Art Periods and Movements – Our Insanely Wide-Ranging Guide

We, as humans, have expressed ourselves creatively since prehistoric times, from crushing ochre to create rock art to Banksy spray painting walls to create street art. We have compiled an overview of art historical periods and movements, explaining each one in summary and including important artists and artworks. It is important to remember that this chronology is not linear, that periods and movements may overlap, and that artists were sometimes part of more than one movement. There are numerous cultures around the world and art movements, and we may miss a few, but we have tried to include a summary of as many notable ones as possible. For more in-depth information, we encourage you to read some of our other articles.

The Difference Between Art Eras, Art Periods, and Movements

The term “art period” refers to a section of time that includes various artists and their artworks and they are usually arranged by art historians after the period has passed. Therefore, more than a few art movements can be held within a period. “Art eras” refer to extended time periods. The Upper Late Paleolithic is a good example of an era that lasted for about 20,000 years. An “art movement” refers to a group of artists that have a shared style, aim, or idea, sometimes forming clubs that have a representative and specific philosophy.

Art History Timeline

Understanding the art history timeline can help us to comprehend the background history that contributed to the various art style periods and movements. Below is a table of the various art periods and movements that form the art history timeline.

Ancient/Classical Art Periods and Movements

| Art Periods and Movements | Dates | Characteristics |

| Prehistoric Art |

| Before written records were kept. Examples are rock carvings, paintings, engravings, stone arrangements, and sculptures. |

| Asian Art | 38,000 BCE – Present | Asian art encompasses the art made by cultures from China, India, Indonesia, Japan, Korea, and the Russian Far East. |

| Traditional African Art | 23,000 BCE – Present | African art is made by various cultures on the African continent with different styles. |

| The Ancient Near East

|

| Stone relief with tales and warrior art. |

| Egyptian Art |

| Art focused on the gods and the afterlife as depicted in pyramids, tombs, and temples. |

| Greek Bronze Age |

| The height of the Bronze Age of Greece included fresco murals and painted ceramics that depicted landscapes, humans and animals. |

| Pre-Columbian Art | 1,200 BCE – 1,535 CE | The art of America and its islands was created before the arrival of Columbus |

| Ancient Greek Art |

| Greek idealism and the perfection of body proportions. |

| Etruscan Art | 700 – 509 BCE | Etruscan art was a combination of Greek and Roman styles. |

| Ancient Roman Art | 735 BCE – 337 CE | Commemoration and Realism. The depiction of realistic features, rather than idealized proportions. |

| Early Christian Art | From the beginning of Christianity – 525 CE | The emergence of Christian imagery and sculpture. |

| Middle Ages (Medieval Art) |

| In Europe, early Medieval art was a mixture of the Roman artistic tradition and Northern European culture, as well as the early Christian church. |

| Renaissance |

| Greatly influenced by the ideas of the ancient Greeks and Romans, with an emphasis on balance and proportion. |

| Mannerism | 1527 – 1580 | Following the footsteps of Renaissance realism, but with exaggerated details and emphasis on figural composition. |

| Baroque | 1600 – 1750 | Art and architecture were over-the-top and ornate, and the artistic style was dramatic and complex. |

| Rococo | 1702 – 1780 | Theatrical, light, whimsical works painted in pastel colors and focusing on natural shapes and curves. |

| Neoclassicism | 1750 – 1850 | A resurgence of the character and styles of classical antiquity. |

| Romanticism | 1780 – 1850 | Romanticism commemorated intuition and imagination, valuing originality and emotion. |

| Realism | 1848 – 1900 | Turned away from idealism and painted events and subjects from real life in a naturalistic way. |

| Photography |

| The invention of photographic images was initially used for practical purposes and eventually broadened in artistic expression. |

| Arts & Crafts Movement | 1860 – 1920 | The movement’s artists were linked with decorative arts and architecture rather than sculpture and painting of “high” art and stressed the importance of functionality in design. |

| Art Nouveau | 1890 – 1905 | Linear contours were important, and artists were inspired by forms found in nature, flattening and abstracting subjects to create elegant flowing patterns and shapes. |

| Art Deco | 1900 – 1945 | Art Deco was characterized by geometric, sleek symmetrical forms that were stylized and elegant. Visual art pieces included both mass-produced and extravagant works that were individually made. |

Modern Art Movements

| Art Periods and Movements | Dates | Characteristics |

| Impressionism | 1862 – 1892 | Artists painted an impression of what they saw in everyday life depicted with loose, thick brushstrokes and an emphasis on color and light. |

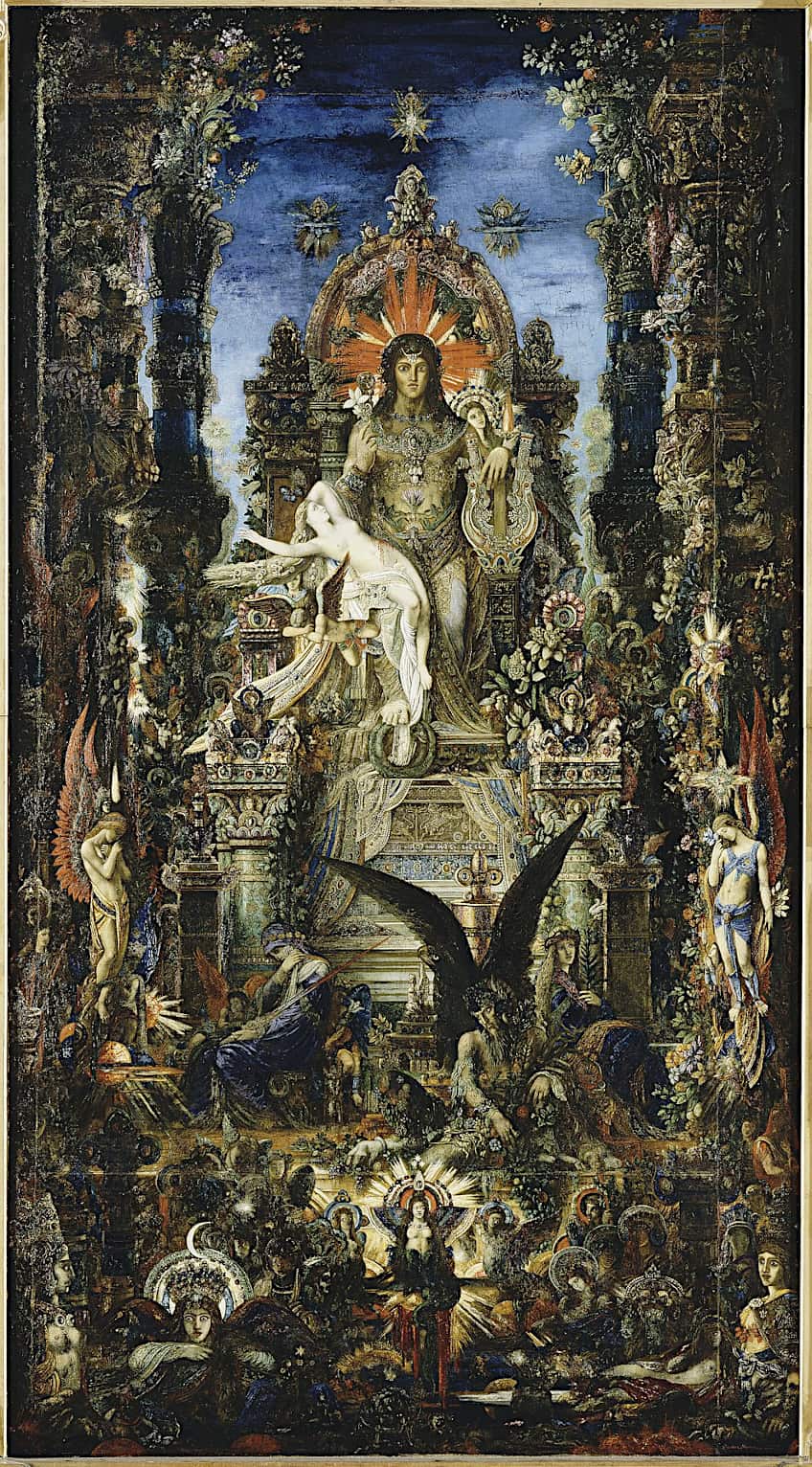

| Symbolism | 1880 – 1910 | Symbolism used symbols in their artworks to express ideas and emotion, whether through imagery, colors, lines, or text. |

| Post-Impressionism | 1885 – 1914 | This movement rebelled against impressionism to create art that was more personal and that expressed their individual styles while still being an extension of it. |

| Fauvism | 1905 – 1910 | The Fauvist style of painting is characterized by using pure color applied in an expressive manner. |

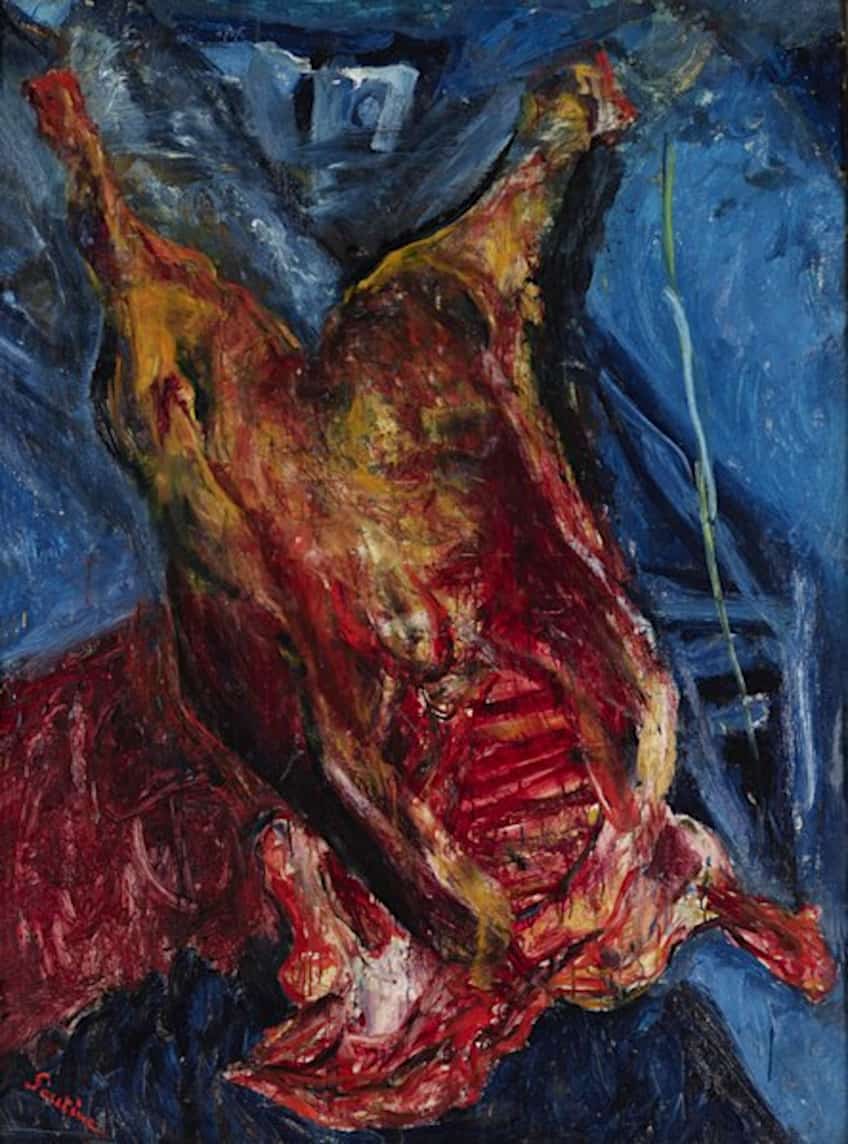

| Expressionism | 1905 – 1933 | Artists depicted their emotional reality rather than the physical world. Their style is characterized by hard lines, exaggerated expressive brushstrokes, distorted forms, and striking combinations of color |

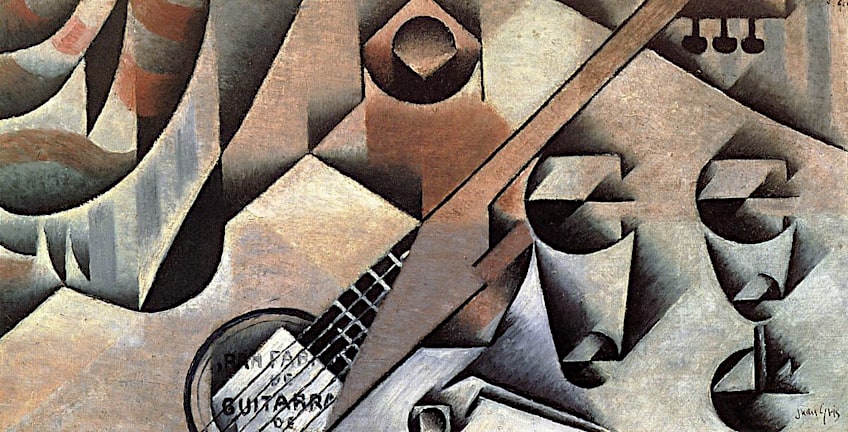

| Cubism | 1907 – 1922 | Cubism is characterized by the fracturing of objects or subjects into geometric forms, creating new points of perspective within a picture. |

| Futurism | 1909 – 1944 | Traditional ideas of art were replaced with an artistic vision that celebrated the age of technological and mechanical advancement. |

| Dada | 1916 – 1924 | Dada emphasized meaning over aesthetically pleasing artworks, often asking the viewer difficult questions about society and the world. The movement is well known for its readymades. |

| Surrealism | 1924 – 1966 | Surrealist artists were fascinated by the unconscious mind, blending fantasy and dreamlike imagery to create illogical scenes filled with symbolism. |

| Abstract Expressionism | 1943 – 1965 | The movement is characterized by personal expression and spontaneity, producing works that contain levels of abstraction, often with unrealistic forms, energetic brushstrokes, and mark-making |

| African Modernism | 20th Century | African Modernists created works using non-traditional media and subject matter and were influenced by modern movements, developing their own interpretation of modernist principles while staying true to their individual styles |

Post-Modern Movements

| Art Periods and Movements | Dates | Characteristics |

| Pop Art | 1950 – 1970 | Pop art challenged traditional fine art by introducing imagery from popular culture and media using bright colors, humor, satire, mixed media, collage, and printmaking. |

| Minimalism | 1960s – 1970s | Minimalism can be understood as an extended form of abstract art, characterized by geometric shapes and block colors |

| Conceptual Art | 1960s – 1970s | Conceptual art emphasizes meaning over aesthetically pleasing artworks, often asking the viewer difficult questions about society and the world through works that do not look like traditional art pieces. |

| Photorealism | 1960s – Present | Hyper-realistic art is created using photography rather than direct observation. |

| Feminism | 1960s – Present | Artworks were made from a woman’s perspective and often invited the viewer to ask questions regarding their social and political background and therefore, bring change to equality and rid of embedded stereotypes. |

| Neo-Expressionism | 1970s – 1990s | Neo-Expressionism brought a resurgence of painting in an expressionist way. |

| Contemporary Art | 1970 – Present | Contemporary art refers to all art made in the present time. Combining past styles and ideas, as well as advanced technologies, producing art pieces that are diverse in media and culture. |

An Overview of Art Periods and Movements

Now that we have explored the art history timeline, we can dive deeper into the various art periods and movements in more detail, starting with the earliest known evidence of art made by humans and ending with contemporary art.

Prehistoric Art (40,000 – 4,000 BC)

The term, “prehistoric” refers to a time before written records. Therefore, prehistoric art refers to any visual art that was made before the start of written history and its timeline begins with the oldest evidence of art made by humans. It is important to note that there is evidence of art that is made by people who live in parts of the world today that do not have a writing system, but for the purpose of putting together a historical timeline, we will be using the traditional eras of human prehistory. The dates used to classify the periods below are approximations as art eras reached different parts of the world at different times across several thousand years.

The Paleolithic Era (2.5 Million – 12,000 Years Ago)

The Paleolithic era or the old stone age was the longest period of human history. The earliest evidence of human use of tools is from this era, dating to 2.5 million years ago when humans made simple stone-cutting tools by flaking rocks. The use of these tools came before the making of art, but scientists are not sure how long this was.

The two kinds of art that were produced in the Paleolithic era were portable and stationary. Portable art consisted of decorated objects or figurines that were small so that they could be portable. These were figurative works that were either animal or human in shape and appearance.

The only surviving art available to study are cave paintings and engravings, that were, except for the depiction of animals, more often non-figurative, meaning that they may have served largely symbolic functions that some recent studies have suggested include tracking the breeding seasons of the various species of animals people hunted.

While there is no means of determining their purpose with certainty, scholars have suggested that Paleolithic art appears to refer mainly to food and survival, as seen in animal carvings and depicted hunting scenes, as well as fertility, which can be seen in the depiction of females of child-bearing figures. Experts speculate that stationary works may have served ritualistic or magical purposes.

| Paleolithic Artworks | |||

| Examples | Artist | Date | Location Discovered |

| Hand stencils and hand painting | Unknown | 39,000 BCE | Spanish Cantabrian cave of El Castillo, Spain |

| Rock engravings | Unknown | 37,000 BCE | Gorham’s Cave, Gibraltar, South coast of Spain |

| Venus of Willendorf | Unknown | 25,000 BCE | Willendorf, Austria |

| Venus of Laussel relief sculpture | Unknown | 23,000 BCE | In the commune of Marquay, Dordogne region of southwestern France |

| Rouffignac Cave murals | Unknown | 14,000 BCE | Alongside the La Binche river, Rouffignac-Saint-Cernin, Dordogne, France |

Mesolithic Era (12,000 Years Ago – 10,000 Years Ago)

The Mesolithic era or middle stone age was a period of transition from the oldest period of human history (Paleolithic) to the rise of civilizations and farming during the Neolithic period. People during this time were semi-nomadic and thus their lives were not only centered on hunting and foraging for survival. They started experimenting with growing their own crops which allowed them more time to create art since they did not have to spend as much time foraging.

The Mesolithic period was also a time of the Holocene, the end of the Ice Age, which ushered in a warmer climate, and meant that cave art was largely taken over by rock art created outside in the open air.

What may be considered the most significant archaeological discovery of the Mesolithic era were megalithic temples and art, especially the temple complex of Gobekli Tepe in Southeastern Turkey dating to about 9,500 BCE. This shows the capability of hunter-gatherer societies to construct such a complex, although it is still unclear how they managed it exactly.

| Mesolithic Artworks | |||

| Examples | Artist | Date | Location Discovered |

| Cave rock engravings | Unknown | 8,200 BCE | Wonderwerk Cave in the Northern Cape Province, South Africa |

| Anthropomorphic figurine | Unknown | 8th and 9th millennium BCE | Nevalı Çori in Şanlıurfa Province, Southeastern Anatolia, Turkey |

| Megalithic art | Unknown | 9,500 BCE | Gobekli Tepe near Sanliurfa in Southeastern Turkey |

| Ceramic pottery | Unknown | 11th millennium BCE | Xianrendong in Jiangxi province, China |

Neolithic Era (10,000 – 4,500 Years Ago)

The Neolithic era or the new stone age was a period in prehistory when people had taken up farming and animal husbandry in place of the semi-nomadic lifestyle of hunting and gathering food. This period is regarded as the dawn of civilization and therefore, the art created by these societies became more varied and included pottery (considered an artifact indicative of this particular period, although some Chinese and Japanese pottery predate the Neolithic), terracotta sculpture, hand stencils, engravings, adornments, sculpted statuettes, as well as megalithic art, and religious temples.

Agriculture took place at different times in various parts of the world; thus, there is no definitive date for the start of the Neolithic era. Agriculture contributed to the increase in population, and people became more protective over their territory and created large settlements, which in turn prompted them to become more organized and develop a hierarchical system.

All these social developments, including the increased belief in supernatural deities, impacted the art of the Neolithic.

| Neolithic Artworks | |||

| Examples | Artist | Date | Location Discovered |

| Xianrendong Cave pottery | Unknown | 18,000 BCE | Siberian border, Far East of Russia |

| Vela Spila pottery | Unknown | 15,500 BCE | Korcula Island, Croatia |

| Pig Dragon pendant of the Hongshan Culture | Unknown | 3,800 BCE | China |

| Stonehenge Stone Circle | Unknown | 2,600 BCE | Salisbury Plain, Wiltshire, England |

Asian Art (38,000 BCE – Present)

Asia is a vast continent with a vast history and its people have produced many types of art that precede art in the West. Asian art encompasses art from China, India, Indonesia, Japan, Korea, and the Russian Far East, and therefore would need an entire article dedicated to each.

First, ancient pottery appeared in China, as well as large bronze sculptures, Jade carvings, lacquerware, calligraphy, and sericulture. Terracotta sculpture, painting, and metalwork are outstanding contributions made by Chinese artists and Chinese culture has had a great influence on East Asian countries, such as Japan and Korea. The Japanese are renowned for their woodcuts and wood carving, ceramics, origami, and ink-wash painting.

On the Indian subcontinent, art formed more independently from China, however, it was influenced during the Hellenistic era by Greek sculpture, and Islamic art. South-East Asia is known for its Buddhist sculpture, Khmer temple architecture, some types of metallurgy, and batik textiles.

With the exception of certain types of metalwork and stone, unfortunately, much of South-East Asian art has disintegrated because of the climate.

| Asian Artworks | ||||

| Artwork | Artist | Medium | Date | Location Discovered |

| Venus of Kostenki | Unknown | Ivory | 30,000 BCE | Russia |

| Bronze Head with Gold Foil Mask | Unknown | Bronze and gold | 1,100 BCE | Sanxingdui, Sichuan, China |

| Terracotta Army | Qin Shi Huang (259-210 BCE) | Terracotta | 246 – 208 BCE | Xian, China |

| Ajanta Cave Paintings | Unknown | Tempera | 501 – 600 CE | Maharashtra, Western India |

| Pensive Bodhisattva | Unknown | Bronze | 600 – 650 CE | Korea |

| The Great Wave off Kanagawa | Hokusai (1760-1849) | Woodblock print | 1831 | Japan |

Traditional African Art (23,000 BCE – Present)

African art is diverse as there are many different cultures and lineages that covered and still do cover the continent. African art dates to pre-historic times, as far as 70,000 BCE, but for this section, we will focus on traditional African art. The word “traditional” is used here to distinguish between art created with a traditional intention within the context of historical African culture and later African art that is more modern.

African art incorporates many different mediums, objects, and themes to create striking and unique works that have influenced Western movements, such as Cubism.

Traditional African art is well known for the spectacular masks made by many cultures, which often had a ritual or religious function. Despite the differences geographically, many types African art share certain common characteristics, such as the use of sculptures made to be used during ceremonies as vessels for communicating with ancestors. Pottery is also an important art form in many African cultures, with vessels and jugs not only having a useful function but possessing beauty with detail.

Traditional African art often favors symbolism, expressionism, and abstraction over naturalistic depictions and regularly incorporates the human figure in sculpture and images.

| Traditional African Artworks | ||||

| Artwork | Medium | Date | Location Discovered | Culture |

| Rock painting | Pigments on rock | 3,000 – 2,000 BCE | Manda Guéli Cave, Chad, Central Africa | Sahara |

| Queen Mother Pendant Mask: Iyoba | Ivory, iron, copper | 16th century | Benin City, Nigeria | Benin |

| Zamble Helmet Crest Mask | Wood, pigment | 19th century | Ivory Coast, West Africa | Guro |

| Community Power Figure: Male (Nkisi) | Wood, copper, brass, iron, fiber, snakeskin, leather, fur, feathers, mud, resin | 19th – 20th century | Democratic Republic of the Congo | Songye |

| Tutu painting by Ben Enwonwu (1917 – 1994) | Oil on canvas | 1974 | Nigeria | Influenced by Yoruba and other regional styles |

Ancient Near East (3,500 – 636 BCE)

The Ancient Near East stretched from Turkey in the north, down the Mediterranean coast, and east into Iran and Mesopotamia, to the Indus River valley, covering more than three million square miles. The landscape of the region was diverse, with nomads and settled civilizations, deserts, river valleys, violence, and innovations. And therefore, the art was just as varied.

Most of the art of the Ancient Near East was religious and emphasized the relationship between the human and the divine. It was mainly used to honor the gods and goddesses or to be used in rituals. However, art was also political, and it was used by rulers to assert their power and status. The following are the five major periods of the Ancient Near East named after the groups that made them.

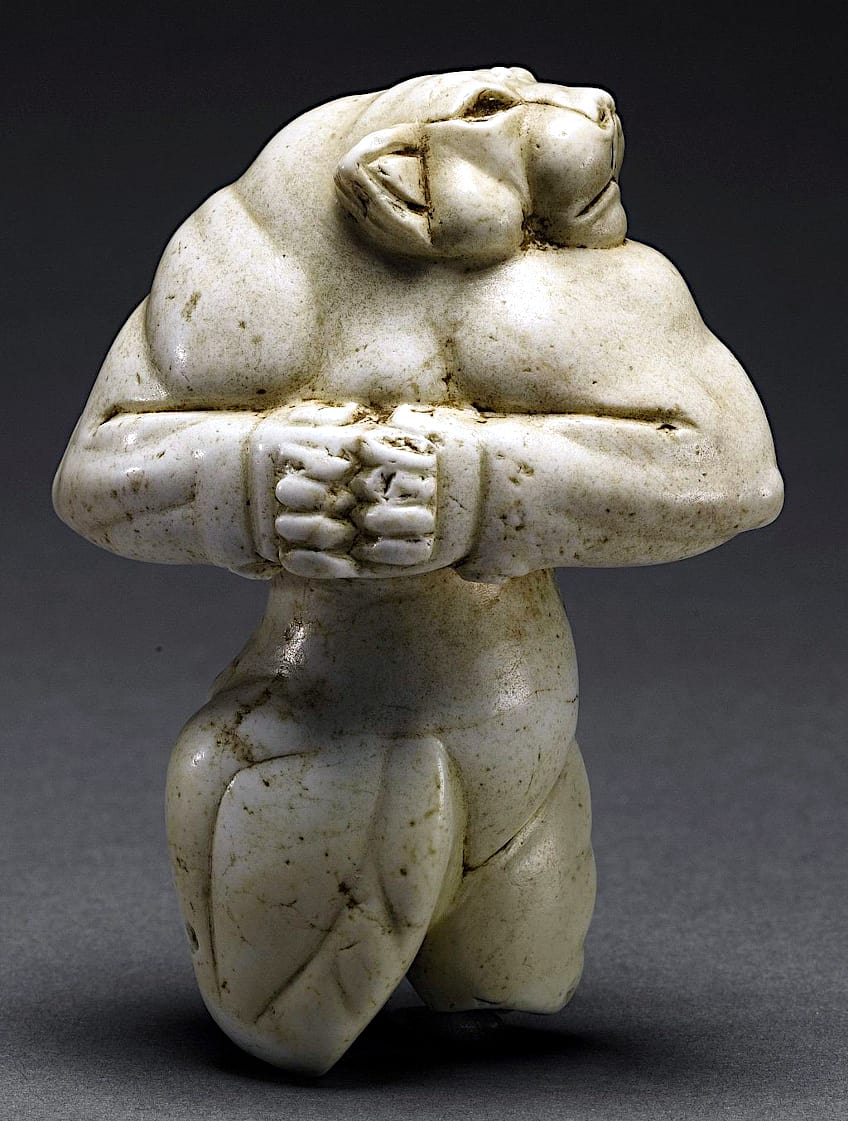

Sumerian Art (4,500 – 1,900 BCE)

The Sumerians came before the Akkadians and lived in ancient Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq) from at least 3,000 to 2,000 BCE, emptying the marshes for agriculture and establishing trade, becoming the first people to live in complex societies in that area. Their life was more settled, and they had a steady food supply which allowed for a surge in population.

Sumerian art provided the foundation for the rest of the art of the Ancient Near East. One of the first known scripts in the world, cuneiform was created by the Sumerians and was included in much of their art.

They invented new types of pottery and the stratification of their society into farmers, traders and craftsmen meant that specialized crafts like leatherwork, metalwork, and weaving, flourished. Similarly stonemasons and sculptors began creating ever larger free-standing sculptures and bronze statuettes. Evidence dating to the Third Millennium has been found of advanced techniques in bronze and copper casting.

| Sumerian Artworks | ||||

| Artwork | Artist | Medium | Date | Location Discovered |

| Warka (Uruk) Vase | Unknown | Alabaster | 3,200 – 3,000 BCE | Temple complex of the goddess, Inanna, City of Uruk, Mesopotamia |

| The Guennol Lioness | Unknown | Limestone | 3,000 BCE | Near Baghdad, Mesopotamia |

| Ram in a Thicket | Unknown | Gold, copper, lapis lazuli, limestone, and shell | 2,650 – 2,550 BCE | Ur, Southern Mesopotamia |

| The Queen’s Lyre | Unknown | Gold, mother-of-pearl, limestone, and lapis lazuli. | 2,600 BCE | The Royal Cemetery, Ur, Southern Mesopotamia |

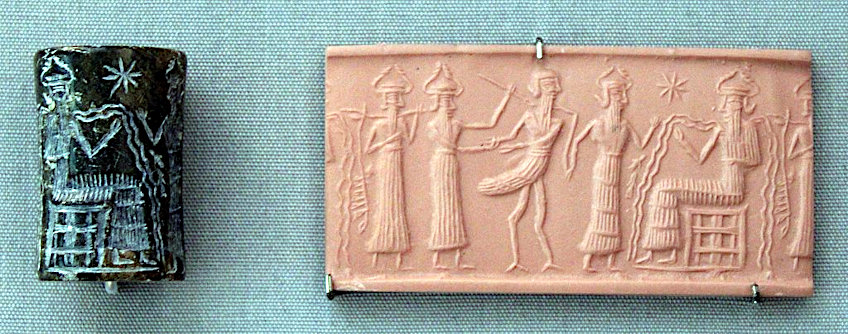

Akkadian Art (2,334 – 2,154 BCE)

The Akkadians were the successors of the Sumerians, overrunning them at around 2,270 BCE. Their leader, Sargon (reigned 2334-2279 BCE) joined the city-states of Sumer and created the first Mesopotamian empire, and thus their art focused on strengthening and declaring their power as conquerors. This was the beginning of the concept of kingship and the engendered loyalty to Sargon and those in power is reflected in the art of the time.

Akkadian art emphasized a greater degree of naturalism and complex visual narratives, as seen in bronzes, cylinder seals, and stone carvings that are more realistically rendered compared to the art of the Sumerians.

Cylinder seals were cylinder-shaped objects with engraved images that could be rolled on objects made of clay to leave an impression, serving as a signature that would identify the authority of the person responsible for the documents. A work considered to be a masterpiece of Akkadian art is the Bronze Head of a King (2,300 BCE), which is a piece of figurative sculpture that may have been of the king, Sargon.

| Akkadian Artworks | ||||

| Artwork | Artist | Medium | Date | Location Discovered |

| Bronze head of a king | Unknown | Bronze | 2,300 BCE | Nineveh, Upper Mesopotamia |

| Cylinder Seal | Unknown | Chert rock | 2250 – 2150 BCE | Mesopotamia |

| Victory Stele of Naram-Sin | Unknown | Limestone | 2254 – 2218 BCE | Sippar, southwest of present-day Baghdad |

Babylonian Art (1,895 – 539 BCE)

The Babylonians lived in Southeastern Mesopotamia between the Euphrates and Tigris rivers. Akkadians and Ammonites arrived in Mesopotamia after 1,900 BCE and obtained control of the area, building an empire with Babylon as its main city. According to existing historical records, the city had many palaces and temples that were gloriously decorated. The king, Hammurabi reigned over Babylon and subjugated most of Mesopotamia and was one of the most powerful Babylonian leaders.

Hammurabi is an important name in Babylonian art because he is famous for creating The Code of Hammurabi (1792-1750 BCE), a set of 282 laws and punishments, the most complete and earliest legal code that later influenced the laws of the entire world. The saying, “an eye for an eye” might be familiar to you. These laws were inscribed onto a stele, which is a column built for ceremonial or memorial purposes, and this stele combined law, art, and literature. A relief sculpture at the top of the stele depicts the king receiving the laws from Shamash, a highly important god.

The Babylonian art style started with clay, as it was widely available in that region of the Middle East. The Babylonians created fine pottery and built structures, such as earthen temples. Eventually, artists started using diorite stone, obtained through trade, to create sculptures that honored their leaders and gods. The next and most significant artistic style in Babylonian art included the use of multi-colored, glazed brick walls that depicted imagery of animals and deities. These images can be seen at the Ishtar Gate which was part of a huge walled processional way that led into the inner city of Babylon.

| Babylonian Artworks | ||||

| Artwork | Artist | Medium | Date | Location Discovered |

| The Burney Relief or “Queen of the Night” Relief | Unknown | Terracotta plaque | 1,800 – 1,750 BCE | Babylonia (find-site unknown), Mesopotamia |

| The Code of Hammurabi | Unknown | Black stone stele | 1792 – 1750 BCE | Susa, lower Zagros Mountains, Iran |

| The Ishtar Gate | Unknown | Glazed ceramic bricks | 604 – 562 BCE | Ishtar Gate, Babylon, Mesopotamia |

Assyrian Art (1,365 – 600 BCE)

The Assyrians dominated Northern Mesopotamia at the time of Hammurabi’s passing. During the 15th century BCE, they became an independent entity after being dependent on the Hatti and Mitanni kingdoms. Assyria eventually gained a dominant role over Mesopotamia, and by the eighth century BCE, most of the Middle East was united under their Empire. The culture of the Assyrians was one based on war and most of the empire was under the control of the military. The expansive empire had access to iron and stone, the first of which was very popular and contributed to the building of huge palaces.

Assyrian art included narrative relief sculpture rendered with detail in alabaster and stone that depicted military activities and hunting events with animals being more detailed compared to the rigid human forms. The aim of these images that greeted visitors to the palace was to glorify the power of the Assyrian kings.

Apart from the enormous anthropomorphic figures and animals that stood at royal gateways or other entrances, very few statues were made by Assyrian sculptors. A variety of ancient pottery has been discovered, as well as some jewelry art and goldsmithing. The dawn of imperialism and expansion came in 885 BCE for the Assyrians, and art created during this time was devoted to wars, hunting scenes, and conqueror-kings with each campaign meticulously recorded by scribes and artists of the court.

| Assyrian Artworks | ||||

| Artwork | Artist | Medium | Date | Location Discovered |

| Human-headed Winged Bull and Lion (lamassu) | Unknown | Gypsum | 883 – 859 BCE | The Gate of Ashurnasirpal’s palace at Nimrud, Tigris River, Mesopotamia |

| Sacking of Susa by Ashurbanipal | Unknown | Gypsum wall panel relief | 647 BCE | North Palace, Nineveh, Upper Mesopotamia |

| Ashurbanipal Hunting Lions | Unknown | Gypsum wall relief | 645 – 635 BCE | North Palace, Nineveh, Upper Mesopotamia |

Persian Empire Art (550 BCE – 330 BCE)

One of the oldest consistently inhabited regions in the world, Persia was home to one of the earliest civilizations in the history of art. It occupied the Persian plateau, surrounded by the Baluchistan and Elburz mountains in the east and north, and during the first Millennium BCE, Persian rule expanded into Central Asia and through Asia Minor, extending as far as Greece and Egypt. The Persian or Achaemenid Empire began with Cyrus the Great in 550 BCE and continued until Alexander the Great conquered it in 330 BCE. Although militaristic, the Persians allowed the people they conquered to live their lives and practice any religion they chose in exchange for taxes and tribute to the king.

A vast network of roads with strategically located resting places allowed for communication across this massive empire via equestrian messengers at a previously unimaginable speed.

Because Persia brought together people of different cultures, languages, and sociopolitical organizations, it was influenced by Greek, Sumerian, and other Mesopotamian art, and Chinese art. Early Persian art featured a variety of artistic influences and styles in small bronze works and intricate ceramics taken from neighboring and conquered lands. Other artworks of ancient Persia included painting, goldsmithing, architecture, and sculpture.

The wall reliefs that decorated the ancient city of Persepolis, for example, were symbolic and realistic, but also stylized images representing the procession of people bringing tribute to the king. Even though Persian art was heavily influenced by other cultures, it was still rendered in a distinctively Persian style.

| Persian Artworks | ||||

| Artwork | Artist | Medium | Date | Location Discovered |

| Gold Chariot from the Oxus Treasure | Unknown | Gold | 600 – 400 BCE | Takht-i Kuwad, Tadjikistan |

| Archers frieze | Unknown | Glazed siliceous bricks | 510 BCE | King Darius’ palace at Susa |

| The Gate of All Nations (Gate of Xerxes) | Unknown | Stone | 486 – 465 BCE | The ancient city of Persepolis, Iran |

| Central reliefs of the northern stairs | Unknown | Stone | 486 – 465 BCE | Apadana in Persepolis, Iran |

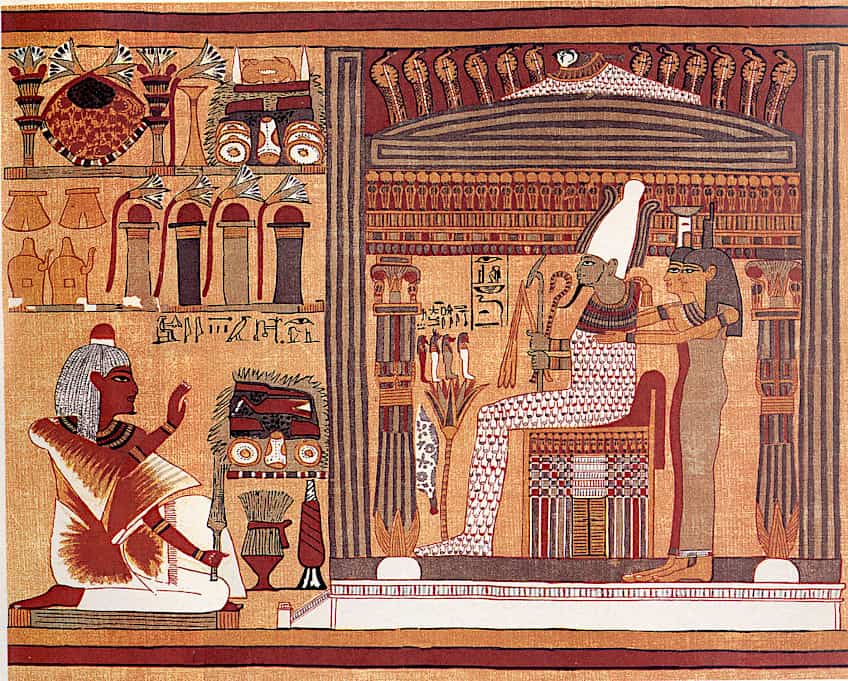

Egyptian Art (3,100 – 332 BCE)

Before Greek civilization, Egyptian art may be the most well-known ancient art form in the Mediterranean basin. Egypt was sustained by the Nile River and surrounded by borders of desert that protected it. Therefore, for many centuries Egyptian arts and crafts grew largely without disturbance or hindrance. Egyptian art was used to glorify and honor the gods (and the Pharaoh who was worshiped as a divine ruler) and to guide and assist the human journey into the afterlife.

Statues served various purposes. Some served a political purpose and were made to provide the Pharaoh with a physical presence across the two kingdoms. Images of gods allowed the deity to inhabit their temple and to travel during ritual processions. Other statues were made to aid a divine recipient or someone that had died, such as the ka statue, which was intended to provide a resting place for the spirit or ka of a person after death.

Egyptian sculpture, monuments, paintings, and crafts were created predominantly during the dynastic periods of the first 3,000 years BCE. Egyptian art was tied heavily to their religion and mythology and was often found in tombs because of their fixation with the afterlife, as well as in temples. Important characteristics of Egyptian art were the composite view of the figures, the use of geometric shapes and simplicity, as well as idealism and symbolism.

The artistic style of the Egyptians changed very little, apart from becoming more naturalistic, as this formed part of their belief in timelessness and perfection. However, there was a short period of about 17 years when the style changed to be softer, distorted, and less idealistic by the order of Akhenaten during the New Kingdom (1,570-1,544 BCE). This style is known as the Amarna style and was related to Akhenaten’s religious reforms, but it was discarded after his reign and the old religion and art style was restored.

| Egyptian Artworks | ||||

| Artwork | Artist | Medium | Date | Location Discovered |

| The Narmer Palette | Unknown | Siltstone | 3,000 – 2,925 BCE | Temple of Horus at Nekhen, Egypt |

| Khafre Enthroned | Unknown | Anorthosite gneiss | 2,570 BCE | Khafre’s Valley Temple, in the Pyramids of Giza Complex, Egypt |

| Great Sphinx of Giza | Khafre (4th dynasty) | Limestone | 2,558 – 2,532 BCE | Giza, Egypt |

| Colossal Statue of Akhenaten | Unknown | Sandstone | 1,351 – 1,334 BCE | Temple of Aten, Eastern Karnak, Thebes |

| Papyrus of Ani | Unknown | Papyrus | 1,250 BCE | Tomb of Ani, Luxor, Egypt |

Ancient Proto-Greek Art: Bonze Age Aegean Art (3,000 – 1,200 BCE)

The Bronze Age of Greece is categorized into three groups, the Cyclades, the Minoan, and Mycenaean civilizations that lived in different geographical areas of the Aegean. Each group had its own culture and their development overlapped. Below we will discuss these three categories and the art associated with them below.

Cycladic Art (3,200 – 1,050 BCE)

In the Southwestern Aegean lie a group of islands and smaller islands known as the Cyclades. Called kyklades by the ancient Greeks, these islands were understood to form a circle around the holy Island of Delos.

The Cycladic islands are rich in minerals such as copper, gold, silver, iron, lead, obsidian, emery, and fine marble. Neolithic settlements on the islands produced significant sculptures in marble stone.

By the Early Bronze Age, a civilization had emerged such as on important island sites like Halandriani on Syros and on Keros. The Cyclades became part of a favorable route for peoples traveling across the Aegean and they exported their rich mineral resources.

Cycladic culture had two main phases or periods: The Grotta-Pelos culture (3,200-2,700 BCE), and the Keros-Syros culture (2,700-2,400/2,300 BCE), and most of the marble sculptures and containers produced were made during these two periods. The Cyclades are best known for their marble sculptures with a distinctive stylized style. Most sculptures produced during the Early Cycladic phase consists of mostly female figures with some being made with natural proportions and some with idealized forms.

| Cycladic Artworks | ||||

| Artwork | Artist | Medium | Date | Location Discovered |

| Marble female figure | Unknown | Marble sculpture | 4,500 – 4,000 BCE | The Cyclades |

| Marble seated harp player | Unknown | Marble sculpture | 2,800 – 2,700 BCE | Naxos Island |

| Terracotta kernos (vase for multiple offerings) | Unknown | Terracotta | 2,300 – 2,200 BCE. | Melos Island |

| Terracotta jar | Unknown | Terracotta | 2,300 – 1,900 BCE | Melos Island |

Minoan Art (2,700 – 1,100 BCE)

One of the earliest Greek groups was the Minoan civilization that lived on an Island in the Mediterranean Sea called Crete from about 3,300 BCE. The Minoans traded goods with the surrounding regions and their pottery became quite popular. Many frescoes adorned the walls of Minoan homes, palaces, and other buildings. Unfortunately, much of the art produced during this period has deteriorated or has been destroyed, with most of the existing pieces in museums being fragments, but there are some whole artifacts that have survived, such as vases, murals, and figurines.

Minoan art depicted the everyday life of common people and their physical environment, as well as gods, goddesses, and rituals. Images of the bull were regularly used in artworks to symbolize fertility and strength.

Minoan art was unusual in that symmetry was less commonly used than in the art of neighboring peoples, while a more fluid curvilinear style informed by natural forms executed in bright colors predominated. When this art was first excavated, audiences were quick to comment on its apparent ‘modernity’.

| Minoan Artworks | ||||

| Artwork | Artist | Medium | Date | Location Discovered |

| Faience figurine of the Minoan Snake Goddess | Unknown | Faience | 1,650 – 1,550 BCE | The main sanctuary of the Palace of Knossos, Crete. |

| Procession Fresco | Unknown | Fresco | 1,600 – 1,450 BCE | Knossos, Crete |

| Minoan Bull’s Head Rhyton | Unknown | Black steatite sculpture | 1,550 – 1,500 BCE | Small palace, Knossos, Crete |

| Octopus vase | Unknown | Pottery | 1,500 BCE | Palaikastro, Crete |

Mycenaean Art (1,600 – 1,100 BCE)

The Mycenaean civilization flourished in mainland Greece during the last phase of the Bronze Age and adapted the artistic traditions of the Minoans. They made jewelry, goldwork, frescoes, pottery, and sculpture.

The Mycenaeans were influenced by the Minoan artistic style, such as their fluid design and natural shapes. However, their style was not as natural as the Minoans but was more stylized and they made use of geometric and abstract forms.

The Mycenaean warrior culture is represented in their art through depicted scenes of war, hunting, and wildlife. They traded with other peoples in the Mediterranean and imported ivory, gold, copper, as well as glass, while the Mycenaeans exported pottery and other goods to places like Mesopotamia, Egypt, Sicily, Cyprus, the Levant, and Anatolia.

| Mycenaean Artworks | ||||

| Artwork | Artist | Medium | Date | Location Discovered |

| Mycenaean Octopus Brooch | Unknown | Gold | 2,000 – 1,001 BCE | Mycenae, Greece |

| Mycenaean jug | Unknown | Pottery | 1,500 – 1,450 BCE | Kalkani tomb, Mycenae |

| Vapheio Cup | Unknown | Gold | 1,500 – 1,401 BCE | Vapheio tholos tomb, Lakonia |

| House of the Warrior Vase | Unknown | Pottery | 1,200 – 1,101 BCE | The acropolis of Mycenae |

Pre-Columbian Art (1,200 BCE – 1,535 CE)

Pre-Columbian art refers to the art of America and its islands that was created before the arrival of Columbus. The period focuses mainly on the art of Central America, Mesoamerica, and South America.

Mesoamerica and Central America

The Olmec culture of Central America (1,200-400 BCE) sculpted massive heads from boulders, and carved animals, birds, fish, and baby figurines from Jade. They were the first people in Central America to build ceremonial complexes and pyramids.

The Maya (200-900 CE) was mostly an agricultural civilization that carved and sculpted works from wood and rock and painted murals and petroglyphs.

The Mayans are known for creating an elaborate system of three calendars that recorded time over 1,000 years in advance and formed the basis for all other Mesoamerican calendar systems. The Mayans decorated their walls with vivid and unique murals that were, if not more so, as well-executed as the Mediterranean and European art of the same time.

The Toltec (901-1,199 CE) were warring peoples and are known for their relief carvings and huge statues that stand guarding their ceremonial complexes. One of the most powerful American empires was the Aztecs (1,300-1,521). Aztec artists were very advanced and used mosaics in both architecture and ceremonial mask designs, were skilled in creating adornments and decorations from metal, and in painting brightly colored frescoes.

South America

In the Andes mountains of Peru, the Chavin Civilization (1,000-300 BCE) created works of an anthropomorphic nature, producing pottery, sculptures, carvings, and murals that depicted human bodies and animal features.

The Nazca River valley culture created polychrome ceramics that depicted human and animal figures, sometimes in an abstract style. Nazca art is also known for its lines that decorate the desert landscape, depicting mysterious subjects and bird shapes in zigzags.

The Moche (1st – 8th century CE) that lived in the northern river valleys of Peru created art that was very realistic and detailed and were known for their vessels with portraits. Subject matter ranged from animals, the natural elements, sex, and gods and goddesses.

The Andes Wari Empire (600-1,100 CE) produced a variety of quality ceramics, sculpture, and architecture, and is known for depicting the oldest deity in the Americas to be visually documented, the Staff of God. On the Peruvian Coast, the Chimu Empire (900-1,470 CE) produced gold and silver portraits, and intricate feather work headdresses that included water and air animals.

| Pre-Columbian Artworks | ||||

| Artwork | Artist | Medium | Date | Location Discovered |

| The Staff God of Tiwanaku | Unknown | Carved stone gateway | c. 200 CE | Tiwanaku, Bolivia |

| Crescent Shaped Ornament with Bat | Unknown | Hammered copper | 300 CE | Moche Culture, northern river valleys on the coast of Peru |

| Totanac Hacha | Unknown | Andesite stone | 600 – 900 CE | Veracruz, eastern Mexico |

| Olmec La Venta Monument | Unknown | Stone | 600 – 1,000 BCE | La Venta, Tabasco, Mexico |

| Aztec Calendar | Unknown | Stone | 1,502 – 1,521 CE | Mexico City |

Ancient Greek Art (900 – 27 BCE)

The ancient Greek art that we commonly think of today properly appeared between 700-800 BCE. This style was preceded by the proto-Geometric and Geometric periods. The Geometric style was in use from around 900 BCE until 700 BCE. When people think of Ancient Greek art they generally do not envision anything from this period. It was the last truly Mycenean-Greek art before the development of the now familiar styles of Greek artistry.

As the name suggests, the Geometric style consisted mainly of rhythmic abstract geometric motifs applied in closely set horizontal bands. Towards the later stage, highly stylized human and animal figures begin to appear, first as decorative elements, but later in narrative scenes.

It is important to keep in mind that apart from pottery, much of the original art from Greek Antiquity has been lost, leaving us reliant on written records and copies by Roman artists. Therefore, apart from a few exceptions like Phidias, we know quite little about individual Greek artists. Greek art is ordered into four or even five main periods, we will discuss three of these below.

Archaic Period (650 – 480 BCE)

The Archaic period in Greek Antiquity was a time of gradual experimentation. Greek pottery from the pre-archaic period involved large vases and other containers decorated in a geometric style with zigzags, triangles, and other shapes. An Oriental style can be seen in pottery from about 700 BCE as Greeks formed renewed contact with eastern parts of the world, such as the Black Sea basin, Anatolia, and the Middle East.

During the Archaic period itself, we see more figurative work with zoomorphs, animals, and gods, indicating the first signs of Greek fascination with the human form.

Black-figure-pottery was a style introduced by Corinth, depicting themes like the Labors of Hercules and the celebrations of Dionysus, and later led to red-figure-pottery dominated by the Athenians.

Greek Archaic sculpture was heavily influenced by the Egyptians and Syrians. Stone friezes, reliefs, and statues were created in stone, bronze, and terracotta, and smaller works were in bone and ivory. Daedalic style (650-600 BCE) free-standing sculptures by Daedalus, Skyllis, and Dipoinos depicted two stereotypes: kore and kouros (the draped standing girl and the nude youth), of which male nudes were considered more important.

Initially, the style of these sculptures was quite rigid and had the “frontal” style of Egyptian sculpture. As time progressed, sculptures became more realistic and less rigid with a more relaxed pose.

Most sculptures and vases were painted in bright colors and patterns. There is also evidence of fresco paintings on the walls of temples, tombs, and municipal buildings. However, few paintings have survived from the Archaic period due to vandalism, destruction, and erosion.

| Archaic Artworks | ||||

| Artwork | Artist | Medium | Date | Location Discovered |

| Two bronze helmets | Unknown | Bronze | Late 700 – 601 BCE | Afrati, Crete |

| Terracotta dinos (mixing bowl) | Unknown | Terracotta; black figure painting | 630 – 615 BCE | Corinth, Greece |

| Marble statue of a kouros (youth) | Unknown | Marble | 590 – 580 BCE | Attica, Athens, Greece |

| Terracotta amphora (jar) | Unknown | Terracotta; black-figure painting | 530 BCE | Etruria, Italy |

Classical Period (480 – 323 BCE)

The Classical period in Greek Antiquity saw Athens as being the strongest Greek city-state after defeating the Persians in 490 and 479 BCE. Their leading cultural influence would come to dominate Roman art and 2,000 years later represented the artistic standard for Renaissance art. Sculptors made great technical progress in the naturalistic depiction of the human body during this time. Subjects expanded from the usual religious subjects to broad types and specific individuals, such as politicians, athletes, philosophers, poets, etc.

The introduction of the “Canon of Proportions”, a set of mathematical ratios used to create the idealized human figure (also used by the Egyptians), contributed to the highly realistic depiction of these sculptures. Contrapposto was also invented during this period, in which the figure is standing with most of their weight on one leg, with the other knee bent; a pose most of us recognize even today.

Classical Greek painting was naturalistic in style and artists showed a good understanding of linear perspective. All types of painting thrived during this period, the highest form being panel painting according to Pliny (23-79 BCE), which depicted still-lifes, figurative scenes, and portraits. Fresco painting was done on the walls of public buildings, houses, temples, and tombs.

| Classical Greek Artworks | ||||

| Artwork | Artist | Medium | Date | Location Discovered |

| Terracotta amphora (jar) | Unknown | Terracotta | 490 BCE | Nola, Italy |

| Parthenon Frieze | Unknown | Marble | 443 – 437 BCE | The Parthenon, Greece |

| Marble grave stele with a family group | Unknown | Marble | 360 BCE | Attica, Greece |

| Great Tomb at Vergina | Unknown | Fresco painting | 326 BCE | Philip II tomb, Vergina, Greece |

Hellenistic Period (323 – 27 BCE)

The Hellenistic period began at around the same time as Alexander the Great’s death in 356 BCE and when the Persian Empire was integrated into the world of the Greeks. All the civilized world had been influenced by Hellenism (ancient Greek culture) by this time and cities such as Alexandria, Miletus, Pergamum, and Antioch had become centers of Greek arts and culture. However, the death of Alexander led to a decline in the imperial power of the Greeks and the empire was divided among three of his generals.

The Greek cultural influence remained strong. Even as the ancient Romans had taken control of the Greek empire by 27 BCE, they admired the Greeks and copied their art for hundreds of years.

Hellenistic sculpture carried on the trend of the Classical period of depicting figures with even more naturalism. Now, animals and ordinary people of any age were used as sculptural subjects and were often commissioned by wealthy people to display in their gardens and homes. The idealized beauty and serenity that had been preferred before now gave way to more emotion and realism. A market for Greek sculpture grew from the overseas Greek cultural centers that had been established and statues and reliefs were being exported to places like Egypt, Turkey, and Syria.

Like sculpture, Hellenistic painting also became popular, the favorite subject matter being contemporary events and mythology, which were succeeded by genre painting, portraits, still-lifes, animal paintings, landscapes, and other subjects.

| Hellenistic Artworks | ||||

| Artwork | Artist | Medium | Date | Location Discovered |

| Hades abducting Persephone | Unknown | Fresco painting | 340 BCE | Vergina, Macedonia, Greece |

| Winged Victory of Samothrace | Unknown | Marble | 200 – 190 BCE | Samothrace Island, north of the Aegean Sea |

| Venus de Milo | Unknown | Marble | 130 – 100 BCE | Milos, Greece |

| Alexander Mosaic | Unknown | Mosaic | 100 BCE | House of the Faun, Pompeii, Italy |

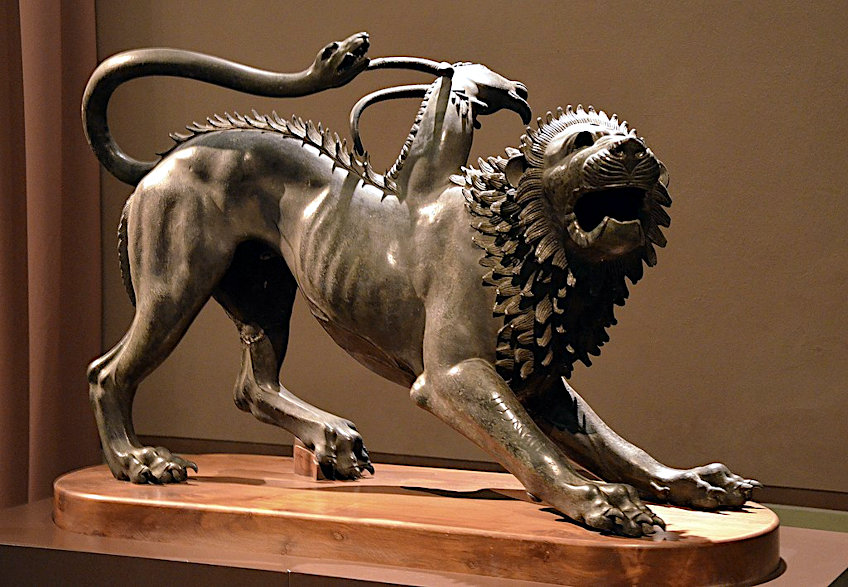

Etruscan Art (700 – 509 BCE)

The Etruscan civilization occupied central Italy between the Tiber and Arno rivers and spread as far as Campania in the south and the Po River valley in the north. They flourished until about 200 BCE when they were fully taken over by the Romans who succeeded them. The Etruscans were greatly influenced by the art of the Greeks, as Etruria imported it. The art of the Etruscans was mainly urban, funerary, and sacred. They were known for their two-dimensional style wall frescoes and realistically rendered terracotta portraits found in tombs.

Bronze sculptures and reliefs were also produced, but the Etruscans are especially known for their free-standing sculpture and reliefs in terracotta.

| Etruscan Artworks | ||||

| Artwork | Artist | Medium | Date | Location Discovered |

| Bronze statuette of a young woman | Unknown | Bronze | 600 – 501 BCE | Asciano, Italy |

| Chimera of Arezzo | Unknown | Bronze | 400 BCE | Arezzo, Tuscany, Italy |

| Etruscan Tomb of Orcus | Unknown | Fresco | 350 BCE | Tarquinia, Viterbo, Lazio, Italy |

| Sarcophagus of Seianti Hanunia Tlesnasa | Unknown | Painted terracotta | 150 – 130 BCE | Poggio Cantarello, Tuscany, Italy |

Ancient Roman Art (735 BCE – 337 CE)

The Romans established themselves in central Italy and were influenced by cultures such as the Etruscans and later by the Greeks whose art they revered, but although the Romans absorbed aspects of these and other cultures, they still retained their own character. This is especially seen in portraiture, architecture, and relief. The Roman Empire expanded rapidly from the first century BCE and this spread Graeco-Roman art and culture to North Africa, Europe, and near Asia, allowing a multitude of provincial arts to develop. The legacy and remains of Roman architecture are especially widespread.

There is an immense variety of Roman art, and this makes it difficult to classify, however, the influence that it had on Renaissance and the Neo-Classical art makes it quite familiar to us.

A significant aspect of Roman public art was the honoring of important people, as demonstrated by the outstanding portraits of the later Roman Republic. Particularly under the Roman Empire, we see reliefs depicting the triumphs of emperors decorating columns, such as Trajan’s Column (110 CE) and commemorative arches. These images served as propaganda ensuring that every citizen knew who the emperor was, and what his most important achievements and attributes were. Commemoration can also be seen in Roman coinage, depicting beautiful portraits as well as divine imagery.

Paintings lavishly decorated elite and public Roman interior space. Much of the evidence for Roman interior decoration during the first century BCE and the first century CE comes from the cities of Herculaneum and Pompeii that were destroyed when Mount Vesuvius erupted in the year 79 CE. Some of the styles show Hellenistic influence, such as the depiction of panels on colored marble, and mythological or landscape painting.

Mosaics are considered to be typically Roman, but they also came from Greece originally. Many Roman mosaics were geometric in form with different styles seen across the Empire, but subjects ranged from mythological subject matter to wild beast fights, landscapes, gladiatorial combat, and marine mosaics.

| Ancient Roman Artworks | ||||

| Artwork | Artist | Medium | Date | Location Discovered |

| Augustus from Prima Porta | Unknown | Marble | 1 – 100 CE | Villa of Livia, Italy |

| The Alexander Mosaic | Unknown | Floor mosaic | 100 BCE | The House of the Faun in Pompeii, Italy |

| Trajan’s Column | Architect Apollodorus of Damascus (2nd century CE) | Marble | 110 CE | Rome, Italy |

| Colossus of Constantine | Unknown | Marble, wood, brick, gilded bronze | 312 – 315 CE | Rome, Italy |

Early Christian Art (About the 2nd Century – 525 CE)

Paleochristian art or Early Christian art was made by Christians from the beginning of Christianity until between the years 260 and 525. It is difficult to know when Christian art truly began as Christians were a persecuted group mainly consisting of followers from the lower classes and therefore the production of long-lasting art may have been limited before 100 CE. The same creative forms were used by the Early Christians as the pagans, such as sculptures, frescoes, illuminated manuscripts, and mosaics.

Scholars generally divide Early Christian art into two periods: Before and after the legalization of Christianity in the Roman Empire in 313 by the Edict of Milan. Imperial sponsorship thereafter made the religion quite popular and wealthy, and people from various classes of society became converts. Art of the Early Christian period was grounded in the classical Roman Style but grew into a more simplified artistic style.

Physical beauty was not the focus but the spiritual, with figures no longer being depicted as individuals but as categories of people with big eyes that stared at the viewer. Symbolism was important and often used, while compositions were flat and hierarchical.

| Early Christian Artworks | ||||

| Artwork | Artist | Medium | Date | Location Discovered |

| Noah Fresco in the Catacombs of Priscilla | Unknown | Painting on plaster | 201 – 300 CE | Catacombs of Priscilla, Rome, Italy |

| Christ and the Apostles, Catacombs of Domitilla | Unknown | Wall painting | 301 – 400 CE | Rome, Italy |

| Sarcophagus of Junius Bassus | Unknown | Marble | 359 CE | Near the Confessio of the Vatican Basilica, Vatican City, Italy |

Middle Ages or Medieval Art (About 500 – 1400/1500 CE)

Medieval art includes a variety of art and architecture that was produced during the Middle Ages, beginning from about 500 to 1400–1500 CE. In Europe, early Medieval art was a mixture of the Roman artistic tradition and Northern European culture, as well as the early Christian church. Below we will discuss the various art periods that fall within the Medieval Art category.

Byzantine Art (324 CE – 1453 CE)

Byzantine art refers to various types of art created in the Byzantine Empire, especially by people in the eastern region. Most of the artistic subject matter was Christian, as the original seat of the Catholic church resided in Constantinople, the center of the Byzantine Empire. Although various types of art were produced, this period is well known for its mosaics, and iconography. The Byzantine Art period can be divided into three sections: Early (330-730), Middle (843-1204), and Late (1261-1453) Byzantine.

It can be difficult for art historians to clearly mark when Early Christian art ended, and Byzantine art began. Many of the trends in Early Christian art find full expression in Byzantine art, such as mosaics.

Few works of Byzantine art survived as the Empire experienced more than a few periods of iconoclasm during which religious images were destroyed and many mosaics were damaged or wiped out. Much of the best examples of Byzantine art can be found in the west, not in the east where the Empire was stationed because iconoclasm did not come about there, and Islam never gained control.

Some of the characteristics of Byzantine art are a two-dimensional, abstract style, Christian themes with heavy Greek influence, and the imperial use of religious propaganda (as the Byzantine Empire was initially established as a Christian empire, and the Church was ruled by the emperor).

| Byzantine Artworks | |||

| Artwork | Date | Artist | Medium |

| Mosaic of Emperor Justinian I, Basilica of San Vitale | 527 CE | Unknown | Mosaic |

| Theotokos of Vladimir (Virgin of Vladimir) | 1131 CE | Unknown | Tempera |

| Christ Pantocrator in the Hagia Sophia in Instanbul | 1261 CE | Unknown | Mosaic |

| Madonna and Child | 1300 CE | Duccio di Buoninsegna (c. 1255-1260 – c. 1318-1319) | Tempera |

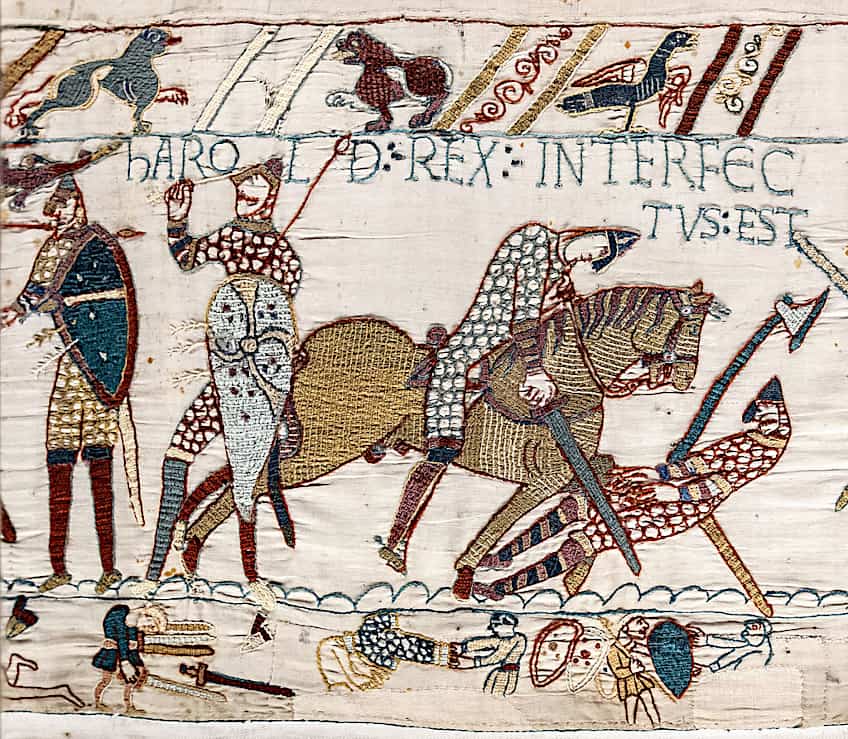

Romanesque Art (1000 – 1150 CE)

As 1000 CE drew near, many people believed that the second coming of Christ would take place at this time. However, as the millennium came and went, and the second coming did not take place, people were disappointed, and put their religious verve into the art of what is known as the Romanesque period.

Art and culture exploded across Europe as Christianity triumphed, trade routes reopened, commerce and manufacturing had been revived, cities and towns were re-established, and the middle class of merchants and craftsmen grew.

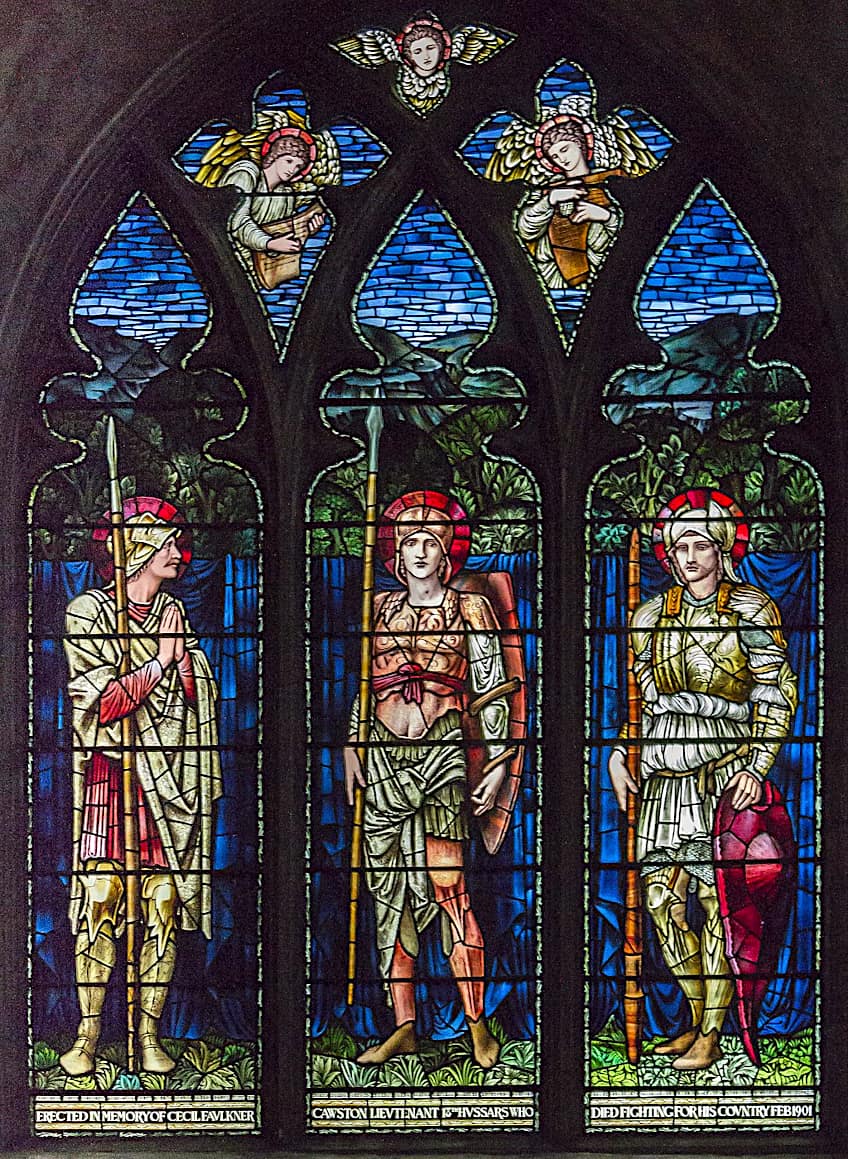

The Romanesque period was influenced by both Byzantine and Roman art styles and focused on Christian religious subject matter. Romanesque art included wall murals, stained glass works, illuminated manuscripts, sculptures, and engravings on columns and building structures. It was also during this period that sculpture re-emerged, an art form that earlier Christians had been avoiding for many years as it was considered idolatry.

Romanesque art styles were first developed in France and from there spread to other parts of Europe, such as Italy, Germany, Spain, and England.

| Romanesque Artworks | |||

| Artwork | Date | Artist | Medium |

| Bayeux Tapestry | 1070 | Unknown | Embroidered tapestry |

| Pórtico da Gloria of Santiago Cathedral | 1168 – 1211 | Master Mateo (c. 1150 – c. 1200 / c. 1217) | Sculpture |

| Judgement of Solomon at Strasbourg Cathedral | 1200 | Unknown | Stained glass |

| Madonna and Child | 1230s | Berlinghiero Berlinghieri (1175-1235) | Tempera on wood |

Gothic Period (1150 – 1375)

Gothic art started developing in the 12th century, growing from the Romanesque art period and eventually replacing it in popularity across Europe. “Gothic style” refers to sculpture and architecture (as seen in the grand Gothic cathedrals of France) in Europe that connected Romanesque art with the period of the early Renaissance.

The Gothic period is divided into three sections, Early Gothic (1150-1250), High Gothic (1250-1375), and International Gothic (1375-1450) and is characterized by the use of perspective, light and shadow, dimensions, and brighter colors that indicated a gradual shift back toward realism, a concept that had been cast out for some time. New subject matter was introduced, and experimentation took place as religion was no longer the most crucial aspect of art.

| Gothic Artworks | |||

| Artwork | Date | Artist | Medium |

| The Western (Royal) Portal of the Chartres Cathedral | 1145 | Unknown | Architectural sculptures |

| Sainte Chapelle – Stained Glass Windows | 1242 – 1248 | Unknown | Stained glass |

| The Miracle of the child falling from the balcony | 1328 | Simone Martini (1284-1344) | Tempera on panel |

| The Lady and the Unicorn: À Mon Seul Désir | 1401 – 1500 (late 15th century) | Meister der Apokalypsenrose der Sainte Chapelle ([s.a]) | Wool and silk tapestry |

The Renaissance (1400 – 1600s)

The Renaissance art period followed the Middle Ages and included works of art, architecture, and music made from the 14th to the 16th centuries, emerging in Italy and spreading to other parts of Europe. The term “renaissance” means “rebirth” and the period consisted of increased awareness and interest in nature, individualism, the resurgence of classical education, and humanism.

The Renaissance is divided into three main periods, the Early Renaissance (1401-1490s), the High Renaissance (1490s-1527), and the Late Renaissance (1520-1600) (otherwise known as Mannerism). Greatly influenced by the ideas of the ancient Greeks and Romans, the decorative art, painting, and sculpture produced during this period captured the beauty of nature and individual experience, emphasizing balance and figural proportion.

Major names from the Renaissance art period are Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519), Michelangelo (1475-1564), and Raphael (1483-1520).

| Renaissance Artworks | |||||

| Title | Artist | Date | Dimensions (cm) | Medium | Current Location |

| The Kiss of Judas | Giotto (1267 – 1337) | 1306 | 200 x 185 | Fresco | Scrovegni (Arena) Chapel, Padua, Italy |

| David | Donatello (1386 – 1466) | 1430 – 1440 | 51 x 158 | Bronze | Muse Nazionale del Bargello, Florence, Italy |

| La Primavera | Sandro Botticelli (1445 – 1510) | 1477 – 1482 | 202 x 314 | Tempera on panel | Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy |

| Pietà | Michelangelo (1475 – 1564) | 1498 – 1499 | 174 x 195 | Marble | St Peter’s Basilica, Vatican City, Italy |

| David | Michelangelo (1475-1564) | 1501 – 1504 | 517 x 199 | Marble | Galleria dell’Accademia, Florence, Italy |

| The Mona Lisa | Leonardo da Vinci (1452 – 1519) | 1503 – 1506 | 77 x 53 | Oil on poplar panel | The Louvre Museum, Paris, France |

Mannerism (1527 – 1580)

Mannerism took over as the leading style in Italy from the end of the High Renaissance and continued until the Baroque period, spreading to Northern Italy, as well as to northern and central Europe. It was a reaction to High Renaissance naturalism and classicism, focusing instead on figural composition and solving complicated artistic problems. For example, depicting the nude figure in intricate unnatural poses.

Figures often had elongated arms and legs, small hands, and other exaggerated and contrasting details that made Mannerists’ work more artificial and expressive compared to their Renaissance predecessors who were captivated by balance and proportion.

| Mannerism Artworks | |||||

| Title | Artist | Date | Dimensions (cm) | Medium | Current Location |

| Entombment | Jacopo da Pontormo (1494-1557) | 1528 | 313 x 192 | Oil on panel | Santa Felicità, Florence, Italy |

| Madonna with the Long Neck | Parmigianino (1503-1540) | 1535 – 1540 | 219 x 135 | Oil on panel | Uffizi Gallery, Italy |

| Perseus with the head of Medusa | Benvenuto Cellini (1500-1571) | 1545 – 1554 | 71.5 high | Bronze | Loggia dei Lanzi, Florence, Italy |

| Eleanor of Toledo | Bronzino (1503-1572) | 1545 | 115 x 96 | Oil on panel | Uffizi Gallery, Italy |

| The Rape of the Sabine Women | Giambologna (1529-1608) | 1583 | 410 (h) | Marble | Loggia della Signoria, Florence, Italy |

Baroque (1600 – 1750)

Deriving from the Portuguese word, barueco, which translates to “irregularly shaped pearl”, the Baroque period differed from the balance and harmony of the Renaissance and was intended to bring about emotion in the viewer and evoke awe. The Baroque period consisted of art and architecture that was over-the-top and ornate, and the artistic style was dramatic and complex.

High contrast was characteristic of Baroque art and artists painted light foregrounds with darker backgrounds, while subjects were often depicted as being in motion with torsion in the body.

Religion dominated and influenced artistic content and output at this time in history, and the Baroque themes and art styles between Northern and Southern Europe differed because of the impact of the Protestant Reformation and Catholic Counter-Reformation.

| Baroque Artworks | |||||

| Title | Artist | Date | Dimensions (cm) | Medium | Current Location |

| The Calling of St Matthew | Caravaggio (1571-1610) | 1600 | 322 x 340 | Oil on canvas | San Luigi dei Francesi, Rome, Italy |

| Judith Slaying Holofernes | Artemisia Gentileschi (1593-1653) | 1612 – 1613 | 158.8 x 125.5 | Oil on canvas | National Museum of Capodimonte in Naples, Italy |

| The Night Watch | Rembrandt (1606-1669) | 1642 | 363 x 437 | Oil on canvas | Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Netherlands |

| Ecstasy of Saint Teresa | Giovanni Lorenzo Bernini (1598-1680) | 1647 – 1652 | 350 (h) | Marble | Santa Maria della Vittoria, Rome Italy |

| Las Meninas | Diego Velázquez (1599-1660) | 1656 | 318 x 276 | Oil on canvas | Museo del Prado, Madrid, Spain |

| Girl with a Pearl Earring | Johannes Vermeer (1632-1675) | 1665 | 44.5 x 39 | Oil on canvas | Mauritshuis, The Hague, Netherlands |

Rococo (1702 – 1780)

The Rococo art style originated in Paris in the early 18th century and was embraced throughout France and later in other parts of Europe, such as Austria and Germany. Artists of the Rococo period reacted against the heaviness of the earlier Baroque style, rather creating works characterized by theatricality, lightness, and elegance, with a whimsical flair.

Design and architecture incorporated more natural curves based on the “S” and “C” shapes, and the major colors used were pastels, gold, and ivory.

Rococo comes from the French word, “rocaille”, which means rock or pebble and refers to the rock work covered in shells that decorated man-made grottoes and fountains.

Themes often featured in Rococo paintings were ones of playfulness, nature, love and romance, youth, and light-hearted entertainment painted in happy pastel colors.

| Rococo Artworks | |||||

| Title | Artist | Date | Dimensions (cm) | Medium | Current Location |

| Soap Bubbles | Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin (1699-1779) | 1733 – 1734 | 61 x 63.2 | Oil on canvas | Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, United States |

| La Toilette de Vénus | François Boucher (1703-1770) | 1751 | 108.3 x 85.1 | Oil on canvas | The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, United States |

| Portrait of Madame de Pompadour | François Boucher (1703-1770) | 1756 | 212 x 164 | Oil on canvas | Alte Pinakothek, Munich, Germany |

| The Trevi Fountain | Niccolo Salvi (1697-1751) | 1732 – 1762 | 2000 x 2600 | Sculptural architecture | Rome, Italy |

| The Swing | Jean-Honoré Fragonard (1732-1806) | 1767 | 81 x 64.2 | Oil on canvas | Wallace Collection, London, United Kingdom |

Neoclassicism (1750 – 1850)

The Neoclassical art movement (known as Neoclassicism or Classicism) was inspired by the ideas and styles of classical antiquity that came with a widespread revival of interest in ancient Greece and Rome art. The movement was initially a reaction against the lavish Rococo style and reflected the advances in areas of society during the Age of Enlightenment in the 18th century, such as science and philosophy.

Mainly, the movement aimed to impart a moralizing message to the viewer through the ideal virtues expressed in art. Neoclassicism is characterized by harmony, idealism, and restraint, while emphasis was placed on closed compositions and line rather than color.

It was an exciting time when ancient places like Pompeii and Herculaneum were being discovered in archaeology, and paintings focused on Classical themes and subject matter that were placed in archaeological settings.

| Neoclassical Artworks | |||||

| Title | Artist | Date | Dimensions (cm) | Medium | Current Location |

| Death of General Wolfe | Benjamin West (1738-1820) | 1770 | 151 x 213 | Oil on canvas | National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, Canada |

| Psyche Revived by Cupid’s Kiss | Antonio Canova (1757-1822) | 1777 | 155 x 168 | Marble | Louvre Museum, Paris, France |

| Oath of the Horatii | Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825) | 1784 | 329.8 x 424.8 | Oil on canvas | Louvre Museum, Paris, France |

| King Lear Weeping over the Dead Body of Cordelia | James Barry (1741-1806) | 1786 – 1788 | 269.2 x 367 | Oil on canvas | Tate, London, United Kingdom |

| The Death of Marat | Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825) | 1793 | 162 × 128 | Oil on canvas | Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels, Belgium |

Romanticism (1780 – 1850)

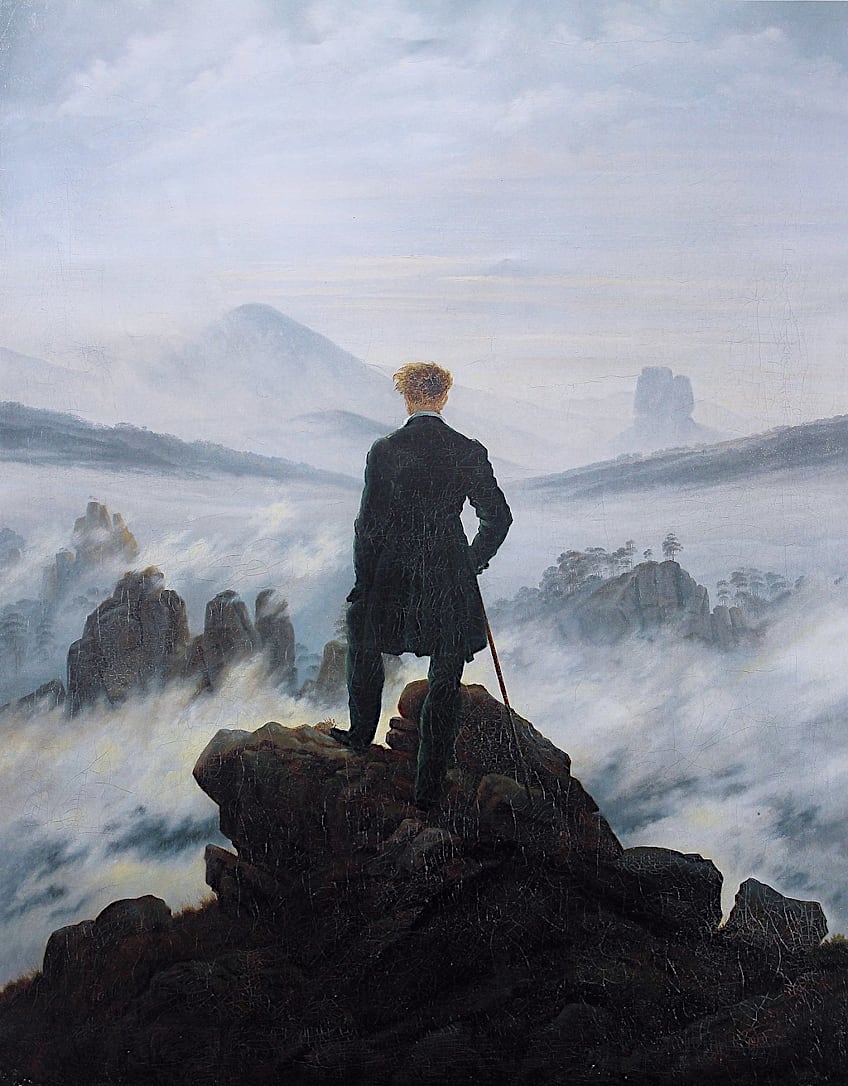

Romanticism spread through Europe and the United States from the end of the 18th century into the 19th century, challenging the ideals of order and reason held during the Enlightenment, and calling attention to the equal importance of emotions and perception. In seeking individual rights and liberty, the movement embraced the struggles for freedom and equality.

Romanticism celebrated intuition and imagination, valuing originality, and found its way not only into the visual arts but also music, literature, and architecture. Many artists of the Romantic movement began painting outdoors and turned to nature as inspiration in an effort to slow the influence of industrialization, emphasizing people as being at one with nature.

| Romantic Artworks | |||||

| Title | Artist | Date | Dimensions (cm) | Medium | Current Location |

| The Nightmare | Henry Fuseli (1741-1825) | 1781 | 101.6 x 127 | Oil on canvas | Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit, Michigan, United States |

| The Third of May 1808 | Francisco Goya (1746-1828) | 1814 | 268 x 347 | Oil on canvas | Museo del Prado, Madrid, Spain |

| Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog | Caspar David Friedrich (1774-1840) | 1818 | 94.8 x 74.8 | Oil on canvas | Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg, Germany |

| The Hay Wain | John Constable (1776-1837) | 1821 | 130.2 x 185.4 | Oil on canvas | National Gallery, London, United Kingdom |

| Liberty Leading the People | Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863) | 1830 | 260 × 325 | Oil on canvas | The Louvre Museum, Paris, France |

Realism (1848 – 1900)

Realism is generally considered as being the first modern art movement, establishing itself in France during a time of extensive social change and revolution in Europe. Realism swapped the traditional idealistic subject matter and imagery in art with events and subjects from real life painted in a naturalistic way, abandoning the pictorial and narrative techniques of the Academies. A strategy that would later influence 20th-century modernism.

The fact that Realist artists chose to depict the modern world and everyday life in their art, not conforming to and re-evaluating traditional art systems, is why the movement is seen as the first movement in modern art as it broadened the ideas of what constituted art.

| Realism Artworks | |||||

| Title | Artist | Date | Dimensions (cm) | Medium | Current Location |

| A Burial at Ornans | Gustave Courbet (1819-1877) | 1849 – 1850 | 315 x 660 | Oil on canvas | Musée d’Orsay, Paris, France |

| The Stone Breakers | Gustave Courbet (1819-1877) | 1849 – 1850 | 170 x 240 | Oil on canvas | Destroyed by a bombing during World War II in Dresden, Germany |

| The Gleaners | Jean-François Millet (1814-1875) | 1857 | 83.8 x 111.8 | Oil on canvas | Musée d’Orsay, Paris, France |

| Olympia | Édouard Manet (1832-1883) | 1863 | 130.5 x 190 | Oil on canvas | Musée d’Orsay, Paris, France |

| Song of the Lark | Jules Breton (1827-1906) | 1884 | 110.6 x 85.8 | Oil on canvas | The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, United States |

Photography

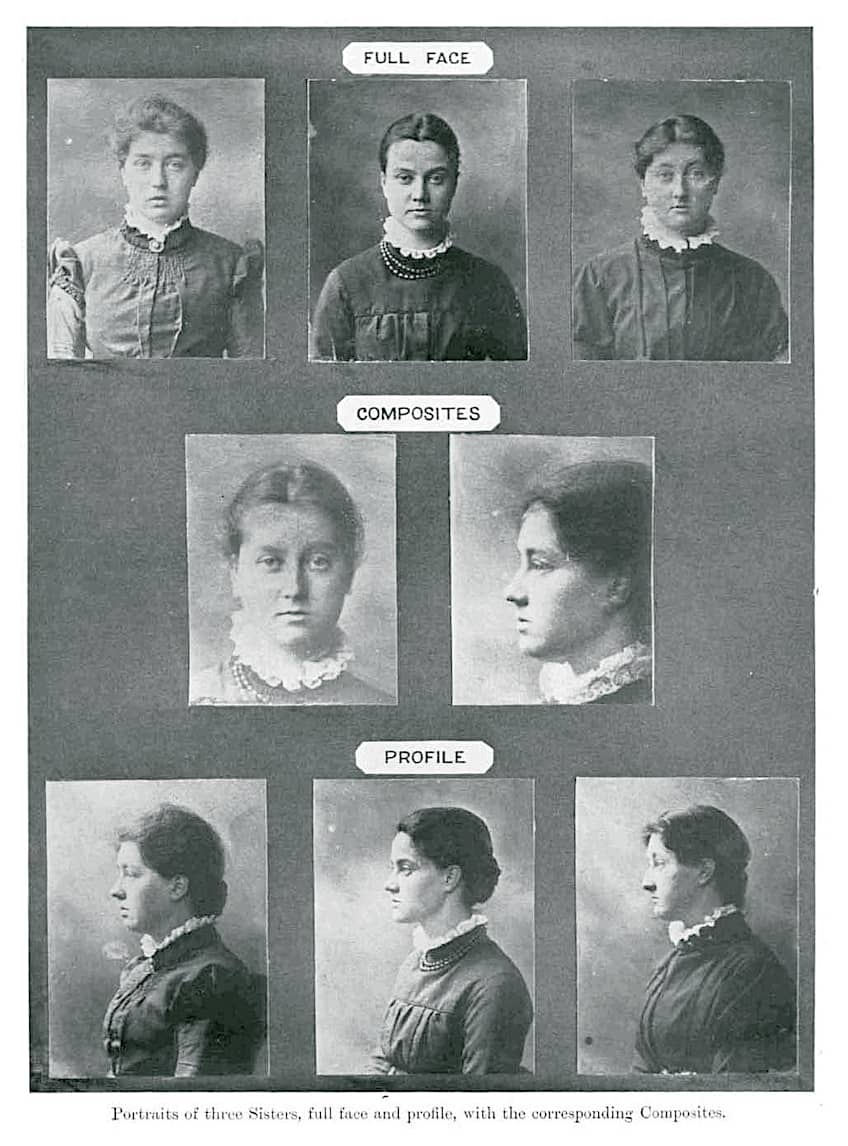

Photography is the process of recording an image of an object through the action of light (or radiation) on a surface that is light-sensitive, such as film. It is an art form that was invented in the 1930s and has become one of the most popular forms of creative expression in the world.

Early Photography (1840 – 1900)

Before photography, there was the Camera Obscura, which is believed to have been created in the 13th or 14th century. It was essentially a dark box with a hole on one side, allowing light to come through and produce an image on the surface it touches. In 1939, the first glass negative was invented by Sir John Herschel, who also came up with the term, “photography”. It comes from fos, which means “light” in Greek, and grafo, which means “to write”.

Initially, photography was used to aid artists in their work and followed the same artistic principles or was used for capturing portraits. As cameras developed and became more refined, they became available to people of the middle class.

Color photography came onto the market in 1907 after several methods were explored. The first color plate used a screen of filters that allowed light through in the colors red, green, and blue, which developed into a negative and turned into a positive later.

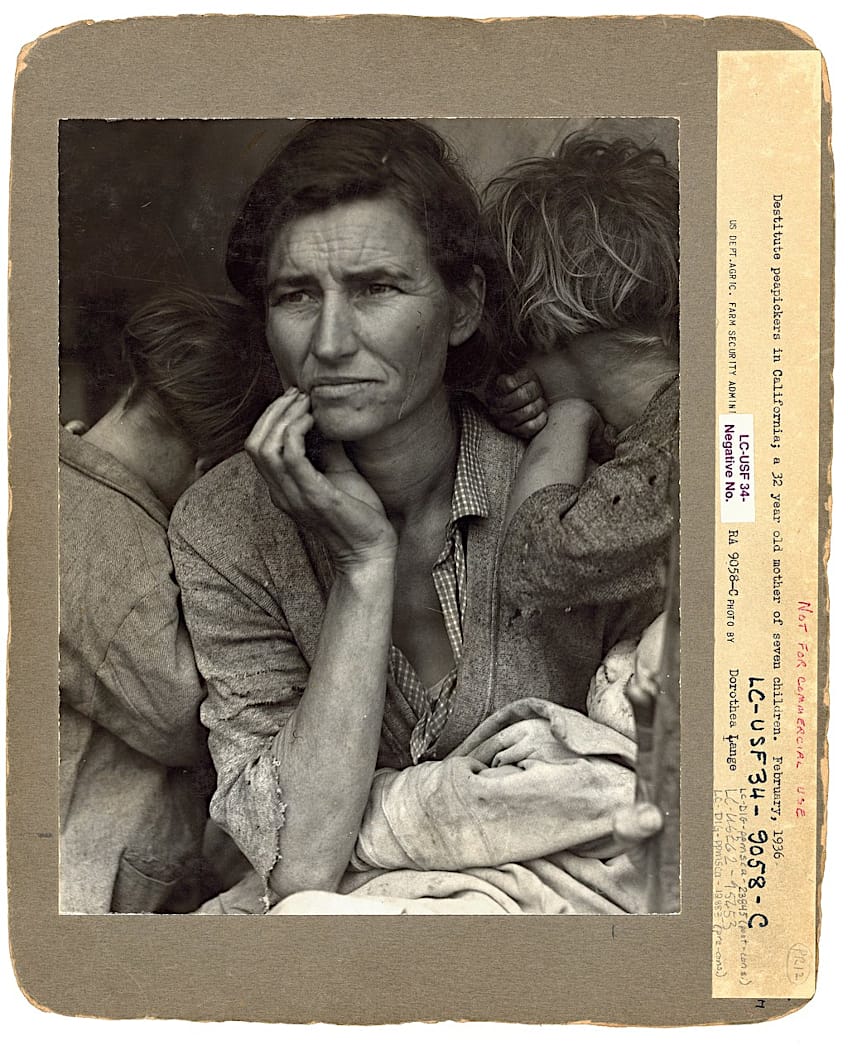

Modern Photography (1910 – 1960)

A momentous visual change was brought about by the birth of Modern Photography as well as in the production of photography and how it was used and appreciated. The shift in Modern Photography from early photography is marked by a deviation from traditional art limits, broadening what constituted art and which subject matter was acceptable in the production of it.

Modern photography became integrated into modern art movements such as Surrealism and Dada, providing a new medium for expression.

| Modern Photography Works | |||||

| Title | Artist | Date | Dimensions (cm) | Medium | Current Location |

| Blind | Paul Strand (1890-1976) | 1916 | 34 x 25.7 | Platinum print | The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, United States |

| Workers Parade | Tina Modotti (1896-1942) | 1926 | 21.5 x 18.6 | Gelatin silver print | The Museum of Modern Art, New York, United States |

| Noire et blanche | Man Ray (1890-1976) | 1926 | 17.1 x 22.5 | Gelatin silver print | The Museum of Modern Art, New York, United States |

| Migrant Mother, Nipomo, California | Dorothea Lange (1895-1965) | 1936 | 28.3 x 21.8 | Gelatin silver print | The Museum of Modern Art, New York, United States |

| Uruapan 11 | Aaron Siskind (1903-1991) | 1955 | 36.6 x 49.5 | Silver gelatin print | The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, United States |

Arts & Crafts Movement (1860 – 1920)

The Arts & Crafts movement reacted to the Industrial Revolution and the increasingly mechanized way of living. However, as those part of the movement in the United Kingdom had a negative attitude towards industrialization, those in America leaned more towards embracing it.

The Arts & Crafts movement sought a more fulfilling way of living that was simple and beautiful, believing that art could transform society through the connection forged between the artist and handcraft.

The movement is known for its stressing the importance of functionality in design and for using materials of high quality, its artists being linked with decorative arts and architecture rather than sculpture and painting of “high” art. Their style varied but they were most greatly influenced by imagery found in nature as well as medieval art.

| Works from the Arts & Crafts Movement | |||||

| Title | Artist | Date | Dimensions (cm) | Medium | Current Location |

| Tulip and Rose | Morris & Co. (1861-1939) | 1876 | 83.2 x 41.7 | Wool curtain, triple-cloth weave | Cooper-Hewitt Museum, New York, United States |

| Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales | William Morris (1834-1896) | 1896 | N/A | Engraved, woodcut prints, paper, and ink | The British Library – Boston Spa, Wetherby, West Yorkshire, United Kingdom |

| Sideboard | Charles F. A. Voysey (1857-1941) | 1897 | 150.81 x 137.16 x 62.55 | Oak and brass | Los Angeles County Museum of Art, United States |

| The Fairy | Duilio Cambellotti (1876-1960) | 1917 | Diameter: 64 | Stained Glass | Musei di Villa Torlonia, Rome, Italy |

| Vase | Sarah Agnes Estelle Irvine (1887-1970), and Joseph Meyer ([s.a]) | 1922 | N/A | Glazed Ceramic | The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, United States |

Art Nouveau (1890 – 1905)

Art Nouveau included creators from various areas, such as architecture, and the graphic and decorative arts from all over Europe and elsewhere in the world. Therefore, it has different names, such as Jugendstil (in German) or the Glasgow Style. Art Nouveau, meaning “new art”, endeavored to transform design to adapt to a more modern world and leave behind the previously favored historical designs.

The movement challenged the traditional hierarchy in the art world, aiming to eliminate the gap between craft and decorative arts and painting and sculpture considered as “high” art. Linear contours were important in the style of Art Nouveau, more so than color.

Artists were inspired by forms found in nature, flattening and abstracting subjects to create elegant flowing patterns and shapes, many with arches and curves that became signature to the style.

| Art Nouveau Artworks | |||||

| Title | Artist | Date | Dimensions (cm) | Medium | Current Location |

| Wren’s City Churches | Arthur Heygate Mackmurdo (1851-1942) | 1883 | 29 x 23 | Woodcut on handmade Paper | Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas, Texas, United States |

| La Goulue at the Moulin Rouge | Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864-1901) | 1891 | 168 x 118.7 | Lithograph | The Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, United States |

| The Dancer’s Reward | Aubrey Beardsley (1872-1898) | 1894 | 34 x 27 | Block Print | Private collection |

| Rêverie | Alphonse Mucha (1860-1939) | 1898 | 72.7 x 55.2 | Color lithograph | Private collection |

| The Kiss | Gustav Klimt (1862-1918) | 1907 – 1908 | 180 x 180 cm | Oil and gold leaf on canvas | Österreichische Galerie Belvedere, Vienna, Austria |

Art Deco (1900 – 1945)

Art Deco was a modern style that spanned across painting, architecture, sculpture, and decorative arts and, like Art Nouveau, sought to combine functional objects with an artistic aesthetic. However, it differed from Art Nouveau and the Arts & Crafts Movement in that it did not focus on handmade objects that were original but made aesthetically pleasing items that were often machine produced and available to everyone.

Art Deco originated in Paris and spread to the rest of Europe, America;, and then the world its style was characterized by geometric, sleek, symmetrical, stylized, and elegant forms. Visual art pieces included both mass-produced and extravagant works that were individually made.

| Art Deco Artworks | |||||

| Title | Artist | Date | Dimensions (cm) | Medium | Current Location |

| Le miroir rouge / The Red Mirror | Georges Lepape (1887-1971) | 1914 | 27.5 x 22 | Pochoir with metallic paint | Sylvan Cole Gallery, Sitges, Barcelona, Spain |

| Victoire | René Lalique (1860-1945) | 1928 | 23 x 24.6 | Glass, metal and wood | Corning Museum of Glass, New York United States |

| Green turban | Tamara Lempicka (1898-1980)

| 1929 | 41 x 33 | Oil on cardboard | Private collection |

| Tipsy | Kobayakawa Kiyoshi (1897-1948) | 1930 | 43 x 27 | Woodblock print | Honolulu Museum of Art, Honolulu, Hawaii |

| Rythme | Sonia Delaunay (1885-1978) | 1938 | 182 x 149 | Oil on canvas | Collection of Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, Paris, France |

| Nude with Calla Lilies | Diego Rivera (1886-1957) | 1944 | 157 x 124 | Oil on panel | Private collection |

Modern Art (c. 1860 – c. 1970)

Modernism was a movement that took over the Western world during the 19th and 20th centuries and was influenced by modern progress and industrial life. Various political and social agendas also drove Modernism, which was often utopian and idealistic in the strive for progress.

Modernism and Modern art are both terms that represent a departure from traditional art styles and conservative values with artists from around the world individually and collectively pursuing new ways of making art and experimenting with form.

Although modern art properly began with Realism around 1850, art styles and approaches to art were determined and revised throughout the 20th century with artists looking for new ways of representing the times in which they lived and developing styles that were original. Below we list some of the most influential Modern art movements and notable artworks.

Impressionism (1862 – 1892)