet, Courbet, or Monet. These artists’ methods were not academic. Their brushstrokes were more painterly and more rapid. As representational motives vanished from the canvas, artists began to experiment with compositional elements such as line, color, shape, and texture. This led to the canonization of what we know as Modern painting.

Examples of Formalist Artworks

As a critical movement in Modern art, the Formalism movement produced many noteworthy artworks during its time. Below, we will be taking a look at a few of these important paintings, along with their artists.

Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket (1875) by James McNeill Whistler

| Artist | James McNeill Whistler (1834 – 1903) |

| Date | 1875 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (cm) | 60.3 x 46.6 |

| Where It Is Housed | Detroit Institute of Arts, Michigan, United States |

One of the most famous examples of Formalism in art is James McNeill Whistler’s Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket (1875). The painting portrays a night of fireworks at London’s Cremorne Gardens. The firework’s orange flecks sparkle and light up the darkness of the dark blue-greens of the river. As a result of Whistler’s preference for thin layers of paint, the scene has a translucent ghostliness, departing from figurative accuracy, and reflecting Whistler’s interest in evocative abstraction.

The first public exhibition of Whistler’s oil on panel painting Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket was in 1877.

Subsequently, the famous Victorian art critic John Ruskin publicly charged Whistler with “flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face”. Whistler sued Ruskin, making the painting the subject of an iconic libel case. Over the course of the trial, Whistler would articulate a defense insisting that art requires no purpose other than its intrinsic beauty. an outrageous concept to the critic and art lovers of Victorian England. Whistler’s defense of his Nocturne would come to stand as a standard defense of Modern art. It was the last in this series and became an influential exemplar of a Formalist approach.

Rejecting the notion that his Nocturne was an attempt to accurately depict a view of a specific place, this work reflects Whistler’s view that a painting’s formal elements were more important than an accurate representation. The asymmetric composition, the calligraphic character of the brushstrokes, and the way the colors complement each other, all amount to what Whistler called an “artistic arrangement” that was simply intended to be enjoyed.

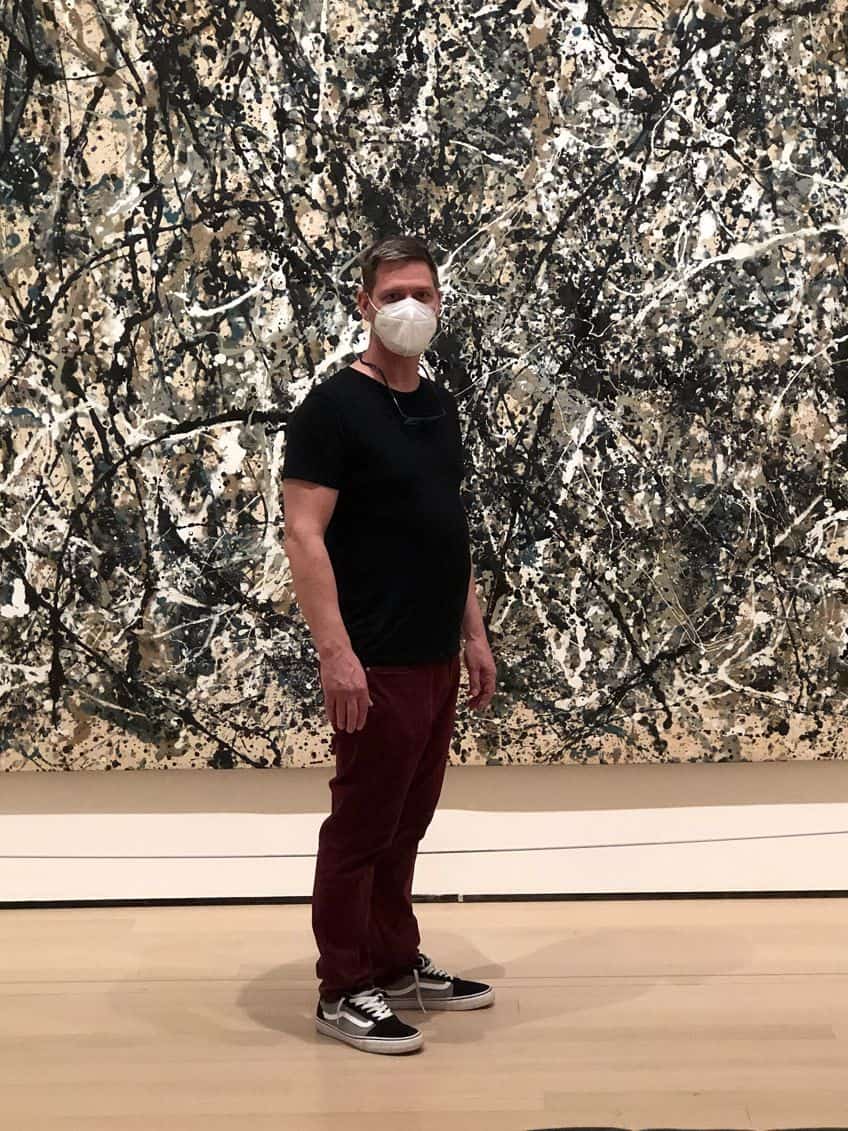

Number 31 (1950) by Jackson Pollock

| Artist | Jackson Pollock (1912 – 1956) |

| Date | 1950 |

| Medium | Oil and enamel paint on canvas |

| Dimensions (cm) | 269.5 x 530.8 |

| Where It Is Housed | Museum of Modern Art, New York City, United States |

One of the most famous examples of Formal art is Jackson Pollock’s pioneering Abstract Expressionist, work Number 31 (1950). A formalist analysis of this painting would be based on an observation of its colors, shapes, lines, brushwork, composition, and texture. In Number 31 the surface is covered with interlaced lines which are random and vigorous. There is no center, no deep space, and no solid or dynamic mass, but a high contrast of black and white accentuates the all-over composition and business of the lines.

We could conclude that the visual expression is unrestricted, active, anxious, and intense.

Blue, Green, and Brown (1951) by Mark Rothko

| Artist | Mark Rothko (1903 – 1970) |

| Date | 1951 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | Unknown |

| Where It Is Housed | Unknown |

In American artist Mark Rothko’s Blue, Green, and Brown (1951), the use of line is saturated, softer, and calmer. The balanced horizontal bands are divided into two registers on the vertical surface. The composition is so calm the bands seem to be floating. The abstracted use of pigment draws the viewer towards the texture of the surface, creating an absorbing, enveloping experience. The upper band is larger, evoking a sky looming over the earth, a dim light, perhaps at dusk with the blues consuming the browns and greens.

The mood is dark and melancholic.

Hommage to the Square (1959) by Joseph Albers

| Artist | Joseph Albers (1888 – 1976) |

| Date | 1959 |

| Medium | Oil on masonite |

| Dimensions (cm) | 120.6 x 120.6 |

| Where It Is Housed | Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York City, United States |

German artist Joseph Albers’ series Hommage to the Square (1959) undoubtedly comes from a formalist approach. The painting shows a series of concentric squares with varying color relationships. The paintings have no narrative. They are not necessarily rooted in a historical context. They cannot possibly be aiming to convey any feeling the artist may have experienced.

These are just squares with varying colors, soliciting the viewer’s optical response to the formal components.

Flawed Formations

As with most prominent theories, there has been no shortage of criticism of formal analysis. Anti-Formalism emerged soon after Formalism’s initial attempts at canonization. Critics disputed Formalism’s alleged historical function of art and demanded more nuanced descriptions of form. The toughest challenges to Formalism were arguably Conceptual art and Postmodernism. Faced with artworks from artists such as Marcel Duchamp and Andy Warhol, Formalism had no answers to the question of concept which would eventually dominate contemporary art. Postmodernism’s gritty critical reflection on the socio-political mechanisms of a globalized art world dismantled meta-narratives and the Eurocentric myth of universal truth. Eventually, contemporary artists outgrew Postmodernism as well, seeking entirely new appreciations of form, content, and meaning.

More recently, political and social concerns have gained more importance in critical and artistic methods. Strictly aesthetic doctrines have lost their appeal.

Formalistic theory has a long history but culturally, it is not a neutral method for analyzing art. It resulted from and best accompanies Modernism – a specific cultural moment that does not encompass all art. Formalism is indeed incredibly useful in the description of completely abstract works of art. But outside of this context, Formalistic theory has its limitations. Formalism suggests that these terms that describe observations such as composition, color, balance, texture line, etc., are elements of all artworks. But none of this terminology is non-Western, any older than 100 years old, and most of it was developed in the 20th century to critique and teach Modern art. Therefore, it is best to understand Formalism as a tool best employed when framed by an awareness of its historical and cultural context.

An application of a formal analysis on African American artist Glenn Ligon’s work Negro Sunshine (2015) for example, would not suffice. Simply noting that this artwork is a light work, that it measures 91.4 by 487.7 centimeters, is made of paint and neon, with wires connecting to what looks like batteries on the floor misses the point. The artwork surely does evoke aesthetic emotion with the warm, yellow glow of its neon lights spelling out the phrase Negro Sunshine in a dimly lit gallery space. But given America’s racial history, and the contemporary context, the work clearly amounts to more than its formal elements. The artist wants us to think about more than just how this sculpture looks.

In its avoidance of any other forms of judgment, formal analysis would come nowhere near properly interpreting the meaning behind this work. Its sterile inventory of the artwork results in an unemotional and apathetic engagement with the art. It is a good place to start when interpreting art, but it is not always a good place to stop. Analyzing and appreciating most art based on its formal qualities would entail neglecting significant issues of social, political, economic, historical, and psychological context. As life has always been part of art, Formalism has never managed to fully separate art from life’s concerns. Had it done so, it might have impoverished arts richness. Formal analysis contributes to the anatomization of an artwork, but it can result in a dispassionate description of the compositional facts of an artwork. Nonetheless, Formalism has survived and continues to adapt to new contexts.

It has continued to influence most critical approaches and contemporary artistic styles because it appeals to such a basic part of aesthetic experience. In 2014 Formalism’s latest revival appeared in the form of “Zombie Formalism” a term coined by art critic Walter Robinson elaborating: “‘Formalism’ because this art involves a straightforward, reductive, essentialist method of making a painting…and ‘Zombie’ because it brings back to life the discarded aesthetics of Clement Greenberg.”

Formalism in Summary

The premise behind Formalism has been that since there was no longer any iconography or symbology to decipher or decode, a viewer would not require an upper-class education or academic background to enjoy these artworks. Formal analysis entailed a mere inventory of formal qualities like the texture of the paint, a sculpted surface, or the way colors and lines interact. Since anyone could perform such an analysis on any art object, Formalism was said to make art more accessible. As such formal analysis is considered a foundation of interpretation and a starting point for all deeper analyses. Even though a formal analysis only consists of a purely visual description of the work, it is still a powerful tool for art historians and artists to understand the visual aspects of a work of art. Visual elements are after all the first impression and therefore an essential part of a work of art.

The simplification of artistic interpretation is tempting. Just listing observations would be a convenient answer to the question of what art actually is. But while an effective, trans-historical set of criteria for the analysis of art is incredibly attractive, Formalism does not necessarily fit that description. Observation of form is instinctive, but it is also accompanied by the history of an artwork, knowledge of who made it, or how it is made.

Nonetheless, the formalistic theory of art offers the advantage of elevating art above everyday social and utilitarian concerns. One of the most valuable lessons of Formalist art theory is that an artwork should be intended to be experienced and enjoyed simply for what it is, and that form and its analysis should give rise only to aesthetic emotion, or the sublime experience of beauty.

Frequently Asked Questions

Did Formalism Always Exist?

Formalism didn’t always exist, as other forms of visual analysis, such as iconography and symbolism, predated Formalism. These methods required prior knowledge of history or semiotics. Until the late Renaissance in the 17th century, taking an inventory of an artwork’s visual properties was not a common way to interpret art.

What Is the Difference Between a Strong Formal Analysis and a Weak Formal Analysis?

A weak formal analysis uses the visual properties of artwork as the starting point for reading an artwork. A strong formal analysis uses the visual properties of artwork as the entire analysis, adhering strictly to the doctrine of Formalism.

Which Movement Did James McNeill Whistler Belong To?

James McNeill Whistler was considered a leading figure in the development of Modernism. His landscapes were important in both the aesthetic philosophy of Formalism, and in launching Tonalism as a movement.

Liam Davis is an experienced art historian with demonstrated experience in the industry. After graduating from the Academy of Art History with a bachelor’s degree, Liam worked for many years as a copywriter for various art magazines and online art galleries. He also worked as an art curator for an art gallery in Illinois before working now as editor-in-chief for artfilemagazine.com. Liam’s passion is, aside from sculptures from the Roman and Greek periods, cave paintings, and neolithic art.

Learn more about Liam Davis and about us.

Cite this Article

Liam, Davis, “Formalism Art – A Unique Method for Analyzing Art.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. September 27, 2023. URL: https://artfilemagazine.com/formalism-art/

Davis, L. (2023, 27 September). Formalism Art – A Unique Method for Analyzing Art. artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. https://artfilemagazine.com/formalism-art/

Davis, Liam. “Formalism Art – A Unique Method for Analyzing Art.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source, September 27, 2023. https://artfilemagazine.com/formalism-art/.