South American Art – An In-Depth History and Analysis

Whereas South American art refers to the art made exclusively in South America, Latin American art is the term used to characterize the artworks produced in South America, Mexico, the Caribbean, and Central America. The Latin arts can be traced back to various indigenous cultures that thrived in the region before the 16th-century colonization by the Europeans. Latino artwork was primarily influenced by the religious beliefs and practices of these indigenous cultures. To learn more about Latin artwork, we will be taking a look at Latino art history and the various forms that it takes, such as Latin American painting and photography.

The History of Latin American Art

The Latin and South American artworks created before European colonization are referred to as Pre-Columbian artworks. The distinct Mestizo style that arose after colonization is a mixture of European, Amerindian, and African cultures. This new style would come to define Latino art from the colonial period up to the modern era. Let’s take a deeper look at the progression of Latino art history.

The Latin Arts of the Colonial Period

Following the colonization of the region, a Christian-based style of Latin artwork emerged known as Indo-Christian art, which was a blend of Indigenous and European traditions (influenced by the Christian doctrines introduced by the Augustinian, Dominican, and Franciscan friars). Latin American painting was influenced by Portuguese, Spanish, French, and Dutch Baroque art. The very first school of painting in the Americas that featured elements of the European style was known as the Cuzco School. Quechua-speaking indigenous tribes were instructed on how to portray religious imagery in the Renaissance and classical styles by Spanish art teachers in the 17th and 18th centuries.

Casta paintings, a type of painting that represented the system of racial hierarchy that existed at the time, were produced by both Mexican and Spanish artists in the 18th century.

It was a form that was almost entirely exclusive to Mexico, although one Peruvian set has been found. Unlike the Latin American paintings from previous eras that were more religious in subject matter, these paintings were regarded as secular Latin artworks. The only known exception is a singular casta painting that features the Mexican religious figure, the Virgin of Guadalupe, which was produced by Luis de Mena – a little-known painter of the time. It was a popular form of Latino art and was produced by several of the most noted artists in Mexico, such as Miguel Cabrera.

The majority of these paintings were produced as sets comprising multiple canvases featuring one family group on each canvas. However, there were also a few produced that portrayed the complete racial hierarchy, from the slaves at the bottom to the nobility at the top. The families were depicted in idealized groupings, with each family comprised of a mother and father of different races, as well as children of a third race. After these state-ordained racial categories were abolished following Mexico’s independence in 1821, the production of casta paintings came to a sudden halt. The Dutch captured Brazil in the 17th century, which had been a Portuguese colony up to that point. Portrayals of the various Brazilian indigenous peoples were produced by Albert Eckhout, a Dutch artist, during that period.

The Spanish crown approved a series of scientific expeditions to explore Spanish America and document its fauna and flora. José Celestino Mutis, a Spanish horticulturist and doctor, led an expedition to the northern region of South America in 1784. Over 5,000 color drawings of the region’s flora and fauna were produced by the local Ecuadorian Indian artists. These scientific illustrations marked a departure from the traditionally religious subject matter of the preceding eras.

Alexander von Humboldt then explored and recorded his scientific findings of Spanish America over a five-year period from 1799 until 1804, in which he documented the lifestyles and attire of the local tribes. The works of travelers who depicted and documented local scenes as well as further scientific expeditions in the 19th century were all influenced by Humboldt’s initial efforts in the field. The Academy of San Alejandro in Havana is the oldest institute of Latin American art and was founded by Alejandro Ramírez and Jean Baptiste Vermay in 1818.

It is usually those individuals that have studied in academic art history departments who end up writing about Latino art history.

Yet, due to the concept of “visual culture”, many people from other disciplines and fields of study have begun to write another chapter in the annals of Latin arts. For many years, scholars were focused on either the artworks of the Pre-Columbian era or those produced in the modern era. However, the works produced in the Colonial period and the 19th century have more recently become the subject of their focus.

Latino Art and Modernism

Modernism is a Western art movement that is characterized by its abandonment of traditional classical forms. In South American art, this style holds an ambiguous position. As all of the regions developed urban centers at different time periods, the emergence of Modernism in Latin America is hard to pinpoint. Some embraced Modernism, while others vehemently opposed it. In general, the Southern Cone countries were more susceptible to foreign influences, whereas nations with a greater indigenous presence, such as Peru, Mexico, Bolivia, and Ecuador, were more averse to European culture.

Modern Art Week was a milestone event for Modernism, which took place in Sao Paulo in 1922, signifying the start of the Modernismo movement in Brazil. While a number of different Brazilian artists were producing modernist works before this event, it brought the movement together, defined it, and presented it to Brazilian society.

Latin Artwork and the Constructivist Movement

Generally speaking, the creative Eurocentrism synonymous with the colonial era started to wane in the early 20th century, as Latin American artists became more aware of their distinct identities and chose to chart their own course. Constructivism influenced Latin American art from the early 20th century onward when It spread rapidly from Russia through Europe, and eventually to Latin America. The constructivist movement was introduced to Latin America by Manuel Rendón and Joaquin Torres Garcia. Garcia returned to Uruguay in 1934 following a long and productive career in the United States and Europe, where he both supported Constructivism and expanded it into Universal Constructivism – a distinctly Uruguayan movement. In 1935, he formed the Asociación de Arte Constructivo in Montevideo as a Latin arts center and exhibition venue for his group, gathering a group of established peers and new artists as adherents.

Due to a lack of funds, this venue was closed in 1940, so in 1943, he founded the Taller Torres-Garca, a training institution and workshop that ran until 1962.

South American Art Muralism

Muralism is a prominent Latin American artistic movement, best exemplified by the Mexican muralists David Alfaro Siqueiros, Diego Rivera, Rufino Tamayo, and José Clemente Orozco. Muralists in Chile included Pedro Nel Gómez and José Venturelli, while Muralism in Colombia was popularized by Santiago Martinez Delgado, and in Venezuela, it was promoted by Gabriel Bracho. José Vela Zanetti, a Spanish migrant in the Dominican Republic, was a prodigious muralist, producing over 100 murals around the country.

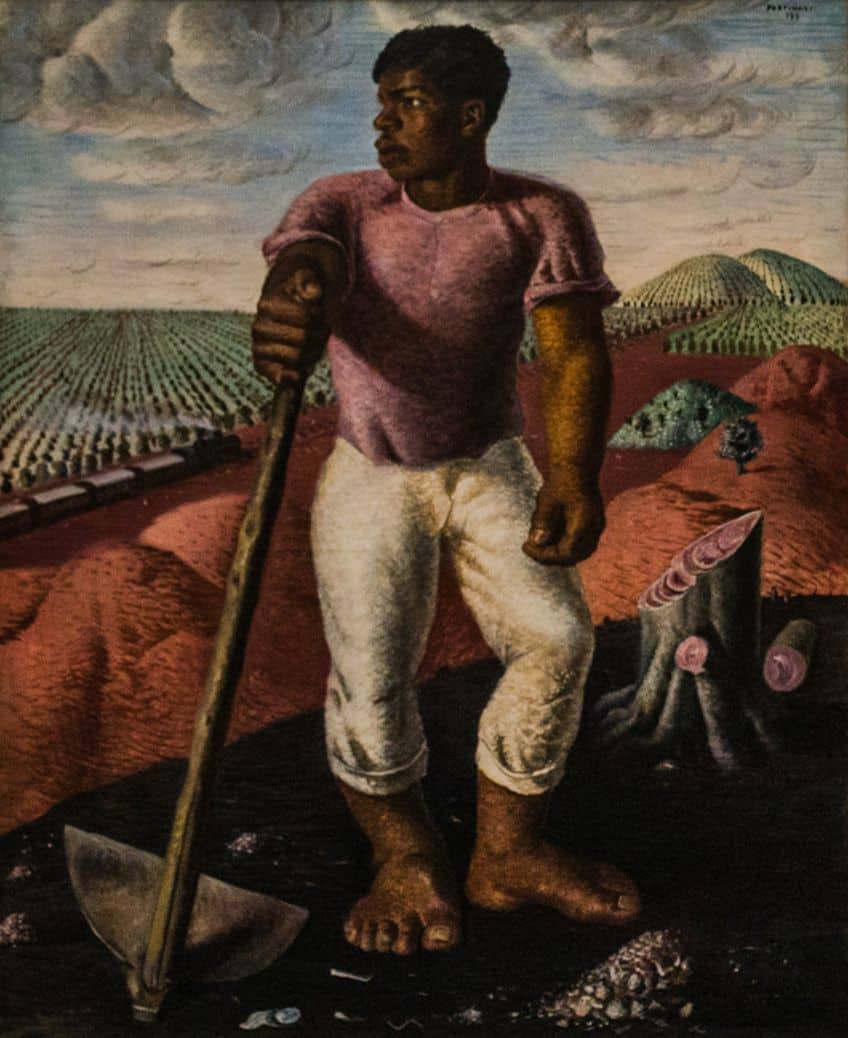

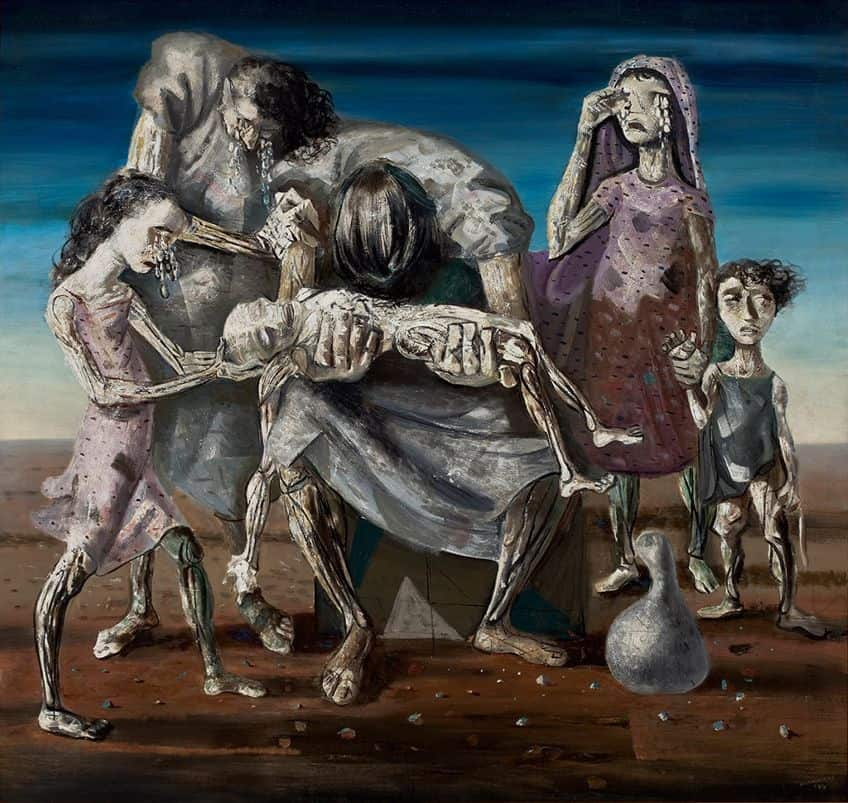

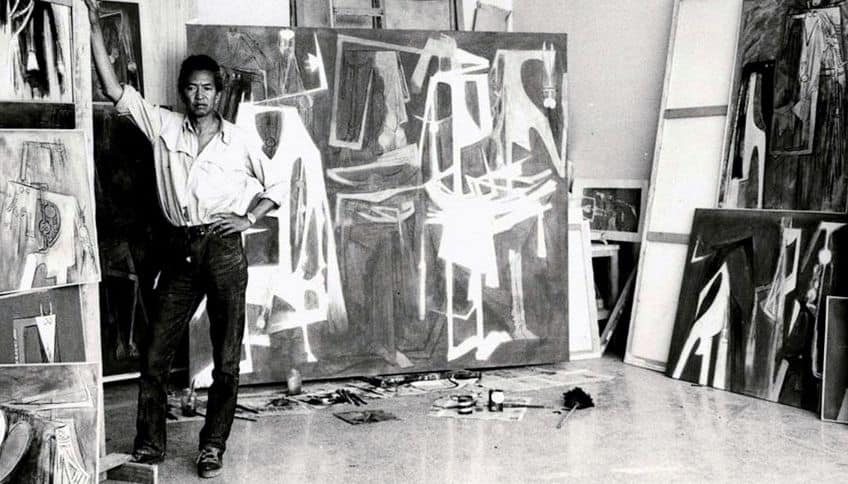

Artists such as Brazilian Candido Portinari, Ecuadorian Oswaldo Guayasamn, and Miguel Alandia Pantoja from Bolivia are also renowned. Significant muralist works of art can be seen throughout Mexico, Colombia, San Francisco, New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, and Philadelphia. Muralism in Mexico enjoyed a level of respect and impact in other nations that no other art movement in America had ever achieved. Muralism offers a distinct art style for Latin American artists to express themselves politically and culturally, typically focused on social justice issues connected to their indigenous cultures.

The Rupture Generation

Rupture Generation was the name given to a 1960s Mexican art trend in which young artists rebelled against the dominant national style of Muralism. This movement, distinguished by figurative and expressionistic styles, sprang from the younger artists’ need for increased artistic freedom. The Rupture movement is recognized as having been started by Mexican artist José Luis Cuevas. Mexican muralists were criticized by Cuevas for being overtly political, labeling it “cheap journalism” instead of art, in a publication titled La Cortina del Nopal (1958).

Rafael Coronel, José Luis Cuevas, and Alberto Gironella were some of the more notable artists of the Rupture Generation.

Nueva Presencia

Francisco Icaza and Arnold Belkin co-founded Nueva Presencia in the early 1960s. The Nueva Presencia artists embraced an anti-aesthetic rejection of modern art movements and a belief that the artist had a social obligation to react to World War II atrocities like the atomic bomb and the Holocaust. The Nueva Presencia manifesto, which was printed in the debut issue of the literary review that bore the same name, detailed their beliefs as a movement. They felt that no one should be apathetic to social order, particularly artists, and the movement included members such as Artemio Sepúlveda, Emilio Ortiz, Leonel Góngora, Francisco Corzas, and José Muñoz.

Surrealism in Latin American Painting

After visiting Mexico in 1938, André Breton, the father of Surrealism, declared it to be the quintessential example of a Surrealist country. Surrealism, a post-World War I European art movement, had a significant effect on Latin American art, and it is here that Mestizo culture, the remnant of European conquest over indigenous cultures, represents contradiction – a core principle of Surrealism. Frida Kahlo, a well-known Mexican artist, produced self-portraits and portrayals of indigenous Mexican society in a style that blended Symbolism, Realism, and Surrealism. She did not personally view herself as a Surrealist, though, as she did not portray her dreams, but instead, her reality. The Surrealists Leonora Carrington and Remedios Varo are a few other well-known female artists who worked and lived in Mexico, although neither was originally born in Mexico.

Surrealists also include the Chilean painters Mario Carreo Morales, Roberto Matta, and Nemesio Antnez, the Cuban artist Wifredo Lam, and the Argentinean artist Roberto Aizenberg.

Styles and Trends of Latin Arts

Latin American art has been largely shaped by the classical European art movements for a very long time. Many Latin American painters continued to get their education in the conventional 19th-century fashion far into the 20th century, which contributed to a continuing focus on figurative work. Additionally, political and social critique has often been conveyed through South American art.

Figuration

Because of the broad scope of figuration, the work regularly encompasses a variety of styles, including Pop art, Realism, Expressionism, and Surrealism, to name just a few. While these Latino artists are dealing with problems ranging from the intimate to the political, many of them have a common interest in indigenous concerns and the impact of European cultural imperialism. Otra Figuración, an Argentine artist collective and community founded in 1961, was one committed to figuration. Ernesto Deira, Rómulo Macció, Jorge de la Vega, and Luis Felipe Noé shared a studio and lived together in Buenos Aires. These artists produced work in an expressive abstract figurative style using vibrant colors and collages.

Although Otra Figuración and Nueva Presencia were contemporaries, there was no formal communication between the two movements.

Sociopolitical Parody and Critique

José Guadalupe Posada, a Mexican graphic artist, depicted scathing pictures of Mexican aristocracy as skeletons This was done before the Mexican Revolution, and it had a big influence on later painters like Diego Rivera. Parodying Old Master works, particularly those of the Spanish court made by Diego Velázquez in the 17th century, is a prevalent trend among Latin American figurative painters. These parodies have a dual function by referencing Latin American cultural and artistic heritage while also criticizing the legacy of European cultural colonialism in Latin American states. Alberto Gironella and Fernando Botero are two well-known artists that used this technique often.

Fernando Botero, a Colombian figurative artist whose artwork displays unusual “puffy” figures in varied settings dealing with issues of war, power, and social challenges, has utilized this style to draw comparisons between modern ruling authorities and the Spanish monarchy. A notable early example is his painting The Presidential Family (1967). This Latin American painting includes a self-portrait of Botero standing behind a big canvas, recalling Diego Velázquez’s Spanish court masterpiece Las Meninas (1656). The “puffy” presidential family, dressed in stylish regalia and peering dryly out of the painting, seem socially superior, highlighting the social inequalities. Botero claims that his “puffy” images are not meant to be amusing.

He also produced a striking series of paintings based on pictures of the U.S. military torture of Iraqi captives at Abu Ghraib jail. Alberto Gironella, a Mexican artist and collagist whose style combines aspects of Pop art and Surrealism, also created parodies of official Spanish royal paintings. He produced numerous variations of Queen Mariana (1652) by Velásquez. Gironella’s parodies use subversive imagery to criticize Spanish authority in Mexico. Mariana is seen in La Reina de Los Yugos (1981) wearing a skirt constructed of upside-down ox yokes, symbolizing both Spanish supremacies over Mexico’s native citizens and the peoples’ defiance of Spanish power. Sandra Ramos’ Latin American paintings, installations, etchings, collages, and digital animation typically address taboo topics in modern Cuban culture, such as mass migration, racism, social inequality, and communism.

Photography

Photographers documented native peoples as well as various societal types, such as Argentina’s gauchos. Numerous Latin Americans have contributed significantly to modern photography. José Bassit and Guy Veloso capture Brazilian religion on film. Guillermo Kahlo captured Mexican colonial architecture and engineering, such as the Metlac railway bridge. Agustin Casasola photographed several shots of the Mexican Revolution and amassed a large archive of Mexican photographs. Among the other notable photographers are Graciela Iturbide from Mexico, Martin Chambi from Peru, and Alberto Korda from Cuba, best known for his iconic portrait, Che Guevara (1960). Mario Testino is a well-known fashion photographer from Peru.

In addition, a large number of non-Latin American photographers, like Edward Weston and Tina Modotti, have concentrated on documenting the region, particularly in Mexico. Mara Cristina Orive, a Guatemalan citizen, has collaborated with Sara Facio in Argentina.

Notable Latin American Artists

Latin American artists were mostly excluded from pervasive interpretations of art history. This list of artists demonstrates that many of the innovative, significant Latino artists in the 20th century were not limited to the area but were, in fact, quite global. Here are a few notable Latin American Artists that helped bring South American art into the spotlight.

Wifredo Lam (1902 – 1982)

| Artist Name | Wilfredo Lam |

| Nationality | Cuban |

| Date of Birth | 8 December 1902 |

| Date of Death | 11 September 1982 |

| Place of Birth | Sagua La Grande, Cuba |

| Notable Artworks | ● The Jungle (1943) ● Femme Cheval (1943) ● Pleni Luna (1974) |

Wifredo Lam was an artist who experimented with creative techniques such as Cubism and Surrealism while traveling around Europe, as well as topics relating to his mixed European, Chinese, Indigenous, and Afro-Cuban spiritual ancestry. Lam’s work resembled Surrealism during the early 1930s, and in 1938, he flew to Paris to study with Pablo Picasso.

In an ironic twist, Picasso’s preoccupation with so-called “primitive” societies inspired Lam to infuse his own Caribbean cultural heritage into his work, but with a keen knowledge of the cultural hierarchies maintained by the European avant-garde.

Ana Mendieta (1948 – 1985)

| Artist Name | Ana Mendieta |

| Nationality | Cuban-American |

| Date of Birth | 18 November 1948 |

| Date of Death | 8 September 1985 |

| Place of Birth | Havana, Cuba |

| Notable Artworks | ● Rape Scene (1973) ● Silueta Series (1974) ● Untitled (1984) |

Ana Mendieta’s transdisciplinary approach challenges fixed markers of sexual orientation, sexual freedom, and humanity’s relationship to the Earth. She spent part of her youth in an orphanage before attending the University of Iowa to study art. Mendieta started utilizing her own body through performances at this early stage.

Her multimodal approach included photography and video works that addressed the complex relationships between bodies, the Earth, and mortality.

Feliciano Centurión (1962 – 1996)

| Artist Name | Feliciano Centurión |

| Nationality | Paraguayan |

| Date of Birth | 20 March 1962 |

| Date of Death | 7 November 1996 |

| Place of Birth | San Ignacio, Paraguay |

| Notable Artworks | ● Ducks (1993) ● Florece mi Corazón (1994) ● Ciervo (1994) |

Feliciano Centurión’s textile pieces from the 1980s and 1990s solidify his artwork in worldwide Gay rights discourse, focusing on subjects such as decay, love, vulnerability, and empathy. Centurión went to Buenos Aires in the early 1980s, when he became a key member of the city’s Arte Light group, which tried to oppose the dictatorship’s repressive cultural influences through play, joy, comedy, and innovation in artmaking. Centurión’s artworks included household items such as pillows, blankets, and other found fabrics, which he embroidered with lyrical words and graphic motifs such as animals as well as other indigenous Guaran themes.

Latin American art refers to creative traditions that arose in Central America, Mesoamerica, and South America following interaction with the Portuguese and Spanish in 1492, and have continued until the current day. While art during the colonial period was heavily influenced by the Spanish, in more modern times, the Latin arts have embraced their heritage and traditions and begun to reincorporate them into their works. Today, Latino art encompasses not only art made by those living within the region, but of Latin Americans living across the world.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Latino Art?

It refers to the art created by South American artists and often incorporates traditional Latin American motifs and techniques. However, it is not limited to art created in South and Mesoamerica, but also in North America and anywhere else that Latinos have settled. South American art is distinguished by a rich and diversified cultural legacy influenced by indigenous populations, colonial rule, and globalization. Today, it is a blend of many varying influences.

What Characterizes South American Art?

South American indigenous people have a long tradition of producing art that represents their spiritual beliefs, stories, and daily lives. These art styles frequently integrate symbolic motifs and natural materials, such as pottery, textiles, stone, wood, and bone sculptures. The presence of Portuguese and Spanish invaders in South America in the 16th century had a massive impact on its art. Baroque, Renaissance, and Mannerism styles were brought and merged with indigenous art forms to produce a one-of-a-kind combination of art and architecture. Many South American artists utilize their art to make political and social statements.

Liam Davis is an experienced art historian with demonstrated experience in the industry. After graduating from the Academy of Art History with a bachelor’s degree, Liam worked for many years as a copywriter for various art magazines and online art galleries. He also worked as an art curator for an art gallery in Illinois before working now as editor-in-chief for artfilemagazine.com. Liam’s passion is, aside from sculptures from the Roman and Greek periods, cave paintings, and neolithic art.

Learn more about Liam Davis and about us.

Cite this Article

Liam, Davis, “South American Art – An In-Depth History and Analysis.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. September 28, 2023. URL: https://artfilemagazine.com/south-american-art/

Davis, L. (2023, 28 September). South American Art – An In-Depth History and Analysis. artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source. https://artfilemagazine.com/south-american-art/

Davis, Liam. “South American Art – An In-Depth History and Analysis.” artfilemagazine – Your Online Art Source, September 28, 2023. https://artfilemagazine.com/south-american-art/.